Print or print to save this page as a PDF.

Download the Supplemental PDF files.

≻ 3.9 Dąbrowski’s Approach to Testing: An Introduction. (DOWNLOAD PDF).

≻ 3.13 Master References. (DOWNLOAD PDF).

Other relevant links:

≻ 9.3 Dr. Dąbrowski and Dr. Piechowski.

≻ 12. A brief historical overview of sensitivity and overexcitability.

⚁ 3.1 Preparatory Material (⚀ 1 Introduction to TPD.).

⚁ 3.2 Introduction to this learning guide.

⚁ 3.3 50 Key Points.

⚁ 3.4 Major Constructs.

⚁ 3.5 Unique Terms.

⚁ 3.6 Dąbrowski’s Glossary.

⚁ 3.7 Tillier’s Initial Presentation of the Theory.

⚁ 3.8 Tillier’s Advanced Presentation of the Theory.

⚁ 3.9 Dąbrowski’s Approach to Testing: An Introduction [PDF].

⚁ 3.10 Films of Dąbrowski. [LINK]

⚁ 3.11 An Excellent Overview Article by Tylikowska, (2000).

⚁ 3.12 Biography.

⚁ 3.13 Master References. [PDF]

⚁ 3.1 Preparatory Material (⚀ 1 Introduction to TPD.).

⚁ 3.2 Introduction to this learning guide.

⚁ 3.3 50 Key Points.

⚁ 3.4 Major Constructs.

⚂ 3.4.1 Introduction.

⚂ 3.4.2 Positive disintegration.

⚂ 3.4.3 Psychoneuroses.

⚂ 3.4.4 Multilevelness.

⚂ 3.4.5 Developmental potential.

⚂ 3.4.6 The three factors.

⚂ 3.4.7 Essentialism/existentialism.

⚂ 3.4.8 Authenticity/personality.

⚂ 3.4.9 Dynamisms.

⚂ 3.4.10 Instincts.

⚂ 3.4.11 Inner psychic milieu / disposing and directing center.

⚂ 3.4.12 Subject-object.

⚂ 3.4.13 Overexcitability.

⚂ 3.4.14 A brief historical overview of sensitivity and overexcitability.

⚁ 3.5 Unique Terms.

⚂ 3.5.1 Introduction.

⚂ 3.5.2 Adjustment – An articulated approach.

⚂ 3.5.3 Ambitendencies and ambivalences.

⚂ 3.5.4 Development.

⚂ 3.5.5 Education and self-education.

⚂ 3.5.6 Emotions (a.k.a. values) direct development.

⚂ 3.5.7 Hierarchization and value development.

⚂ 3.5.8 Mental health and mental illness.

⚂ 3.5.9 Psychopathy/psychopath.

⚂ 3.5.10 Psychotherapy and autopsychotherapy.

⚂ 3.5.11 Unilevel disintegration.

⚁ 3.6 Dąbrowski’s Glossary.

⚁ 3.7 Tillier’s Initial Presentation of the Theory.

⚂ 3.7.1 Introduction and Context.

⚂ 3.7.2 What is development?

⚂ 3.7.3 Marie Jahoda.

⚂ 3.7.4 Multilevel and Multidimensional Approach.

⚂ 3.7.5 Dąbrowski’s 5 Levels.

⚂ 3.7.6 Disintegration.

⚂ 3.7.7 Developmental Potential.

⚂ 3.7.8 Intuition.

⚂ 3.7.9 Emotion and Values in Development.

⚂ 3.7.10 Applications of the TPD.

⚂ 3.7.11 Applications in Education.

⚂ 3.7.12 Applications in Gifted Education.

⚂ 3.7.13 Current and Future Issues.

⚂ 3.7.14 Conclusion of Tillier’s initial presentation of the theory.

⚁ 3.8 Tillier’s Advanced Presentation of the Theory.

⚂ 3.8.1 Introduction and Context.

⚂ 3.8.2 Dąbrowski and Philosophy.

⚂ 3.8.3 Creativity and the Theory of Positive Disintegration.

⚂ 3.8.4 Dąbrowski and Positive Psychology.

⚂ 3.8.5 Dąbrowski and Posttraumatic Growth.

⚂ 3.8.6 Dąbrowski and Maslow.

⚂ 3.8.7 Dąbrowski and John Hughlings Jackson.

⚂ 3.8.8 Conclusion of Tillier’s second presentation of the theory.

⚁ 3.9 Dąbrowski’s Approach to Testing: An Introduction [PDF].

⚁ 3.10 Films of Dąbrowski.

⚁ 3.11 An Excellent Overview Article by Tylikowska, (2000).

⚂ 3.11.1 Introduction.

⚂ 3.11.2 Primary integration.

⚂ 3.11.3 One-level disintegration.

⚂ 3.11.4 Multilevel spontaneous disintegration.

⚂ 3.11.5 Organized multi-level disintegration.

⚂ 3.11.6 Secondary integration.

⚂ 3.11.7 Reference.

⚁ 3.12 Biography.

⚁ 3.13 Master References:

“Everyone thinks it’s a full-time job.

Wake up a hero.

Brush your teeth a

hero.

Go to work a hero.

Not true.

Over a lifetime, there are only four or five moments that really matter.

Moments when you’re offered a choice – to make a sacrifice, conquer a flaw, save a friend, spare an enemy.

In these moments, everything else falls away.”

Colossus.

(Miller, 2016).

This page serves as a guide to self-education in the theory of positive disintegration. It is meant to be used alongside Dąbrowski’s original materials.

≻ This page is not intended to “teach the theory;” rather, it serves as a guide to help you explore the ideas outlined in the original materials.

≻ The page has two sections. The first section provides a basic introduction and overview, while the second section delves into the fundamental principles and applications of the theory.

As discussed at one of the conferences, I do not believe in “experts.” They often express confidence but lack genuine knowledge. Instead, I advocate for an archaeological model where you, the learner, are empowered to dig deeply into the topic independently. This approach allows you to gain an overview of the theory at your own pace and then delve into the details as you progress.

The page has two sections. The first section provides a basic introduction and overview, while the second section delves into the fundamental principles and applications of the theory.

I hope you enjoy the material, Bill.

⚂ As a youth, Dąbrowski was affected by his experience of the aftermath of battle in World War I.

⚂ When his best friend committed suicide during college in the 1920s, Dąbrowski decided to study mental health.

⚂ The theory’s basic ideas begin to appear in Dąbrowski’s 1929 thesis and developed over his lifetime.

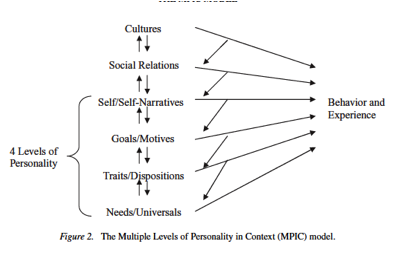

⚂ The theory integrates ideas from traditional philosophy, neurology, psychology, and psychiatry, and introduces several new constructs and terms.

⚂ Dąbrowski observed that people who self-harm often show overexcitability, psychic disintegration, and psychoneuroses (1934, 1937).

⚂ Dąbrowski was caught in World War II and endured several incarcerations in the German prison system and later, he and his wife were imprisoned again in Stalin-controlled Poland where Dąbrowski was tortured.

⚂ Dąbrowski said he could find no theory of psychology that could adequately explain both the lowest and depraved behavior, as well as the most heroic and highest acts, he had witnessed.

⚂ Dąbrowski studied biographies of people who displayed exemplary personality development.

⚂ Dąbrowski’s goal was to write a “general theory of development” explaining the factors and processes involved in what he perceived to be advanced personality development.

⚂ The theory is initially challenging to understand because it has many interrelated constructs and contains a number of unique terms that Dąbrowski developed.

⚂ Rejecting the idea that higher developments are built upon lower ones, Dąbrowski believed that advanced development required the break-down of lower psychological structures through a process he called positive disintegration.

≻ Development is represented by new partial integrations at higher levels, ultimately culminating in a ‘secondary integration.’

⚂ Based upon his observations, Dąbrowski formulated a concept called developmental potential describing a constellation of genetic factors that appear to be necessary to promote advanced development.

⚂ According to Dąbrowski, only a limited number of individuals display sufficient developmental potential for advanced development to occur.

⚂ Dąbrowski emphasized three key components of developmental potential; special talents and abilities (e.g. high intelligence, athletic ability, artistic or musical talent), third factor (a strong internal drive to express oneself through making autonomous choices) and overexcitability.

⚂ Overexcitability is a characteristic of the nervous system involving higher than average sensitivity to stimuli (a lower threshold to stimuli) and a higher than average response to stimuli.

⚂ Dąbrowski described five main types of overexcitability: psychomotor, sensual, intellectual, imaginational and emotional, and emphasized that the latter three are critical to development and in particular, that emotional overexcitability drives and guides higher development.

⚂ Dąbrowski believed that life choices must be made with an awareness of one’s emotional reactions to a situation and not solely using a rational and intellectual basis.

⚂ Strong developmental potential is necessary, but not sufficient, for advanced development.

⚂ In development, there is a critical qualitative transition from perceiving reality based upon unilevel experience to a multilevel view of life.

⚂ Unilevel experience tends to be uniform with little to distinguish alternatives from one another and one’s actions tend to be rote and based upon automatic stimulus/response reactions where conflicts arise between different but equivalent choices.

≻ Choices are guided externally – by social expectations and mores.

⚂ Multilevelness involves a perception of reality based upon an awareness of the broad spectrum of life; from the lowest, most primitive aspects, to the highest, and most developed.

≻ Choices are made based upon an internalized value structure.

⚂ Multilevelness involves a hierarchical view of reality that creates conflicts between higher possibilities in comparison to lower realities and alternatives: one comes to the fork between the low road and the high road and one clearly sees these two pathways as qualitatively different.

⚂ Multilevelness becomes critical in making life choices as higher versus lower aspects of situations become clear to us.

≻ If we see this distinction and subsequently choose the lower road, feelings of guilt, disappointment, self doubt, failure, and shame often result.

≻ These feelings subsequently influence one’s future decision-making toward the higher path.

⚂ A key component of personality is the development of individualized values (the hierarchy of values) and a vision of “higher possibilities,” culminating in the idealization of the kind of person one wishes to become; a feature Dąbrowski called personality ideal.

⚂ Development is an individual challenge to overcome one’s life “as it is” through inhibition and transformation of lower features and to develop and create one’s own unique character and one’s life “as it ought to be.”

⚂ Dąbrowski differentiated three primary groups of people, first, a group of individuals who display unilevel development.

≻ These individuals are primarily influenced by socialization and comprise some 65% of the population; a group defined by Dąbrowski as primary integration.

⚂ A second group of individuals are characterized by various forms and degrees of positive disintegration, indicating that they are moving through the developmental process.

⚂ A third group of individuals represent the ideal of development, defined by Dąbrowski as secondary integration.

⚂ Positive disintegration involves psychoneuroses; strong anxieties and depressions that signal the breakdown of lower structures and that are a necessary component of development.

⚂ Dąbrowski believed psychological symptoms must be evaluated and interpreted in the context of an individual’s history and their level of developmental potential.

⚂ Traditional approaches to mental health view overexcitability and psychoneuroses as symptoms that must be eliminated and no traditional approach helps the individual with strong developmental potential to learn to cope with life: living as a “square peg in a round world.”

⚂ Dąbrowski developed a multilevel and multidimensional approach to diagnosis which emphasized collaboration with the client to determine the developmental context and meaning of their symptoms and life situation.

⚂ Based upon one’s diagnosis, a client with significant developmental potential and positive disintegration would be suitable for Dąbrowski’s approach to therapy: autopsychotherapy.

⚂ Autopsychotherapy emphasizes the need for an individual to develop insight into their own characteristics and to understand their behavior in a developmental context.

⚂ Using self-understanding and autoeducation, one can learn to self-manage one’s strong feelings and, eventually, to actively direct one’s development toward one’s personality ideal.

⚂ Autoeducation is a key component of development, emphasizing the unique educational needs of each individual.

≻ These go beyond simply learning academic material, this is what YOU need to know to live a successful life.

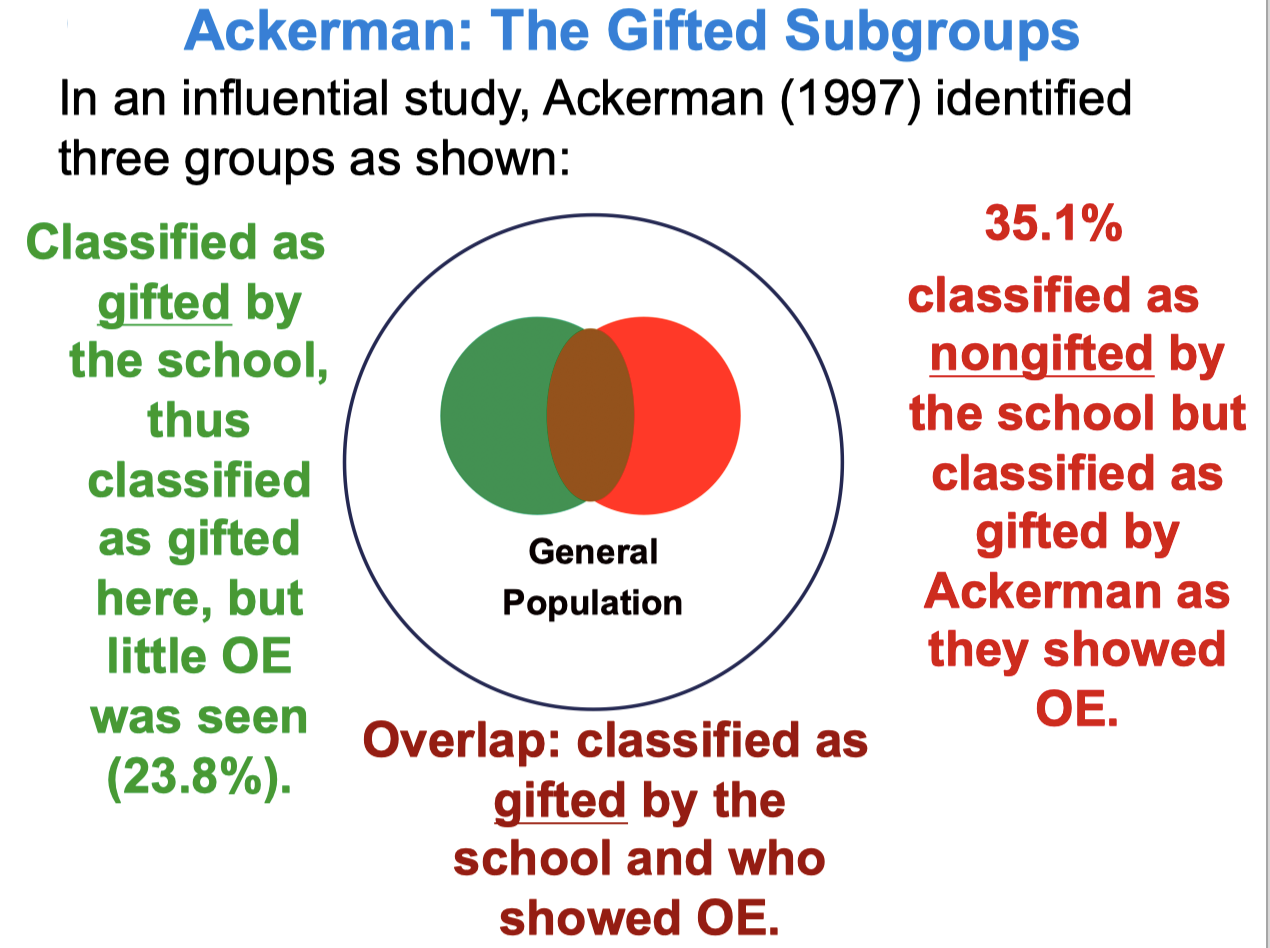

⚂ One of Dąbrowski’s research studies examined gifted children and found that they exhibited high levels of developmental potential and psychoneuroses, leading Dąbrowski to hypothesize that gifted children may be predisposed to experience positive disintegration.

⚂ Some 40 years of research examining overexcitability in gifted students has yielded somewhat equivocal results.

⚂ Research has demonstrated that gifted individuals are more likely than those not identified as gifted to show signs of only one of the five overexcitabilities: intellectual overexcitability.

⚂ Research done to date has not supported the idea that gifted students are universally predisposed to advanced development as described in Dąbrowski’s theory.

⚂ Dąbrowski formulated five levels describing a sequence of development spanning from primary integration, through three levels of disintegration and culminating in a secondary integration.

⚃ Primary integration is a cohesive psychological structure controlled by one’s primitive drives and the forces of socialization.

≻ According to this theory, no true autonomy or individual personality exists.

≻ Little internal conflict arises as one “gets along by going along.”

⚃ In Dąbrowski’s vision of development, the initial breakdown of primary integration involves unilevel conflicts; conflicts that begin to arise between alternatives that are essentially equivalent, and thus the name of the second level: unilevel disintegration.

⚃ As there is no vertical aspect to unilevel conflicts, there is no developmental solution available and one must either return to primary integration or move ahead to multilevelness.

⚃ The third level, spontaneous multilevel disintegration, involves the beginning of multilevelness, signified when an individual spontaneously experiences conflicts between lower versus higher aspects of their experience.

⚃ The fourth level is a continuation of multilevelness but, by now, the individual has some control over their development and they begin to direct their disintegrations – hence the name directed multilevel disintegration.

⚄ At the fourth level, one develops an idealized sense of oneself and the kind of person one wants to become, and alternately, one also develops a sense of the aspects of oneself that one must overcome, inhibit or transform.

≻ The individual comes to play a conscious and volitional role in directing the developmental process.

⚃ With higher development, internal conflicts begin to subside as the individual’s personality ideal is slowly realized through the ongoing choices one makes in life.

⚃ Level V, secondary integration, becomes a lifelong continuation of the goal of pursuing one’s personality ideal and striving for self-perfection.

≻ One’s actions are now in harmony with one’s values and any sense of disintegration has passed.

⚄ One has a sense of internal harmony however, sharp external conflicts with society may arise as multilevelness guides the individual in pursuit of trying to make the world a better place.

⚂ 3.4.1 Introduction: The dynamics of concepts (Dąbrowski, 1973).

⚃ Dąbrowski presented a theory of personality development rich in new concepts.

≻ Not only did Dąbrowski present new concepts but he called for a new way to look at concepts altogether.

≻ Dąbrowski realized that traditional conceptual descriptions of psychological phenomena could not adequately capture a developmental and multilevel perspective.

≻ Psychological attributes that vary widely with development and across levels require flexible and “dynamic” concepts that can adequately describe these differences.

⚃ Concepts versus constructs.

⚄ Simply put, as I understand it, concepts and constructs are both abstractions.

≻ Concepts describe real objects or factual objects, that is to say, the abstract concept of an aircraft is based on the existence of, examination of, and observation of, a real object in the world – a particular aircraft.

≻ On the other hand, constructs are postulated attributes, usually based upon observations. For example, an aircraft has a center of gravity; the center of gravity is a construct.

≻ It does not apply to a physical object in the world. In psychology, constructs are generally taken to be postulated attributes of individuals inferred from their behavior.

≻ For example, IQ is a construct inferred from an individual’s performance on a test.

≻ IQ does not exist in the real world and is not directly observable the way an aircraft would be.

≻ The construct of IQ is a hypothesized attribute or quality of an individual that is not directly observable (it is literally made up or constructed by the psychologist).

≻ IQ is inferred from observation (performance on tests) to account for differences observed between individuals.

≻ There is an ongoing call for precision when discussing concepts and constructs in psychology.

≻ Dąbrowski used the term concepts however, the ideas he described would more properly be termed constructs today.

≻ For more information, see Slaney and Racine (2013a, 2013b).

⚄ It is helpful to have a brief general orientation to constructs before we look at the novel approach that Dąbrowski proposed.

⚄ One major application of constructs considers how human beings use concepts psychologically.

≻ Machery (2009) describes this approach:

≻≻ The properties of concepts explain how people categorize, reason inductively, draw analogies, or understand sentences. The properties of Jamie’s concept of dog explain why she categorizes dogs the way she does, why she draws analogies about dogs the way she does, and so on. Similarly, the general properties of concepts explain the properties that the higher cognitive competences possess, whatever concept is involved. The general properties of concepts explain the properties of our categorization decisions, whether we categorize something as a dog, as a table, as water, or as a birthday party” (p. 20).

⚄ This context of concepts has received considerable attention in the psychological literature (Machery, 2009, 2007; Özdemir and Clark, 2007; Szostak, 2011).

≻ Although several approaches to the theory of concepts have been proposed, there appears to be no general consensus in psychology in terms of a preferred theory (Machery, 2009).

≻ Machery (2009) offers a comprehensive treatment of the topic and pessimistically concludes that psychology should avoid using concepts altogether.

≻ This controversial conclusion is fully explored in Machery (2010) and the discussion that follows.

⚃ Concepts in psychological research

⚄ Concepts as constructs describing psychological variables are the cornerstone of psychological theory building and research.

≻ Concepts are largely metaphorical descriptions of the phenomenon under consideration.

≻ In this context it is critical that constructs represent an accurate and valid description of reality.

≻ Thus, construct validity is a critical aspect of using concepts in psychology.

⚃ Construct validity

⚄ The idea of construct validity has been fundamental in psychology since its introduction in 1955 by Cronbach and Meehl.

≻ Construct validity is commonly misunderstood as an indication of the relative validity of a test or questionnaire.

≻ In reality, construct validity is an indicator of the clarity and appropriateness of a given concept.

⚃ Cronbach and Meehl (1955), explain:

≻ A construct is some postulated attribute of people, assumed to be reflected in test performance. In test validation the attribute about which we make statements in interpreting a test is a construct. We expect a person at any time to possess or not possess a qualitative attribute (amnesia) or structure, or to possess some degree of a quantitative attribute (cheerfulness). A construct has certain associated meanings carried in statements of this general character: Persons who possess this attribute will, in situation X, act in manner Y (with a stated probability). (pp. 283-284)

⚃ Cronbach and Meehl (1955) go on:

⚄ To specify the interpretation, the writer must state what construct he has in mind, and what meaning he gives to that construct. For a construct which has a short history and has built up few connotations, it will be fairly easy to indicate the presumed properties of the construct, i.e., the nomologicals in which it appears. For a construct with a longer history, a summary of properties and references to previous theoretical discussions may be appropriate. It is especially critical to distinguish proposed interpretations from other meanings previously given the same construct. The validator faces no small task; he must somehow communicate a theory to his reader. (p. 297)

⚄ Discussion of construct validity continues in the psychological literature today.

≻ “The ‘construct’ has become psychology’s unit of analysis and construct validation its modus operandi” (Slaney, 2012, p. 291).

≻ Slaney (2012) elaborates that in construct validity, it is not the test that is under scrutiny, it is the trait or quality underlying the test that is of critical importance.

≻ She quotes the 1954 “Technical Recommendations” paper of the American Psychological Association: “in construct validity it is ‘the trait or quality underlying the test [emphasis added] that is of central importance, rather than either the test behavior or the scores on the criteria’” (Slaney, 2012, p. 292).

⚄ “The theory underlying both the test and the construct may be conceived as an ‘interlocking system of laws’ which is known as a ‘nomological network’” (Slaney, 2012, p. 292). “This network gives constructs whatever meaning they have at a given stage of science” (Slaney, 2012, p. 293).

⚄ There is a wide latitude of approaches when it comes to constructs.

≻ “One easily and often comes across references to constructs being ‘unobservable attributes,’ ‘latent traits,’ or other entities or processes which are hypothesized to ‘underlie,’ ‘mediate,’ ‘account for,’ and ‘explain’ observable behaviors” (Slaney, 2012, p. 293).

⚃ Concepts as descriptive metaphors

⚄ In its original usage, a metaphor referred to the act of giving something a name that refers to something else.

≻ For example, “he had the eyes of a hawk.” In this case, the speaker is drawing an inference that the acuity of the individual’s vision is equivalent to that of a hawk.

≻ In the same way, psychologists use concepts to refer to psychological structures.

≻ For example, we refer to “levels of personality” and we understand this to be a conceptual metaphor and not intended to describe some actual physical structure within the brain.

≻ Various concepts (for example, structures, levels, drives, centers, etc.) act as heuristic devices to help us imagine how a given phenomenon, in this case personality, operates and develops.

≻ In our concepts, we are striving to accurately describe and portray an internal mental state or process and thus achieve construct validity: we want our theory and concepts to accurately portray and capture the characteristics of the phenomena we are describing.

⚄ “Theories, and the concepts and metaphors that they may contain are essentially the researchers instruments or tools with which he or she relates to the given object(s) in reality that is (are) under study” (Zittoun, Gillespie, Cornish, and Psaltis, 2007).

⚄ Reflecting the approach to construct validity above, the concepts and metaphors we choose have to be appropriate to convey our theory and intended meaning.

≻ This posed a significant problem for Dąbrowski as he saw that the phenomena he was trying to describe were not static, rather, these phenomena often were highly dynamic and changed dramatically over time and with development.

≻ As well, the static and unilevel concepts commonly used in psychology were unable to capture the complexity and dynamic nature of phenomenon when dimensions and levels of development were considered.

≻ The same phenomenon seen at different levels of development often demands quite different descriptions, necessitating Dąbrowski to create new and richer concepts to accurately capture the “changeability of concepts.”

⚃ Dąbrowski (1973) stated:

The terminology of contemporary psychology is extremely complicated and confusing. It is notorious that one and the same term refers to distinctly different phenomena, while phenomena of the same kind are referred to by different terms. Hence the need, even the necessity of a revision of many crucial concepts, of new distinctions and of an examination of concepts from a dynamic, developmental point of view; that is to say, from the viewpoint which will acknowledge fundamental transformations of the content of mental processes and related concepts… Such a dynamic point of view is characteristic of positive disintegration and also of some semantic studies. Contrary to the tendencies to precision and reductionism of the many meanings of a given concept to just one meaning, this new point of view represents the tendency to disintegrate and even break up many concepts into a number of clearly differentiated concepts. It is due to the need to find an adequate new conceptual expression for new insights into reality which cannot be adequately expressed by means of former concepts and distinctions. This process of disintegration of concepts is frequently followed by a later process of an opposite nature which combines and integrates formerly separated conceptual units which are strictly elaborated. Growing knowledge of reality may generate the need to reunite various threads of thought in a secondary integration of concepts at a higher level which expresses new insights. As examples of this secondary integrating process we may mention the concept of higher emotions (attitudes) which combines intellectual, emotional and volitional components, as well as, existentio-essentialist and empirico-normative compounds discussed in separate chapters of this book. (pp. vii-viii)

⚄ “The changeability of concepts and terms depends on the psychic transformation of man and expresses the developmental transformation of human individuals, the growth of their autonomy and authenticity, of their inner psychic milieu and of their growing richness of life experiences” (Dąbrowski, 1973, p. viii).

⚄ “Our attempts to give a theoretical account of specifically human forces will never succeed if we continue to disregard the dynamic, developmental and multilevel nature of human ontogeny. The distinction of higher and lower instincts, as well as, the distinctions of higher and lower levels within one instinct and its ontogenetic transformations seem to be indispensable to achieve an adequate understanding and theoretical description of mental development” (Dąbrowski, 1973, p. xi).

⚄ “The growing conceptual complexity and substantial change in the use of concepts is characteristic of every process of growing insight into reality. It is a positive phenomenon which attests to the dynamic and turbulent ‘life’ of concepts” (Dąbrowski, 1973, pp. xi-xii).

⚄ “The concept of authenticity raises the same kind of problems. If its use is to be of any value, it is necessary to distinguish authentic existence emanating from autonomous mental development, from the growth and richness of the inner psychic milieu, from positive disintegration and destruction of the lower, primitive mental structure, on the one hand, and, the so-called ‘authentic’ externalization of brutal, thoughtless, elementary drives, on the other hand” (Dąbrowski, 1973, p. xiii).

⚄ “A ‘dynamization’ of concepts seems to be particularly important in developmental and educational psychology, in the study of interpersonal relations and in psychopathology, especially in the theory of psychoneuroses. The results of this process of dynamization of concepts will more and more express the close association and interconnection of intellectual and emotional functions. The new meanings of concepts should allow a much more incisive analysis of the understanding of oneself, of other individual and human groups” (Dąbrowski, 1973, p. xiii).

⚄ “Let us restate our view in a brief summary. Many-sided and authentic development of man implies the formation of an adequate system of concepts and terms which would correspond to the new higher stages of this development. Consequently, those concepts which are not adequate at new stages of development must be disintegrated and transformed. New, and richer concepts must be worked out in order to adequately express new cognitive and affective qualities of a growing personality. Hence, the development of concepts and terms expresses the development of man, particularly his accelerated and autonomic growth. New qualities and new experiences arising in the process of mental development manifest the various symptoms of disintegration through which they become independent, grow in richness, and reveal new creative forms…. This process of transformation of concepts and terms in their intellectual and experiential aspects can be called ‘the drama of the life and development of concepts’” (Dąbrowski, 1973, pp. xiv-xv).

⚃ Research in general

⚄ It is helpful to put this discussion in the context of a larger, ongoing debate over the fundamental issues related to psychological measurement.

≻ Maslow (1966) was disappointed that psychology became obsessed with methodology and significance at the expense of the study of meaningful phenomena, an obsession he called methodolatry.

≻ Cohen (1994, p. 997) said that null hypothesis significance testing “had not only failed to support the advance of psychology as a science but also has seriously impeded it.” More recently, Borsboom (2005, p. 2) declared that “after a century of theory and research on psychological test scores, for most test scores we still have no idea whether they really measure something, or are no more than relatively arbitrary summations of item responses.” This view was further emphasized by Markus and Borsboom (2011, p. 453): “notwithstanding the fact that common practices in psychology take for granted the idea that psychological attributes are measurable, and in fact are measured by commonly used tests, skepticism about the validity of this assumption has been an undercurrent during the entire history of psychology.”

⚃ It’s not about how you want it to be

⚄ Lambdin (2012) presented a review of current psychological research, referring to the state of affairs as “statistical shamanism.” In this important article, he quoted Stanislav Andreski, suggesting that many in the social sciences end up making claims because they want their opinions to become reality, not because their claims are based upon corroborated and diverse evidence.

⚄ Lambdin (2012) states:

⚅ Many social scientists make the claims they do, Andreski states, not because they have corroborated, diverse evidence supporting them as accurate descriptors of reality, but rather because they desire their opinions to become reality. This, Andreski argues, is shamanistic, not scientific (p. 67).

⚃ Andreski (1972/1974) a Polish sociologist, makes his case clear:

≻ More than that of his colleagues in the natural sciences, the position of an ‘expert’ in the study of human behavior resembles that of the sorcerer who can make the crops come up or the rain fall by uttering an incantation. And because the facts with which he deals are seldom verifiable, his customers are able to demand to be told what they like to hear, and will punish the uncooperative soothsayer who insists on saying what they would rather not know-as the princes used to punish the court physicians for failing to cure them. (p. 24)

⚃ Andreski (1972/1974) goes on:

⚄ “[In psychology] significant discoveries are rare, and must remain exceedingly approximate and tentative. Most of the practitioners, however, do not like to admit this and prefer to pretend that they speak with the authority of an exact science, which is not merely theoretical but also applied” (p. 25).

⚃ We often see examples of the application of “strict science” to psychology. For example, from the literature on positive psychology, we find the following (some mumbo jumbo is also helpful in presenting such findings):

≻ Fredrickson and Losada, (2005) define flourishing using the positivity/negativity ratio (P/N): the ratio of good thoughts/positive feedback (e.g. “that is a good idea”;) vs. negative thoughts/negative feedback (e.g. “this is not what I expected; I am disappointed”).

⚄ Mathematically, then, a positivity ratio of about 2.9 bifurcates the complex dynamics of flourishing from the limit cycle of languishing. We call this dividing line the Losada line. From a psychological standpoint, this ratio may seem absurdly precise. Yet we underscore that this bifurcation point is a mathematically derived theoretical ideal. Empirical observations made at various levels of measurement precision can test this prediction” (Fredrickson & Losada, 2005, p. 683).

⚄ The Losada line establishes the minimum level at which a “complexor” is reached and is equal to a P/N of 2.9013. “Our discovery of the critical 2.9013 positivity ratio may represent a breakthrough” (Fredrickson & Losada, 2005, p. 685).

⚃ In Dąbrowski’s words:

⚄ Dąbrowski also commented on the issues of research in psychology. “The present work consists of an attempt to reveal and protect the plasticity and richness, observable in the dynamic transformations of concepts, against the danger of ossification, unilevelness and sterility arising from a one-sided stress on the requirements of verifiability, precision and statistical elaboration” (Dąbrowski, 1973, p. xiii).

≻ This presents a logical contradiction to the careful reader.

≻≻ Here, in 1973, Dąbrowski is cautious of over-precision and a unilevel approach to measurement.

≻≻ Yet, the 1977 volumes present a great deal of just such research. Why?

≻≻ In the late 1960’s, the Canada Council made available funding for empirical research projects.

≻≻ Piechowski had come into Dąbrowski’s group from a background in biology and believed that he could operationalize much of Dąbrowski’s theory.

≻≻ He worked tirelessly on an extensive research project that culminated in much of the empirical material presented in the 1977 books.

≻≻ From my firsthand understanding from Dąbrowski, he appreciated this effort but did not wholeheartedly endorse it.

⚃ A comment on positive versus negative

⚄ This review focuses on a positive/developmental emphasis.

≻ It should be noted that many of these concepts have positive and negative formulations.

≻ For example, the outcome of disintegration can be either positive or negative depending upon several factors, primarily, one’s initial level of developmental potential.

≻ Authenticity can be positive or negative.

≻ Development implies a positive authenticity; an individual’s personality ideal will represent higher and nobler human values.

≻ On the other hand, an individual at a very low developmental level may “be true to him or herself” and authentically express very low level instincts or egocentric drives.

≻ When looking at these concepts it should be remembered that this treatment only considers the developmental or positive aspects.

⚂ 3.4.2 Positive disintegration:

⚃ Positive disintegration is the core concept of the Theory of Positive Disintegration. What does it mean?

⚃ “Dąbrowski refers to his view of personality development as the theory of positive disintegration. He defines disintegration as disharmony within the individual and in his adaptation to the external environment. Anxiety, psychoneurosis, and psychosis are symptoms of disintegration. In general, disintegration refers to involution, psychopathology, and retrogression to a lower level of psychic functioning. Integration is the opposite: evolution, psychic health, and adequate adaptation, both within the self and to the environment. Dąbrowski postulates a developmental instinct: that is, a tendency of man to evolve from lower to higher levels of personality. He regards personality as primarily developing through dissatisfaction with, and fragmentation of, the existing psychic structure – a period of disintegration – and finally a secondary integration at a higher level. Dąbrowski feels that no growth takes place without previous disintegration. He regards symptoms of anxiety, psychoneurosis, and even some symptoms of psychosis as the signs of the disintegration stage of this evolution and therefore not always pathological.” (Aronson, 1964, pp. xii-xiv).

⚃ “Crisis refers to the acute disturbance that may occur in an individual as a result of an emotional hazard. During a crisis the individual shows increased tension, unpleasant affect, and disorganized behavior. His attempts at solution may end in his returning to his former psychic equilibrium or may advance him to a healthier integration. However, if the problem has been beyond his capacity to handle, he will show nonadaptive solutions and will have restored equilibrium at a lower level of integration. Lindemann emphasizes the importance of significant persons in the individual’s life during the time of a crisis. Even minor influences of a significant person at this time may determine the outcome of the crisis in one direction or another. In the course of life, all people have experienced many such crises, the outcome of which has determined their personality, their creativity, and their mental health.

What Lindemann describes as “crisis” (increased tension, unpleasant affect, and disorganized behavior) is termed “symptoms of disintegration” by Dąbrowski, who feels that, although this process may have either a positive or a negative result, in the vast majority of cases the outcome is positive. Dąbrowski sees a negative outcome only when the environmental situation is very unfavorable or when there is a severe physiological process present” (Aronson, 1964, pp. xx-xxi).

⚃ “The effect of disintegration on the structure of the personality is influenced by such factors as heredity, social environment, and the stresses of life. … Disintegration may be classified as unilevel, multilevel, or pathological; and it may be described as partial or global, permanent or temporary, and positive or negative” (Dąbrowski, 1964, p. 6).

⚃ “The symptoms of anxiety, nervousness, and psychoneurosis, as well as many cases of psychosis, are often an expression of the developmental continuity. They are processes of positive disintegration and creative nonadaptation” (Dąbrowski, 1964, p. 13).

⚃ “During periods of developmental crisis (such as the age of opposition and especially puberty) there are many more symptoms of disintegration than at other times of life. These are also the occasions of greatest growth and development. The close correlation between personality development and the process of positive disintegration is clear.

Symptoms of positive disintegration are also found in people undergoing severe external stress. They may show signs of disquietude, increased reflection and meditation, self-discontentment, anxiety, and sometimes a weakening of the instinct of self-preservation. These are indications both of distress and of growth. Crises are periods of increased insight into oneself, creativity, and personality development” (Dąbrowski, 1964, p. 18).

⚃ “How can positive disintegration be differentiated from negative disintegration? The prevalence of symptoms of multilevel disintegration over unilevel ones indicates that the disintegration is positive. The presence of consciousness, self-consciousness, and self-control also reveals that the disintegration process is positive. The predominance of the global forms, the seizing of the whole individuality through the disintegration process, over the narrow, partial disintegration would prove, with other features, its positiveness. Other elements of positive disintegration are the plasticity of the capacity for mental transformation, the presence of creative tendencies, and the absence or weakness of automatic and stereotyped elements” (Dąbrowski, 1964, p. 19).

⚃ Dąbrowski believed that normal development is limited by the influence of socialization.

≻ He did not feel that inculcation and socialization represented authentic development and he suggested that the early psychological concepts and structures built upon socialization had to be broken apart and dis-integrated in order to allow the individual to create their own unique personality.

⚃ Dąbrowski observed that a few people in the population, probably about 5%, have difficulty controlling their impulses and instincts and conforming to socialization.

≻ These individuals display overt antisocial behavior.

⚃ The average person, probably about 60% of the population, becomes socialized and adopts the prevailing mores, roles and expectations of the given culture.

≻ Contrary to conventional wisdom in psychology and psychiatry, Dąbrowski did not feel that adjustment to one’s culture was a positive feature.

≻ Dąbrowski went as far as to say such adjustment represented the opposite of mental health.

≻ Likely influenced by philosophy (Plato and Nietzsche) Dąbrowski took the position that authentic development had to reflect a very conscious and volitional examination of one’s essential character and the construction of a unique hierarchy of values reflecting one’s unique character and personality.

⚃ This approach challenges the traditional view of symptoms as negative aspects that must be treated through palliation or resolution.

≻ Instead, Dąbrowski said that psychological symptoms, represented by psychoneuroses, were not only positive, but necessary for advanced personality development.

⚃ “In general, disintegration refers to involution, psychopathology, and retrogression to a lower level of psychic functioning. Integration is the opposite: evolution, psychic health, and adequate adaptation, both within the self and to the environment. Dąbrowski postulates a developmental instinct: that is, a tendency of man to evolve from lower to higher levels of personality” (Dąbrowski, 1964, p. xiv).

⚃ “Disintegration of the primitive structures destroys the psychic unity of the individual. As he loses the cohesion which is necessary for feeling a sense of meaning and purpose in life, he is motivated to develop himself. The developmental instinct, then, following disintegration of the existing structure of personality, contributes to reconstruction at a higher level” (Dąbrowski, 1964, p. 3).

⚃ “The term disintegration is used to refer to a broad range of processes, from emotional disharmony to the complete fragmentation of the personality structure, all of which are usually regarded as negative” (Dąbrowski, 1964, p. 5).

⚃ “Disintegration is the basis for developmental thrusts upward, the creation of new evolutionary dynamics, and the movement of the personality to a higher level, all of which are manifestations of secondary integration” (Dąbrowski, 1964, p. 6).

⚃ Classification of disintegration. “Disintegration may be classified as unilevel, multilevel, or pathological; and it may be described as partial or global, permanent or temporary, and positive or negative” (Dąbrowski, 1964, p. 6).

⚃ “Unilevel disintegration occurs during developmental crises such as puberty or menopause, in periods of difficulty in handling some stressful external event, or under psychological and psychopathological conditions such as nervousness and psychoneurosis. Unilevel disintegration consists of processes on a single structural and emotional level; there is a prevalence of automatic dynamisms with only slight self-consciousness and self-control” (Dąbrowski, 1964, p. 6).

⚄ Prolongation of unilevel disintegration often leads to reintegration on a lower level, to suicidal tendencies, or to psychosis. Unilevel disintegration is often an initial, feebly differentiated borderline state of multilevel disintegration” (Dąbrowski, 1964, p. 7).

⚃ “In multilevel disintegration there is a complication of the unilevel process by the involvement of additional hierarchical levels. There is loosening and fragmentation of the internal environment, as in unilevel disintegration, but here it occurs at both higher and lower strata. These levels are in conflict with one another; their valence is determined by the disposing and directing center, which moves the individual in the direction of his personality ideal. The actions of multilevel disintegration are largely conscious, independent, and influential in determining personality structure” (Dąbrowski, 1964, p. 8).

⚃ Partial disintegration involves only one aspect of the psychic structure, that is, a narrow part of the personality. Global disintegration occurs in major life experiences which are shocking; it disturbs the entire psychic structure of an individual and changes the personality. Permanent disintegration is found in severe, chronic diseases, somatic as well as psychic, and in major physical disabilities such as deafness and paraplegia, whereas temporary disintegration occurs in passing periods of mental and somatic disequilibrium. Disintegration is described as positive when it enriches life, enlarges the horizon, and brings forth creativity; it is negative when it either has no developmental effects or causes involution” (Dąbrowski, 1964, p. 8).

⚃ “The prevalence of symptoms of multilevel disintegration over unilevel ones indicates that the disintegration is positive. The presence of consciousness, self-consciousness, and self-control also reveals that the disintegration process is positive. The predominance of the global forms, the seizing of the whole individuality through the disintegration process, over the narrow, partial disintegration would prove, with other features, its positiveness. Other elements of positive disintegration are the plasticity of the capacity for mental transformation, the presence of creative tendencies, and the absence or weakness of automatic and stereotyped elements” (Dąbrowski, 1964, p. 19).

⚃ “Partial secondary integrations occur throughout life as the result of positive resolutions of minor conflicts” (Dąbrowski, 1964, p. 20).

⚃ “As secondary integration increases, internal psychic tension decreases, as does movement upward or downward of the disposing and directing center, with the conservation, nevertheless, of ability to react flexibly to danger. The disintegration process, as it takes place positively, transforms itself into an ordered sequence accompanied by an increasing degree of consciousness” (Dąbrowski, 1964, p. 21).

⚃ “Crises are periods of increased insight into oneself, creativity, and personality development” (Dąbrowski, 1964, p. 18).

⚃ “In the normal subject [normal intelligence] disintegration occurs chiefly through the dynamism of the instinct of self-improvement, but in the genius it takes place through the instinct of creativity” (Dąbrowski, 1964, p. 22).

⚃ [The sequence of transformations] “occur only if the developmental forces are sufficiently strong and not impeded by unfavorable external circumstances. This is, however, rarely the case. The number of people who complete the full course of development and attain the level of secondary integration is limited. A vast majority of people either do not break down their primitive integration at all, or after a relatively short period of disintegration, usually experienced at the time of adolescence and early youth, end in a reintegration at the former level or in partial integration of some of the functions at slightly higher levels, without a transformation of the whole mental structure” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 4).

⚃ “The term positive disintegration will be applied in general to the process of transition from lower to higher, broader and richer levels of mental functions. This transition requires a restructuring of mental functions” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 18).

⚃ “Experiences of shock, stress and trauma, may accelerate development in individuals with innate potential for positive development” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 20).

⚃ “In the process of multidimensional disintegration, the individual goes beyond his biopsychological developmental cycle, his animalistic nature, his biological determination and slowly achieves psychological and moral self-determination. The human individual, under these conditions ceases to direct himself exclusively by his innate dynamisms and by environmental influences, but develops autonomous dynamisms such as “subject-object” in oneself, the third factor, or personality ideal” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 60).

⚃ “We are human inasmuch as we experience disharmony and dissatisfaction, inherent in the process of disintegration” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 122).

⚃ “Positive or developmental disintegration effects a weakening and dissolution of lower level structures and functions, gradual generation and growth of higher levels of mental functions and culminates in personality integration” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 165).

⚃ “In the course of evolution from higher animals to man, and from the normal man to the universally and highly developed man, we observe processes of disintegration of lower functions and an integration of higher functions” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 62).

⚃ “The developmental process in which occur ‘collisions’ with the environment and with oneself begins as a consequence of the interplay of three factors: developmental potential, … an influence of the social milieu, and autonomous (self-determining) factors” Dąbrowski (1972, p 77).

⚃ “One also has to keep in mind that a developmental solution to a crisis means not a reintegration but an integration at a higher level of functioning” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 245).

⚃ “Inner conflicts often lead to emotional, philosophical and existential crises” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 196).

⚃ “There are four stages of positive disintegration forming an invariant sequence: (1) unilevel disintegration, (2) spontaneous multilevel disintegration, (3) organized multilevel disintegration, (4) transition to secondary integration.” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 301).

⚃ “The chances of developmental crises and their positive or negative outcomes depend on the character of the developmental potential, on the character of social influence, and on the activity (if present) of the third factor” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 245).

⚃ “Every authentic creative process consists of ‘loosening’, ‘splitting’ or ‘smashing’ the former reality. Every mental conflict is associated with disruption and pain; every step forward in the direction of authentic existence is combined with shocks, sorrows, suffering and distress” (Dąbrowski, 1973, p. 14).

⚂ 3.4.3 Psychoneuroses is not an illness / Neurosis:

⚃ Dąbrowski differentiated neuroses from psychoneuroses.

≻ Neuroses are disorders characterized by physiological and psychosomatic processes and, as such, they represent primary or lower level disorders.

≻ Psychoneuroses reflect a different, higher type of experience.

≻ Psychoneuroses were defined as not only necessary for growth but as a type of growth.

≻ Symptoms of psychoneuroses were seen as signs of potential for advanced, and possibly accelerated, development.

≻ Psychoneuroses play a critical role in creating the dis-ease – the internal motivation, and the internal conflicts necessary to trigger self-examination and to stimulate the process of development.

⚃ “[psychoneuroses] show symptoms of disharmony and conflicts within the inner psychic milieu and with the external environment. The source of disharmony and conflicts is a favorable hereditary endowment and the ability to accelerate development through positive disintegration towards personality, i.e. towards a cohesive structure of functions at secondary integration. This conception of psychoneuroses does not consider them pathological, but rather as positive forces in mental development” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 176).

⚃ “The psychoneurotic problem is one of the lack of adjustment manifesting protest against actual reality, and the need for adjustment to hierarchy of higher values: to adjust to that which “ought to be” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 3).

⚃ “Psychoneurotics, rather than being treated as ill, should be considered as individuals most prone to a positive and even accelerated psychic development” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 4).

⚃ Psychoneurosis “represents a ‘hierarchy of higher functions,’ which means a hierarchy in which mental dynamisms predominate over nervous reactions. Psychoneurosis is a more psychical or more mental form of functional disorder, while neurosis is a more nervous or somatopsychic form” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 41).

⚃ “Nervousness, neuroses, and especially psychoneuroses, bring the nervous system to a state of greater sensitivity. They make a person more susceptible to positive change. The higher psychic structures gradually gain control over the lower ones. The lower psychic structures undergo a refinement in this process of inner psychic transformation. This transformation is the fruition of the developmental potential which makes these states possible and makes possible further development” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 41).

⚃ Neurosis: “Psychophysiological or psychosomatic disorders characterized by a dominance of somatic processes. There are no detectable organic defects, although the functions may be severely affected” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 299).

⚃ Psychoneurosis: “A more or less organized form of growth through positive disintegration. Lower psychoneuroses are predominantly psychosomatic in nature, higher psychoneuroses are highly conscious internal struggles whose tensions and frustrations are not anymore translated into somatic disorders” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 303).

⚃ “'Psychoneurotic experiences’ by disturbing the lower levels of values help gradually to enter higher levels of values, i.e. the level of higher emotions. These emotions becoming conscious and ever more strongly experienced begin to direct our behaviour and bring it to a higher level” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 3).

⚃ “In psychoneuroses the highest neuropsychic centres are active and provide a decisive source of psychotherapeutic and developmental energies” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 160).

⚃ “Nervousness and psychoneuroses are structural conditions of sensitivity within and towards one’s own inner psychic milieu wherein positive development through unilevel and multilevel disintegration finds especially favourable ground” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 159).

⚃ “The presence of neurotic or psychoneurotic positive developmental potential guarantees creative development through higher forms of psychoneurotic processes such as internal conflicts, hierarchization, development of autonomous and authentic dynamisms, towards a high level of personality and secondary integration” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 12).

⚃ “The higher the functions in psychoneurosis, the more one uncovers elements of personality development in the subject” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 197).

⚃ “Psychoneuroses especially those of a higher level – provide an opportunity to ‘take one’s life into one’s own hands.’ They are expressive of a drive for psychic autonomy, especially moral autonomy, through transformation of a more or less primitively integrated structure” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 4).

⚃ “Psychoneuroses are observed in people possessing special talents, sensitivity, and creative capacities; they are common among outstanding people” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 2).

⚃ “'Psychoneurotic experiences’ by disturbing the lower levels of values help gradually to enter higher levels of values, i.e. the level of higher emotions” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 3).

⚃ “In the higher psychoneuroses we have ‘seeing’ of new things, answers to the meaning of life, a search for the ‘new and other,’ separation into levels …” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 199).

⚃ “The general basic condition for the genesis and development of neuroses and psychoneuroses is – in our opinion – an increased psychic excitability [overexcitability]” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 46).

⚃ “Generally speaking psychoneuroses should be considered a basic constituent of the process of positive disintegration and a developmentally positive group of dynamisms and syndromes, connected with the tension arising from strong developmental conflicts” (Dąbrowski, 1973, p. 149).

⚃ Psychoneuroses: “those processes, syndromes and functions which express inner and external conflicts, and positive maladjustment of an individual in the process of accelerated development” (Dąbrowski, 1973, p. 151).

⚃ Psychoneuroses are “connected with the tension arising from strong developmental conflicts” (Dąbrowski, 1973, p. 149) and “contain elements of man’s authentic humanization” (Dąbrowski, 1973, p. 152).

⚃ “psychoneuroses are the protection against serious mental disorders – against psychoses” (Dąbrowski, 1973, p. 162).

⚂ 3.4.4 Multilevelness (Unilevelness, Levels of functions):

⚃ In describing the average development and behavior of individuals, Dąbrowski observed that most psychological reactions tend to be rote, reflexive and lacking any deep sense of consciousness or awareness. This lack of consciousness often leads to a robotic character in an individual’s responses. Dąbrowski called this unilevelness.

⚃ A qualitatively different and radical shift in perception marks advanced development. This shift, referred to by Dąbrowski as multilevelness, is characterized by a conscious comparison of, and evaluation of, what is lower versus what is higher. Eventually, this vertical analysis comes to influence one’s reactions and behavior. Dąbrowski believed that if an authentic individual is able to see the higher alternative in comparison to the lower, he or she would choose the higher.

⚃ Reality and our perception of reality can be differentiated into a hierarchy of levels.

⚃ The reality that each person perceives reflects their given level of development.

⚃ Psychological functions go through both quantitative and qualitative changes in the course of development.

⚃ These changes allow people to differentiate higher, more developed levels from lower, earlier, less developed levels.

⚃ The shift from unilevelness to multilevelness represents a fundamental qualitative change in the perception of reality of an individual.

⚃ Differentiation of these lower and higher levels constitutes a multilevel view – this is fundamental to Dąbrowski’s conception of mental health and of development.

⚃ “Lower levels of functions are characterized by automatism, impulsiveness, stereotypy, egocentrism, lack or low degree of consciousness. …

≻ Higher levels of functions show distinct consciousness, inner psychic transformation, autonomousness, creativity” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 297).

⚃ “By higher level of psychic development we mean a behavior which is more complex, more conscious and having greater freedom of choice, hence greater opportunity for self-determination” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 70).

⚃ Multilevelness: “Division of functions into different levels, for instance, the spinal, subcortical, and cortical levels in the nervous system. Individual perception of many levels of external and internal reality appears at a certain stage of development, here called multilevel disintegration” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 298).

⚃ “It appears obvious that the ability to understand and to successfully apply the concept of multilevelness depends upon the development of personality of the individual” (Dąbrowski, 1973, p. x).

⚃ Unilevelness: “unilevelness;” that is to say, the absence of the dynamisms of hierarchization of oneself into “lower” and “higher,” more and less developed elements which are closer to or distant from one’s personality (Dąbrowski, 1973, p. 43).

⚃ “In the theory of positive disintegration we distinguish various levels of development of emotional and instinctive functions. The level of these functions determines the level of values. The concept of hierarchy of values is based on the distinction of levels of emotional and instinctive development of individuals as well as social groups. We hold the opinion that it is possible to obtain in valuation a degree of objectivity comparable to that of scientific theories. It is characteristic that, for instance, moral judgments made by individuals representing a very high level of universal mental development display a very high degree of agreement” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 92).

⚃ “The qualitative and quantitative differences which appear in mental functions as a result of developmental changes. Lower levels of functions are characterized by automatism, impulsiveness, stereotypy, egocentrism, lack or low degree of consciousness” (Dąbrowski, 1972, pp. 297-298).

⚃ “The developmental sequences of positive disintegration are non-ontogenetic. They are measured in terms of levels attained in the course of development which has no distinct time schedule … The levels of development are, therefore, a non-ontogenetic evolutionary scale” (Dąbrowski, 1996, p. 23).

⚃ “The developmental transformations are characterized by a transition from unilevelness to multilevelness, from ahierarchic to hierarchic structures, from a narrow to a broad understanding of reality, entailing the capacity for reflecting on one’s past history (retrospection) and for envisaging future conflicts with one-self and tasks of one’s personal growth (prospection)” (Dąbrowski, 1996, p. 26).

⚃ Primary Integration

⚄ Primary Integration (Primitive integration, Level I):

⚄ Definition: “An integration of all mental functions into a cohesive structure controlled by primitive drives” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 302).

⚄ “Individuals with some degree of primitive integration comprise the majority of society” (Dąbrowski, 1964,p. 4).

⚄ “Among normal primitively integrated people, different degrees of cohesion of psychic structure can be distinguished” (Dąbrowski, 1964, p. 66).

⚄ “Psychopathy represents a primitive structure of impulses, integrated at a low level” (Dąbrowski, 1964, p. 73).

⚄ “The first stage, called primitive or primary integration, is characterized by mental structures and functions of a low level; they are automatic and impulsive, determined by primitive, innate drives. At this stage, intelligence neither controls nor transforms basic drives. It is used in a purely, instrumental way, so as to supply the means towards the ends determined by primitive drives” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 21).

⚄ “PRIMITIVE INTEGRATION, or primary integration, an integration of mental functions, subordinated to primitive drives (cf.). There is no hierarchy of instincts; their prevalence depends entirely on their momentary greater intensity. Intelligence is used only as a tool, completely subservient to primitive urges, without any transformative role. Interest and adaptation are limited to the satisfaction of primitive desires. There is no inner psychic milieu, no mental transformation of stimuli, no inner conflicts” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 176).

⚄ [Comment: In primary integration reactions are based primarily on stimuli and there is little psychological intervention between the stimulus and the response.

≻ Responses are based primarily upon instinctual factors and socially ingrained responses.

≻ People learn socially appropriate behavior, for example, one learns that when sitting listening to a funeral eulogy, one does not laugh.

≻ Let me provide an illustration from a hypothetical movie. I'm sitting in an aisle seat when beside me, in the dark, an older woman stumbles and spills her popcorn. At first several people laugh and, for an instant, I catch myself laughing along. However, I quickly see the situation and inhibit my laughter and get up to help the lady who has fallen. The man in front of me continues to laugh and turns to his partner and says, look at that clumsy fool.”

≻ In primary integration there is no inner psychic milieu to process the stimulus in order to arrive at an appropriate behavioral response.

≻ There is no internal mechanism to inhibit lower responses or to replace lower responses with higher ones.

≻ By nature, lower responses tend to be instinctual, automatic, socially based and immediate.

≻ Higher responses need the intervention of an internal thought process.

≻ The stimulus literally must be filtered through one’s personality and in this way, the behavioral response will reflect the individual’s unique personality ideal.]

⚄ “A primitively integrated individual spends his life in the pursuit of satisfying his basic needs. He is controlled by the integrated structure of his instincts, and his intelligence is in their service. He responds to social influence only as a measure of self-preservation. There are no internal conflicts. Mental disorders are characterized by lack of response to social influence, i.e. other individuals are perceived and used as objects” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 111).

⚃ Unilevel disintegration

⚄ “Among the first symptoms of disintegration are increased sensitivity to internal stimuli, vague feelings of disquietude, ambivalences and ambitendencies, various forms of disharmony and, gradually, the appearance of nuclei of hierarchization. This process of hierarchic differentiation applies to both the external stimuli and to one’s own mental structure. At the beginning this hierarchization is very weak. There is a continuous vacillation of ‘pros’ and ‘cons,’ no clear direction ‘up’ or ‘down.’” (Dąbrowski, 1970, pp. 21-22).

⚄ “Prolonged states of unilevel disintegration (level II) end either in a reintegration at the former primitive level or in suicidal tendencies, or in a psychosis” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 135).

⚄ “protracted and recurrent conflicts between drives and emotional states of a similar developmental level and of the same intensity, e.g. states of ambivalence and ambitendency, propulsion toward and repulsion from the same object, rapidly changing states of joy and sadness, excitement and depression without the tendency towards stabilization within a hierarchy” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 165).

⚄ “It [unilevel disintegration] consists of disintegrative processes occurring as if on a single structural level. There is disintegration but no differentiation of levels of emotional or intellectual control. Unilevel disintegration begins with the loosening of the cohesive and rigid structure of primary integration. There is hesitation, doubt, ambivalence, increased sensitivity to internal stimuli, fluctuations of mood, excitations and depressions, vague feelings of disquietude, various forms of mental and psychosomatic disharmony. There is ambitendency of action, either changing from one direction to another, or being unable to decide which course to take and letting the decision fall to chance, or a whim of like or dislike. Thinking has a circular character of argument for argument’s sake. Externality is still quite strong. Nuclei of hierarchization may gradually appear weakly differentiating events in the external milieu and in the internal milieu [inner psychic milieu] but still there is continual vacillation between “pros” and “cons” with no clear direction out of the vicious circle. Internal conflicts are unilevel and often superficial. When they are severe and engage deeper emotional structures the individual often sees himself caught in a “no exit” situation. Severe mental disorders are associated with unilevel developmental structure” (Dąbrowski, 1996, p. 18).

⚃ Spontaneous multilevel disintegration

⚄ “the time of the appearance of such developmental dynamisms as astonishment with oneself, disquietude with oneself, dissatisfaction with oneself, feelings of shame and guilt, feeling of inferiority toward oneself. The individual searches not only for novelty, but for something higher; he searches for examples and models in his external environment and in himself. He starts to feel the difference between a higher and a lower level. We can notice the formation of the critical awareness of oneself and other people, awareness of one’s ‘essence’ as it arises from one’s existence. Spontaneous multilevel disintegration is the crucial period of positive, developmental transformations” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 22).

⚄ “characterized by a relative predominance of spontaneous developmental forces” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 165).

⚄ “Internal experiential factors begin to control behavior more and more, wavering is replaced by a growing sense of ‘what ought to be” as opposed to ‘what is’ in one’s personality structure. Internal conflicts are numerous and reflect a hierarchical organization of cognitive and emotional life: ‘what is’ against ‘what ought to be’ (Dąbrowski, 1996, p. 19).

⚄ “Spontaneous multilevel disintegration is a crucial period for positive, i.e. developmental transformations. The loosening and disintegration of the inner psychic milieu occurs at higher and lower strata at the same time. This means that the whole personality structure is affected by this process” (Dąbrowski, 1996, p. 19).

⚃ Organized multilevel disintegration

⚄ “exhibits more tranquility, systematization and conscious transformation of oneself. The developmental dynamisms which distinctly appear at this stage are: “subject-object” in oneself; the third factor, self-awareness and self-control, identification and empathy, education of oneself and autopsychotherapy. The ideal of personality takes more distinct contours and becomes closer to the individuals. There is a pronounced growth of empathy” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 22).

⚄ “organized (self-directed), as it is in the period of conscious organization and direction of the processes of disintegration towards secondary integration and personality” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 165).

⚄ “While tensions and conflicts are not as strong as at the previous level, autonomy and internal hierarchy of values and aims are much stronger and much more clearly developed. The ideal of personality becomes more distinct and closer. There is a pronounced growth of empathy as one of the dominants of behavior and development” (Dąbrowski, 1996, p. 19).

⚃ Secondary Integration

⚄ “consists in a new organization and harmonization of personality. The main dynamism active at this stage are: autonomy and authentism, disposing and directing center on a high level, a subtle highly refined empathy, activation of the personality ideal. The relationship of ‘I’ and ‘Thou’ takes on a new dimension. There appears a growing need to transcend the sensory, ‘verifiable’ reality toward the empirical reality which can be attained through intuition, contemplation, and ecstasy rather than through the senses” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 22).

⚄ Definition: “the integration of all mental functions into a harmonious structure controlled by higher emotions such as the dynamism of personality ideal, autonomy and authenticity” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 304).

⚄ “marks a new organization and harmonization of personality. Disintegrative activities arise only in retrospection. Personality ideal is the dominant dynamism in close union with empathy, and the activation of the ideal. The relationship of “I” and “Thou” takes on the dimension of an absolute relationship on the level of transcendental empiricism” (Dąbrowski, 1996, p. 19).

⚂ 3.4.5 Developmental potential:

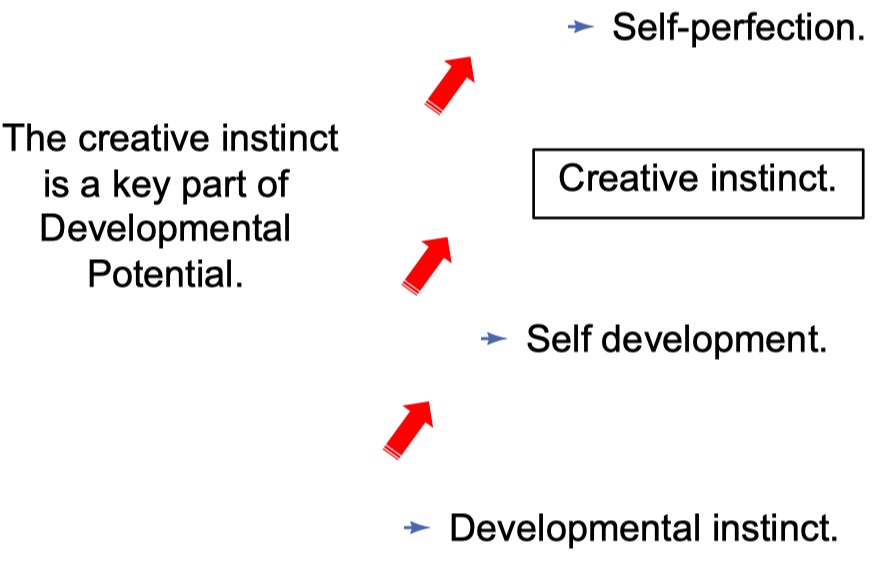

⚃ Dąbrowski described a complex, genetically based constellation of “original endowment,” which includes instincts (the developmental instinct, creative instinct, and instinct for self-perfection, etc.), various dynamisms, nervousness (also known as overexcitability), autonomous forces (the third factor), and other characteristics that he referred to as developmental potential.

≻ He believed that strong positive developmental potential could overcome lower (animal) instinctual influences and socialization to lead to advanced development.

≻ “Psychic overexcitability is one of the recognizable components of the developmental potential” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 65).

⚃ Dąbrowski also linked several other components with developmental potential, including the three factors of development, psychoneuroses, positive disintegration, and emergent internal features of self (such as the hierarchy of values, the inner psychic milieu, personality ideal, and the disposing and directing center).

⚃ Although Dąbrowski identified the third factor as one method to assess developmental potential, no test or measure of this factor has yet been developed and none of the subsequent literature on overexcitability has included the third factor as a component.

⚃ Dąbrowski also linked developmental potential with the presence of psychoneuroses, an early and necessary early step in development.

⚃ The sequence of transformations “occur only if the developmental forces are sufficiently strong and not impeded by unfavorable external circumstances. This is, however, rarely the case. The number of people who complete the full course of development and attain the level of secondary integration is limited. A vast majority of people either do not break down their primitive integration at all, or after a relatively short period of disintegration, usually experienced at the time of adolescence and early youth, end in a reintegration at the former level or in partial integration of some of the functions at slightly higher levels, without a transformation of the whole mental structure” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 4).

⚃ “The developmental instinct acts against the automatic, limited, and primitive functional patterns of the biological cycle of life” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 28).

⚃ Strong developmental potential causes an individual to rebel “against the common determining factors in his external environment” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 32).

⚃ “The individual with a rich developmental potential rebels against the common determining factors in his external environment” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 32).

⚃ “If the developmental potential is distinctly positive or negative, the influence of the environment is less important. If the developmental potential does not exhibit any distinct quality, the influence of the environment is important and it may go in either direction. If the developmental potential is weak or difficult to specify, the influence of the environment may prove decisive, positively or negatively” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 34).

⚃ “Innate developmental potentials may be more general or more specific, more positive or more negative” and may be strong, equivocal or weak (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 33).

⚃ “It is the task of therapy to convince the patient of the developmental potential that is contained in his psychoneurotic processes. Obviously, to achieve that one has to show him this clearly and precisely on the concrete creative and ‘pathological’ dynamisms that are active in his case” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. viii). Thus, the presence of psychoneurotic dynamisms can be taken as another measurable sign of developmental potential.

⚃ Strong developmental potential (either positive or negative) is expressed regardless of the environment. Mild developmental potential may not be expressed unless the environment is optimal, if the potential is “not universal and of weak tension,” the “environmental influence is to a very great degree responsible for the path which will be taken” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 12).

⚃ “The developmental process in which occur ‘collisions’ with the environment and with oneself begins as a consequence of the interplay of three factors: developmental potential, … an influence of the social milieu, and autonomous (self-determining) factors” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 77).

⚃ “The relations and interactions between the different components of the developmental potential give shape to individual development and control the appearance of psychoneuroses on different levels of development” Dąbrowski (1972, p. 78).

⚃ People with strong developmental potential “must have much more time for a deep, creative development and that is why [you] will be growing for a long time. This is a very common phenomenon among creative people. Simply, they have such a great developmental potential, ‘they have the stuff to develop’ and that is why it takes them longer to give it full expression” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 272).

⚃ Definition: “The constitutional endowment which determines the character and the extent of mental growth possible for a given individual” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 293).

⚃ Dąbrowski selected three aspects he felt could be used to assess developmental potential. “Developmental potential can be assessed on the basis of the following components: psychic overexcitability, special abilities and talents, and autonomous factors (notably the third factor)” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 293).

⚃ “No experiences, no shocks, no breakdowns will trigger growth if the embryo of what is to develop is not there” (Cienin [Dąbrowski], 1972a, p. 38).

⚃ “The whole process of transformation of primitive drives and impulsive functions into more reflective and refined functions occurs under the influence of evolutionary dynamisms which we call the developmental instinct” (Dąbrowski, 1973, p. 22).

⚃ “The developmental potential can be limited to the first and the second factors only. In that case we are dealing with individuals who throughout their life remain in the grip of social opinion and their own psychological typology (e.g. social climbers, fame seekers, those who say ‘I was born that way’ or ‘I am the product of my past’ and do not conceive of changing)” (Dąbrowski, 1996, pp. 14-15).

⚂ 3.4.6 The three factors of development:

⚃ Dąbrowski described three factors influencing behavior and development.