⚁ 1.1 Overview.

⚂ 1.1.1 Kazimierz Dąbrowski was a Polish psychiatrist and psychologist known for his theory of positive disintegration.

≻ Although not widely recognized, his approach represents a precursor to contemporary studies of posttraumatic growth.

≻ Dąbrowski’s theory suggests that personal growth and development often involve a process of disintegrating existing psychological structures primarily based on socialization.

≻ This disintegrative/growth process is driven by developmental potential, a constellation of traits possessed by a minority of individuals.

≻ Thus, in this theory, growth is not universal – maximum development is uncommon.

≻ In ideal development, disintegration is followed by the reorganization of the self.

≻ One takes an active role in the formulation of a self-constructed personality based on an internal locus of control.

≻ This “new” self is shaped by a unique hierarchy of values, aims, and goals that best reflect the individual’s true nature – the fundamental character traits that express their deep essence.

≻ In Dąbrowski’s formulation, these developmental exemplars represent what it means to be an authentic human being.

⚁ 1.2 The origins of the theory.

≻ Dąbrowski’s life intersected with two world wars, leading him to witness the lowest forms of depravity and behavior imaginable. In these grim moments, he also encountered profound self-sacrifice and genuine human authenticity.

≻ He said he could not find a psychological theory that included both extremes and reconciles how these two extremes can both be components of human behaviour. What drives a person to behave like a monster? How does an average person rise to become a hero? How can we comprehend the average person’s vulnerability to sacrificing their autonomy and blindly, without reflection, fall under the spell of a monstrous dictator? Or, more subtly, robotically follow the dictates of society? How can people cultivate autonomy and develop a truly unique personality? How can people work towards an ideal, both for themselves and for their society?

≻ Based on his life observations, Dąbrowski developed his theory to address these questions.

⚁ 1.3 Brief overview of the theory.

⚂ 1.3.1 Dabrowski believed that socialization curtails individual growth.

≻ Emphasizing a positive definition of mental health, Dąbrowski said mental health involves more than merely adopting and adapting to societal norms or expectations.

≻ Instead, mental health emphasizes self-transformation in creating and pursuing higher ideals that shape a unique, authentic, and autonomous personality.

≻ Disintegrating the initial socialized psychological structures is necessary to create opportunities for the individual to take growth into their own hands.

≻ Lower structures are replaced by integrations into new, higher structures.

≻ Higher structures are consciously chosen to reflect the values and essence of the individual.

≻ At the highest level, a self chosen and self created unique and autonomous personality comes to guide behaviour.

≻ Disintegration requires a constellation of factors Dąbrowski called developmental potential.

⚂ These ideas are captured in the following quotation by Aldous Huxley:

“We see, then, that modern technology has led to the concentration of economic and political power and to the development of a society controlled (ruthlessly in the totalitarian states, politely and inconspicuously in the democracies) by Big Business and Big Government. But societies are composed of individuals and are good only insofar as they help individuals to realize their potentialities and to lead a happy and creative life. How have individuals been affected by the technological advances of recent years? Here is the answer to this question given by a philosopher-psychiatrist, Dr. Erich Fromm:

‘Our contemporary Western society, in spite of its material, intellectual and political progress, is increasingly less conducive to mental health, and tends to undermine the inner security, happiness, reason and the capacity for love in the individual; it tends to turn him into an automaton who pays for his human failure with increasing mental sickness, and with despair hidden under a frantic drive for work and so-called pleasure.’

Our ‘increasing mental sickness’ may find expression in neurotic symptoms. These symptoms are conspicuous and extremely distressing. But ‘let us beware,’ says Dr. Fromm, ‘of defining mental hygiene as the prevention of symptoms. Symptoms as such are not our enemy, but our friend; where there are symptoms there is conflict, and conflict always indicates that the forces of life which strive for integration and happiness are still fighting.’ The really hopeless victims of mental illness are to be found among those who appear to be most normal. ‘Many of them are normal because they are so well adjusted to our mode of existence, because their human voice has been silenced so early in their lives, that they do not even struggle or suffer or develop symptoms as the neurotic does.’ They are normal not in what may be called the absolute sense of the word; they are normal only in relation to a profoundly abnormal society. Their perfect adjustment to that abnormal society is a measure of their mental sickness. These millions of abnormally normal people, living without fuss in a society to which, if they were fully human beings, they ought not to be adjusted, still cherish ‘the illusion of individuality,’ but in fact they have been to a great extent deindividualized. Their conformity is developing into something like uniformity. But ‘uniformity and freedom are incompatible. Uniformity and mental health are incompatible too. ... Man is not made to be an automaton, and if he becomes one, the basis for mental health is destroyed.’

In the course of evolution nature has gone to endless trouble to see that every individual is unlike every other individual. We reproduce our kind by bringing the father’s genes into contact with the mother’s. These hereditary factors may be combined in an almost infinite number of ways. Physically and mentally, each one of us is unique. Any culture which, in the interests of efficiency or in the name of some political or religious dogma, seeks to standardize the human individual, commits an outrage against man’s biological nature” (Huxley, 1958, pp. 20-21).

⚂ 1.3.2 Here are several key concepts of the theory:

⚃ Multilevelness and multidimensionality:

≻ Dąbrowski’s approach to analyzing human behaviour emphasized multilevelness – essentially an awareness of and a subsequent comparison of the qualitative differences between the “lower, intermediary, and higher” levels of reality.

≻ Multilevelness reflects an observable hierarchy of mental functions.

≻ This approach leads to a hierarchical description and analysis of psychological structures.

≻ In a general sense, Dąbrowski said unilevel perceptions of reality characterize the lower levels, while multilevel perceptions reflect a deep awareness and breadth of perception.

≻ In a more specific context, unilevel and multilevel are terms used to describe types of internal conflicts.

≻≻ In the basic integration, primary integration, conflicts between the individual and their environment are common however few internal conflicts occur.

≻≻ In unilevel disintegration, conflicts occur on a single plane – between choices that are essentially equivalent.

≻≻ In higher development, multilevel conflicts occur that reflect differences between higher and lower levels.

≻≻ Multilevel – vertical – conflicts challenge the individual – Will you choose the low road or the high road?

≻≻ This choice will be informed by one’s deep essence.

≻≻ Choosing correctly will “Feel right” and affirm the self.

≻≻ Making a choice against one’s essence will result in feelings of guilt and shame.

≻≻ Dąbrowski framed this in terms of making choices that are “less myself” versus “more myself.”

≻ Dąbrowski explained his multilevel analysis is analogous to Plato’s description of the levels of reality.

≻ Multilevel analysis applies to all kinds and types of mental functions and, when combined with a multidimensional approach, creates a powerful descriptive and analytic tool.

⚃ Others have also described these two fundamental aspects:

⚃ Positive disintegration:

≻ In the context of TPD, disintegration refers to the breakdown of the influence and reliance on the second factor: heteronomous development.

≻ This creates the opportunity for the individual to expand the third factor and begin personality shaping in the direction of the personality ideal: this eventually leads to achieving personality – autonomous development.

≻ Disintegration is necessary for multilevel psychological growth.

≻ Disintegration is positive when it ultimately leads to growth.

≻ Disintegration is negative when it leads to:

‘a decrease of consciousness and an increase of destructive processes with a tendency toward involution of the total personality, as in the chronic organic psychoses and the chronic schizophrenic psychoses. The psychic structure gradually fragments, the sphere of consciousness diminishes, and there is a loss of creative capacities” (Dąbrowski, 1964, p. 71).

≻ Disintegration unfolds through psychoneuroses; comprised of strong internal conflicts, crises, and moral dilemmas.

≻ Disintegration involves breaking down “lower” existing psychological structures founded upon external mores, beliefs, and behavioural expectations that become incompatible with higher, self-evaluated, self-defined values, ideals, and potentials.

≻ Role models of exemplary development also point the way.

⚃ Psychoneuroses:

≻ The developing individual begins to recognize that the values they adopted as they were raised no longer feel right – they no longer seem to fit.

≻ These feelings create disharmony and conflicts within one’s inner psychic milieu (one’s internal psychological environment) and with the external environment.

≻ These moral dilemmas and crises are expressed as anxieties and depression – What Dąbrowski called psychoneuroses.

≻ Traditionally, psychology and psychiatry has seen these conditions as abnormalities that need to be ameliorated, usually through medication or counselling.

≻ Based upon his studies of developmental exemplars, Dąbrowski came to see that these anxieties and depressions play a critical role in psychological growth by creating disintegration and allowing the individual to take volitional control over their own development.

≻ Psychoneuroses are the principal vehicle of positive disintegration.

≻ Psychoneuroses in the context of TPD are triggered and driven by strong positive developmental potential.

≻ When occurring with developmental potential, psychoneuroses are a mechanism of growth.

≻ Occurring without developmental potential, psychoneuroses are not generally seen as developmental.

≻ Dąbrowski noted that depression and anxiety act as a precursor to disintegration and are also a byproduct of disintegration.

≻ Psychoneuroses and neuroses reflect and are analyzed based on a hierarchical representation of functions.

≻ Dąbrowski distinguished interneurotic (the hierarchy of different psychoneuroses) and intraneurotic differences (different levels of the same psychoneurosis).

≻ Higher psychoneuroses are more psychic – psychological and mental forms of disorder, in comparison to lower neuroses which are more somatic and nervous in nature.

⚃ Developmental potential:

≻ Dąbrowski identified various “constitutional” (hereditary) factors that determine the character and extent of mental growth possible for a given individual.

≻ ““The developmental potential is the original endowment which determines what level of development a person may reach if the physical and environmental conditions are optimal” (Dąbrowski, 1996, p. 10).

≻ Developmental potential includes instincts, dynamisms, the third factor, overexcitabilities, and special abilities and talents.

≻ Dąbrowski said developmental potential can be

assessed based on overexcitabilities, special abilities and talents, and the third factor.

⚄ Instincts:

≻ Dąbrowski’s approach to instincts is fairly complicated and detailed.

≻ In defining instincts, Dąbrowski called them “a fundamental dynamism” in the lives of animals and men, characterized by great intensity.

≻ Dąbrowski equated the dynamisms with instincts: “The various dynamisms presented here in their structure, action, and transformations we also call instincts. Our reason for including these forces among instincts is that, in our view, they are a common phenomenon at a certain level of man’s development, they are basic derivatives of primitive instinctive dynamism, and their strength often exceeds the strength of the primitive maternal instinct” (Dąbrowski, 1967, p. 54).

≻ In the definition of dynamisms, instincts feature prominently; when combined with emotions, instincts, along with drives and intellectual processes, constitute specific kinds of dynamisms.

≻ Dąbrowski recognized two basic types of instincts: the autonomic (including the self-preservation, possessive, fighting, and other instincts) and the syntonic instincts (“companion-seeking” instinct, sexual drive, maternal or paternal instinct, herd, cognitive, and religious instincts).

≻ Dąbrowski applied a multilevel analysis to instincts, differentiating lower instincts (e.g. self-preservation, aggression [fighting], sexual impulses) versus higher instincts (e.g. partial death instinct, developmental (“the mother”) instinct, creative instinct, transcendental instinct, and the self-perfection instinct). He also described a social instinct characterizing the second factor.

≻ Dąbrowski gave instincts a critical role in development; “A human being at the level of a developing personality controls his instinctive life. This process consists in separating that which, in every instinct or group of instincts, may be considered distinctly human from that which is distinctly animalistic ” (Dąbrowski, 1967, p. 107).

≻ Some instincts are not universal and only occur in people who have obtained a high level of development.

≻ High level instincts become “constitutive elements of personality.”

⚄ Dynamisms:

≻ The theory seeks to understand the forces – the dynamics – that motivate behaviour.

≻ Dąbrowski defined dynamisms as biological or mental forces that control behavior and its development.

≻ Dynamisms are instincts, drives, and intellectual processes combined with

emotions.

≻ Dąbrowski described some 20 dynamisms that influence development and behaviour.

⚄ The Third Factor:

≻ The third factor represents “the totality of all autonomous forces” expressed as a feeling one must discover, evaluate, and develop one’s deep essence or character. This evaluation leads to an image of one’s personality ideal – of one’s ideal self.

≻ The third factor moves the individual towards values and behaviours that reflect how things “ought to be” based on this unique self-evaluation and personality ideal.

≻ The third factor is central; “Along with inborn properties and the influence of environment, it is the ‘third factor’ that determines the direction, degree, and distance of man’s development” (Dąbrowski, 1964, p. 53).

⚄ Overexcitabilities:

≻ Dąbrowski identified five types of overexcitability (psychomotor, sensual, emotional, intellectual, and imaginational) predisposing individuals to experience life more intensely.

≻ Dąbrowski used the terms overexcitability and nervousness synonymously, saying that the term overexcitability denotes a variety of types of nervousness.

≻ Overexcitability is a higher than average responsiveness to stimuli.

≻ Strong overexcitability changes how a person perceives reality, increasing the range and depth of experience.

≻ Overexcitabilities contribute to disintegration by heightening sensitivity and awareness.

≻ “The prefix ‘over’ attached to ‘excitability’ serves to indicate that the reactions of excitation are over and above average in intensity, duration, and frequency” (Dąbrowski, 1996, p. 7).

⚄ Special abilities and talents:

≻ Another component of developmental potential – IQ plus things like musical talent or artistic ability.

⚃ Hierarchization:

≻ Hierarchization is the process of differentiating higher from lower levels in oneself and in the environment.

≻ The comparison between lower and higher helps the individual choose and develop higher levels – this primarily involves emotions and values.

≻ Hierarchization is the beginning of the development of the inner psychic milieu.

⚃ Inner psychic milieu:

≻ The internal mental environment – the totality of mental dynamisms of a low or high degree of consciousness.

≻ In the context of TPD, the inner psychic milieu represents an awareness of one’s internal mental state and processes.

≻ At the level of primary integration, there is no inner psychic milieu.

≻ At the second level, unilevel disintegration, psychological factors begin to play a role, and therefore, an inner psychic milieu appears, however, it remains ahierarchic and undifferentiated.

≻≻ The intrapsychic factors are not transformative, only disintegrative in respect to the cohesive structures of primary integration.

≻ With the appearance of multilevel transformative dynamisms, a hierarchically structured inner psychic milieu is formed.

≻ The development and differentiation of the inner psychic milieu is the distinctive feature of multilevel disintegration and autonomous development.

⚃ The contemporary relevance of the theory.

≻ The conventional goal of psychological therapy is to ameliorate

dis – ease, anxiety, and crisis, restoring stability.

≻ Dąbrowski took a radically different view, emphasizing that periods of disequilibrium, upset, depression, anxiety, and ultimately even chaos and crisis are necessary elements in the process of growth.

≻ For Dąbrowski, positive disintegration does not merely lead to resilience; rather, it creates a higher level of function than before.

≻ The theory predates and reflects the contemporary approach of posttraumatic growth.

⚃ Summary:

≻ The central thesis of the theory is that driven by developmental potential, internal conflicts produce psychoneuroses – strong anxieties and depressions that confront conventional rationales and explanations and force self-examination.

≻ This often leads to loosening unilevel structures, allowing the individual to take development “into their own hands” and begin the developmental process.

≻ Developing a hierarchy of values and personality ideal helps shape the self away from ego and toward a unique and autonomous personality that comes to be expressed in a secondary multilevel integration.

⚁ 1.4 The levels of the theory.

⚂ 1.4.1 In general, Dąbrowski described two fundamentally different perceptions of reality: the unilevel and the multilevel.

≻ Individuals with a unilevel perception of reality will not be aware of the hierarchy of reality.

≻ To advance beyond unilevel experience, one must experience disintegration.

≻ Through the disintegration of unilevel psychological structures, opportunities arise to establish a hierarchical view of life – the foundation of multilevelness.

⚂ Dąbrowski’s theory has five levels: level one represents “An integration of all mental functions into a cohesive structure controlled by primitive drives” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 302).

≻ Level five represents the ultimate level of autonomy and multilevelness – “The integration of all mental functions into a harmonious structure controlled by higher emotions such as the dynamism of personality ideal, autonomy and authenticity” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 304).

≻ Level two signifies unilevel disintegration, while levels three and four indicate multilevel disintegration.

≻ Dąbrowski said the levels are a heuristic device used to describe the corresponding levels observed in human nature.

≻ The heteronomous level – Level I, is determined by biological and social factors (first and second factor).

≻ On the other hand, multilevel life becomes autonomous, characterizing Levels III and above, and reflecting increasing degrees of self-conscious, self-determined, and self-controlled mental development.

≻ Influenced by the third factor as the locus of control shifts from external to internal.

≻ Level II is typically a short transitional phase marked by intense unilevel crises:

≻≻ “Prolongation of unilevel disintegration often leads to reintegration on a lower level, to suicidal tendencies, or to psychosis” (Dąbrowski, 1964b, p. 7).

Also see: link

⚂ 1.4.2 Dr. Mika has suggested that, in today’s era, it would be clearer to describe the levels using the terms “unilevel integration” instead of “primary integration” and “multilevel integration” instead of “secondary integration.”

≻ I fully support this suggestion in future neo-Dąbrowskian works.

⚁ 1.5 Six seminal quotes.

⚂ 1.5.1 “Personality: A self-aware, self-chosen, self-affirmed, and self-determined unity of essential individual psychic qualities. Personality as defined here appears at the level of secondary integration” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 301).

⚂ 1.5.2 “The propensity for changing one’s internal environment and the ability to influence positively the external environment indicate the capacity of the individual to develop. Almost as a rule, these factors are related to increased mental excitability, depressions, dissatisfaction with oneself, feelings of inferiority and guilt, states of anxiety, inhibitions, and ambivalences—all symptoms which the psychiatrist tends to label psychoneurotic. Given a definition of mental health as the development of the personality, we can say that all individuals who present active development in the direction of a higher level of personality (including most psychoneurotic patients) are mentally healthy” (Dąbrowski, 1964, p. 112).

⚂ 1.5.3 “Intense psychoneurotic processes are especially characteristic of accelerated development in its course towards the formation of personality. According to our theory accelerated psychic development is actually impossible without transition through processes of nervousness and psychoneuroses, without external and internal conflicts, without maladjustment to actual conditions in order to achieve adjustment to a higher level of values (to what ‘ought to be’), and without conflicts with lower level realities as a result of spontaneous or deliberate choice to strengthen the bond with reality of higher level” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 220).

⚂ 1.5.4 “Psychoneuroses ‘especially those of a higher level’ provide an opportunity to ‘take one’s life in one’s own hands.’ They are expressive of a drive for psychic autonomy, especially moral autonomy, through transformation of a more or less primitively integrated structure. This is a process in which the individual himself becomes an active agent in his disintegration, and even breakdown. Thus the person finds a ‘cure’ for himself, not in the sense of a rehabilitation but rather in the sense of reaching a higher level than the one at which he was prior to disintegration. This occurs through a process of an education of oneself and of an inner psychic transformation. One of the main mechanisms of this process is a continual sense of looking into oneself as if from outside, followed by a conscious affirmation or negation of conditions and values in both the internal and external environments. Through the constant creation of himself, though the development of the inner psychic milieu and development of discriminating power with respect to both the inner and outer milieus—an individual goes through ever higher levels of ‘neuroses’ and at the same time through ever higher levels of universal development of his personality” (Dąbrowski, 19102, p. 4).

⚂ 1.5.5 “In order to account for differences in the extent of development we introduce the concept of the developmental potential (Dąbrowski, 1970, Piechowski, 1974). The developmental potential is the original endowment which determines what level of development a person may reach if the physical and environmental conditions are optimal” (Dąbrowski, 1996, p. 10).

⚂ 1.5.6 “…in our conception of development the chances of developmental crises and their positive or negative outcomes depend on the character of the developmental potential, on the character of social influence, and on the activity (if present) of the third factor (autonomous dynamisms of self-directed development). One also has to keep in mind that a developmental solution to a crisis means not a reintegration but an integration at a higher level of functioning” (Dąbrowski, 1972, pp. 244-245).

⚁ 1.6 Be Greeted Psychoneurotics.

From the Filmwest movie, Be Greeted Psychoneurotics.

⚂ 1.6.1 “Suffering, aloneness, self-doubt, sadness, inner conflict; these are our feelings that we have not learned to live with, that we have failed to appreciate, that we reject as destructive and completely negative, but in fact they are symptoms of an expanding consciousness.”

≻ “Dr. Kazimierz Dąbrowski has spent 45 years piecing together the complete picture of the growth of the human psyche from primitive integration at birth; the person with potential for development will experience growth as a loosening of the stable psychic structure accompanied by symptoms of psychoneuroses.”

≻ “Reality becomes multileveled, the choices between higher and lower realms of behaviour occupy our thought and mark us as human.”

≻ “Dąbrowski called this process positive disintegration, he declares that psychoneurosis is not an illness and he insists that development does not come through psychotherapy but that psychotherapy is automatic when the person is conscious of his development.”

⚂ 1.6.2 “To Dąbrowski, therapy is autopsychotherapy; it is the self being aware of the self through a long inner investigation; a mapping of the inner environment.

≻ There are no techniques to eliminate symptoms because the symptoms constitute the very psychic richness from which grow an increasing awareness of body, mind, humanity and cosmos. Dąbrowski gives birth to that process if he can.”Without intense and painful introspection and reflection, development is unlikely.

≻ Psychoneurotic symptoms should be embraced and transformed into anxieties about human problems of an ever higher order.

≻ If psychoneuroses continue to be classified as mental illness, then perhaps it is a sickness better than health.”

⚂ 1.6.3 “Without passing through very difficult experiences and even something like psychoneurosis and neurosis we cannot understand human beings and we cannot realize our multidimensional and multilevel development toward higher and higher levels.”

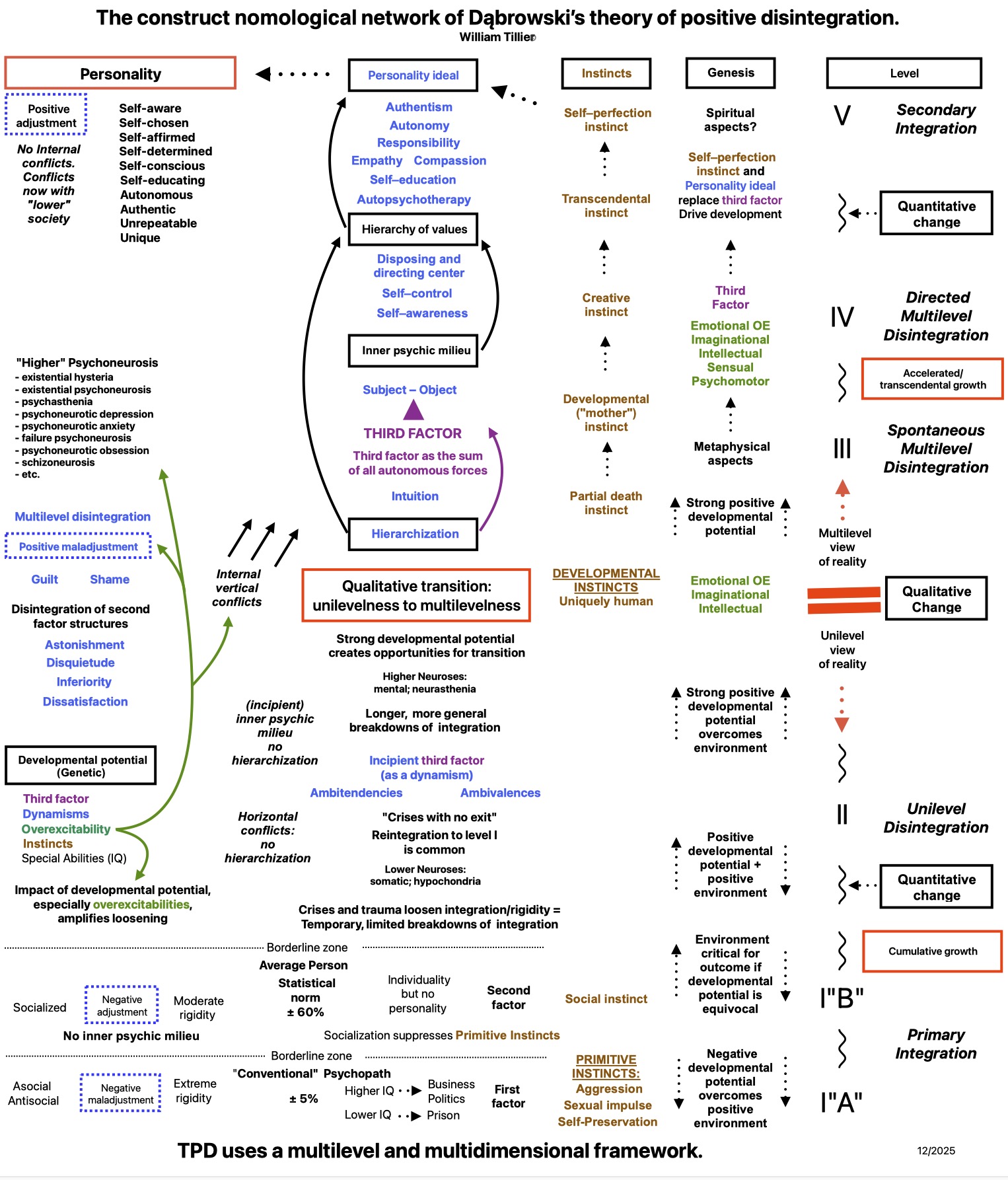

⚁ 1.7 Flow Diagram of TPD.

⚁ 1.8 The construct network of the theory.

⚁ 1.9 Dąbrowski’s work in Canada.

⚂ 1.9.1 Much of the focus of this webpage is on Dąbrowski’s work in Canada.

≻ In 1965, Dąbrowski moved his family to Edmonton and took a visiting professorship at the University of Alberta.

≻ He also held a similar position at Laval University in Québec.

≻ In the years leading up to his death in 1980, he divided his time between Poland and Canada.

≻ Dąbrowski accomplished this work with the help of a number of dedicated people, including Michael Piechowski, Lynn Kealy, Norbert Duda, Marlene Rankel, Dexter Amend, Lorne Yeudall, Francis Lesniak, Leo Mos, Andrzej (Andrew) Kawczak, Tom Nelson, Joseph R. Royce, Peter Jensen, Paul McGaffey, Earle Bain, P. Joshi, J. Sochanska, and P. J. Reese.

≻ From 1976 to 1980, I had the privilege of being a student of Dąbrowski.

≻ He asked me to preserve his theory.

≻ After his passing, I was given the archive of materials he had in Edmonton.

≻ I established this website in 1995.

⚂ 1.9.2 This link provides extensive resources.

⚁ 1.10 Dąbrowski on film. Dąbrowski on film.

![]()