Print or print to save as PDF.

⚃ 9.4.2.4 Nature of the theory.

⚃ 9.4.2.5 Developmental potential.

⚃ 9.4.2.7 Dynamisms emerge from overexcitabilities.

⚂ 9.4.1 Introduction.

⚃ I created this webpage because of the series of ongoing “myths” we see concerning Dąbrowski and his theory. This page will highlight the major examples. Unfortunately, these are not trivial issues—and are important to address. There is a parallel here with the work of Maslow ( see note 1 at bottom ).

⚃ Note: I pronounce the names of these individuals based on

the way they introduced themselves to me.

Dąbrowski: “dab BROW ski” (we often hear “DOM bros

key”)

Piechowski: “pie CHOW ski” (we often hear “pee A HOS

key”)

⚂ 9.4.2 Myths.

⚃ 9.4.2.1 Self-actualization.

⚄ 9.4.2.1.1 MYTH: The higher levels in Dąbrowski

correspond to self-actualization.

REALITY: Dąbrowski rejected Maslow’s approach to

self-actualization as being unilevel. Self-actualization was introduced

into TPD by Piechowski.

Dabrowski presented a very clear view of

advanced development.

Personality, in the context of the

theory of positive disintegration, is a name given to an individual fully

developed, both with respect to the scope and level of the most essential

positive human qualities; an individual in whom all the aspects form a

coherent and harmonized whole, and who possesses, in a high degree, the

capability for insight into his own self, his own structure, his

aspirations and aims (self-awareness). It is one who has the conviction of

having found his ideal, and that his aims are of essential and lasting

value (self-affirmation), and who is conscious that his development is not

complete and therefore he is working internally on his own improvement

(education-of-oneself and self-perfection). … Personality can be

described as a self-aware, self-chosen, self-affirmed, and selfdetermined

unity of essential psychic qualities, of fundamental individual and

universal “essences.” With the achievement of personality these essences

continue to undergo quantitative changes but not qualitative changes.

These basic qualities or universal essences are: autonomy, empathy,

authentism, responsibility. The individual essences (qualities) are: (a)

exclusive, unique, unrepeatable relationships of love and friendship; (b)

consciously realized, chosen and realized primary interests and talents;

(c) self-awareness of the history of one’s own development and

identification with this awareness. … Personality is thus the aim

and the result of development through positive disintegration. The main

agents of this development are the developmental potential, the conflicts

with one’s social milieu, and the autonomous factors (especially the

third factor)” (Dąbrowski, 1972, pp. 180-181).

⚃ 9.4.2.2 Gifted.

⚄ 9.4.2.2.1 MYTH: TPD is a theory of the gifted. Today, we

see many representations that suggest Dąbrowski developed the theory

by the study of gifted children, that all gifted children fall under the

umbrella of the theory, and that overexcitability is a trait of the

gifted.

REALITY: Dąbrowski

primarily

worked with and studied mental patients. He also studied exemplars of

development. Although many of the cases looked at by Dąbrowski

involved gifted youth, he only reported one study of the gifted (see

Dąbrowski, 1967, pp. 249-262).

Dąbrowski’s conclusions:

“All gifted children and young people display symptoms of increased

psychoneurotic excitability, or lighter or more serious psychoneurotic

symptoms. … 2. In general the presence of all-around interests in

children and young people coincides with complicated forms of

psychoneurosis, with psychoneuroses of higher hierarchical system of

functions (psychasthenia, anxiety neurosis, obsessive neurosis) or with a

higher level of the same kind of neurosis” (Dąbrowski, 1967,

pp. 260-261).

In summary, the TPD has applicability to the

gifted field but is not

primarily

a theory of the gifted, nor is it based on the study of the gifted.

⚄ 9.4.2.2.2 MYTH: We can have confidence in the results of

the research on overexcitability.

REALITY: Over the last 40 years, several different instruments have

been used to measure overexcitability. It appears that these instruments

lack construct validity—does the test measure the construct as the

theory described it. Dąbrowsk described each of the five

overexcitabilities on each of the different levels (he generally did not

give examples of level V), and it is clear that a multilevel approach to

measuring overexcitability is required. Dąbrowski emphasized that

differences between higher and lower levels of a given overexcitability

are great. Unfortunately, thus far, testing approaches have not been able

to capture this degree of complexity in measuring the levels of

overexcitability.

Let’s look at emotional

overexcitabilities as an example (Falk et al. 1999). Here is what the

current questionnaire (the OEQ II) addresses:

►I feel other people’s feelings

►I worry a lot

►It makes me sad to see a lonely person in a group

►I can be so happy that I want to laugh and cry at the same time

►I have strong feelings of joy, anger, excitement, and despair

►I am deeply concerned about others

►My strong emotions moved me to tears

►I can feel a mixture of different emotions all at once

►I am an unemotional person

►I take everything to heart (pp. 7-8).

Let’s compare that to

Dąbrowski’s (1996, pp. 76-77) description:

EMOTIONAL OVEREXCITABILITY

Level I

Aggressiveness, irritability, lack of inhibition, lack of control, envy,

unreflective, periods of isolation, or an incessant need for tenderness

and attention, which can be observed, for instance, in mentally retarded

children.

Level II

Fluctuations, sometimes extreme, between inhibition and excitation,

approach and avoidance, high tension and relaxation or depression, syntony

and asyntony, feelings of inferiority and superiority. These are different

forms of ambivalence and ambitendency.

Level III

Interiorization of conflicts, differentiation of a hierarchy of feelings,

growth of exclusivity of feelings and indissoluble relationships of

friendship and love. Emotional overexcitability appears in a broader union

with intellectual and imaginational overexcitability in the process of

working out and organizing one’s own emotional development. The

dynamisms of spontaneous multilevel disintegration are primarily the

product of emotional overexcitability.

Level IV

Emotional overexcitability in association with other forms becomes the

dominant dimension of development. It gives rise to states of elevated

consciousness and profound empathy, depth and exclusivity of relationships

of love and friendship. There is a sense of transcending and resolving of

one’s personal experiences in a more universal context.

⚄ 9.4.2.2.3 MYTH: Intellectual overexcitability can be

equated with high intelligence.

REALITY: Intellectual overexcitability is not the same thing as

measured intelligence. It represents a strong desire to learn, a need to

learn, and, or a strong curiosity, not intelligence per se.

INTELLECTUAL OVEREXCITABILITY

Level I

Intellectual activity consists mainly of skillful manipulation of data and

information (“a brain like a computer”). Intelligence rather than

intellectual overexcitability serves as an instrument subservient to the

dictates of primitive drives.

Level II

The functions of intelligence become uncertain and at times suspended by

greater emotional needs. Internal opposition, ambivalences and

ambitendencies create a fair chance of disconnection of the linkage

between intelligence and primitive drives. This creates the possibility of

incipient opposition against the ruling power of primitive instincts. Such

an opposition, in the course of progressing development, creates the

possibility of multilevel internal conflicts.

We observe erudition which can be extensive and brilliant but without

systematization and evaluation of knowledge, there is no felt necessity to

penetrate into the meaning of knowledge, to analyze in order to uncover

the “hidden order of things,” or to arrive at a deeper synthesis.

Exceptional abilities in many fields can be, nevertheless, one-sided.

Level III

Intellectual overexcitability intensifies the tendency toward inner

conflicts and intensifies the activity of all dynamisms of spontaneous

multilevel disintegration. It enhances the development of awareness and of

self-awareness. It develops the need for finding the meaning of knowledge

and of human experience. Conflict and cooperation with emotional

overexcitability. Development of intuitive intelligence.

Level IV

Intellectual overexcitability in close linkage with emotional and

imaginational operates in a united harmony of drives, emotions, and

volition. The DDC is more closely unified with personality (the level of

secondary integration). Intellectual interests are extensive, universal,

and multilevel. Great deal of interest and effort in objectivization of

the hierarchy of values. Inclinations toward synthesis.

Intellectual-emotional and intellectual-emotional-imaginational linkages

are the basis of highly creative intelligence.

⚄ 9.4.2.2.4 MYTH: High (

very

high) intelligence is required for development.

REALITY: Nixon (2005, p. 5) stated: “Dąbrowski reports

that for all the children he examined who had both general and special

abilities, the lowest I.Q. score was 19.4. This would suggest that an I.Q.

at or above 110 meets the level required for personality development in

TPD.”

⚄ 9.4.2.2.5 MYTH: Research has demonstrated that gifted

children have strong overexcitabilities.

REALITY: For a balanced overview, see: MacEachron, D. (2018, June

13). Giftedness and overexcitabilities: Part 8 of Myth Busters:

Alternative therapies for 2e Learners.

https://drdevon.com/giftedness-and-overexcitabilities-part-8-of-myth-busters-alternative-therapies-for-2e-learners/

PDF version.

Pyryt (2008) concluded: “Gifted individuals are more likely than

average-ability individuals to show signs of intellectual

overexcitability. [According to TPD] This will be predictive of

higher-level potential when combined with emotional overexcitability and

higher-level dynamisms. There is limited evidence to suggest that gifted

individuals possess these components to a greater degree than

average-ability individuals.”

⚄ 9.4.2.2.6 MYTH: Overexcitabilities can be used to

identify giftedness.

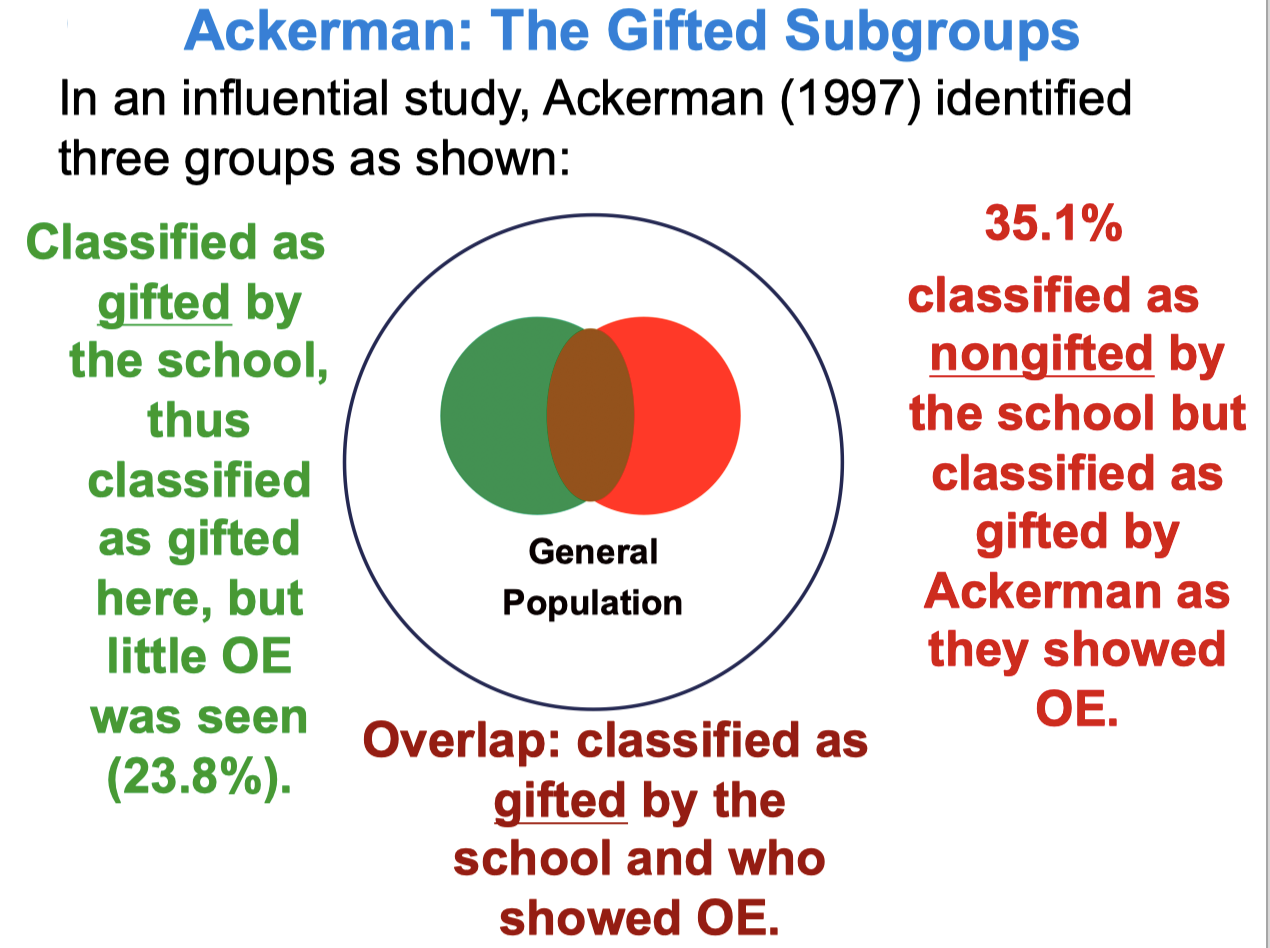

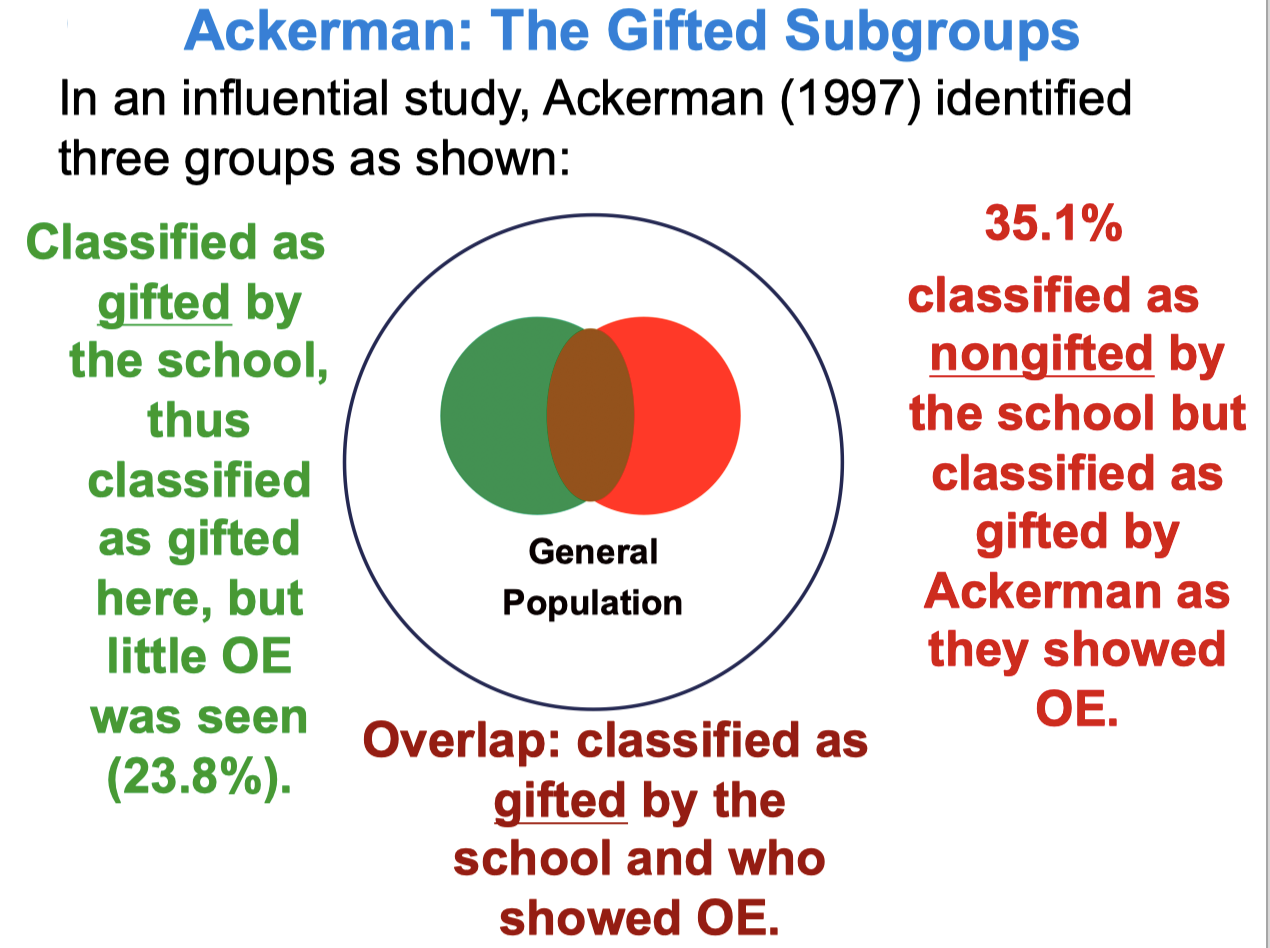

REALITY: As

Ackerman (1997, p. 233)

stated: “Classificatory analysis performed at the end of the

discriminant analysis indicated that a total of 70.9% of all subjects were

correctly classified using psychomotor, intellectual, and emotional OE

scores; that is, into the groups the schools had placed them. However, 23

subjects were classified incorrectly: 13 of the 37 (35.1%) nongifted

subjects were classified as gifted and 10 of the 42 (23.8%) gifted

subjects were classified as nongifted.” As to this last group,

Ackerman concluded that the school had misclassified them; they actually

ought to have been classified as gifted. It would seem, based on

subsequent research that has accumulated over the years, that there is not

a strong relationship between the five overexcitabilities and being

gifted, and therefore measures of overexcitability should not be used to

make inferences about being gifted or not gifted.

⚄ 9.4.2.2.7 MYTH: Dąbrowski has made a major impact

in the gifted field.

REALITY: Major handbooks in the gifted field do not refer to

Dąbrowski (and never have). A quote by McEachern (2018) illustrates

the issue: “[This makes me wonder why] the gifted community has been

so dogmatic about its belief in overexcitabilities, despite the lack of

empirical evidence. It may be that people decided they liked the idea when

it was just a hypothesis and haven't kept up with the research findings.

It was striking how fast thought-leaders in the gifted community jumped on

the wagon when the hypothesis was first popularized in the 1980’s,

despite a near total lack of any evidence at the time. I think it could

also be due to the ‘halo effect.’ Professionals in the gifted

community want to see the people they work with through a positive lens.

For parents, the idea that their child is oversensitive as part of their

giftedness and that’s a good thing may be more appealing than an

additional diagnosis of AHDH or Asperger’s or anxiety. Finally, we

all want to think that pain and suffering will prove, in the long run, to

be for the best. We want to believe it, and so we do.”

⚃ 9.4.2.3 Levels.

⚄ 9.4.2.3.1 MYTH: Level I consists of only a handful of

psychopaths.

REALITY: Dąbrowski described a continuum at level I. At the

lower sub-level, psychopaths who are incapable of development exist

(“moral dwarfs”). At the mid-level is the average person. At

the higher sub-level are people who display some psychoneurotic elements.

Level I is also characterized by a continuum of integration: the extreme

rigid integration of the psychopath and the strong integration of the

average person. Those with psychoneurotic elements show weaker integration

and may slip back and forth into level II (depending on their level of

developmental potential). The alternative view is promoted by Piechowski.

⚄ 9.4.2.3.2 MYTH: Level II contains the average person,

and disintegration is not a major factor.

REALITY: Dąbrowski described level II as being a transitional

level characterized by its name—unilevel disintegration. This is a

level of extreme stress and confusion. The individual does not have a

clear view of what they want and therefore displays ambivalence: one

choice is as good as the other (and they are both

horizontal

choices). The individual is also characterized by

ambitendencies—they are drawn to one alternative and then another

and tend to go back and forth. The alternative view is promoted by

Piechowski.

⚄ 9.4.2.3.3 MYTH: We can have a good healthy (and moral)

society of unilevel individuals.

REALITY: Reflecting Plato’s approach, Dąbrowski was clear

that the goal of both individual and societal development ought to be the

rich, deep, and nuanced experience described by multilevelness. Through

his writings we can see he fundamentally believed that both individual and

societal development must reflect autonomy and authenticity: qualities

that can only be derived by multilevel development. This development

emphasizes an internal locus of control that supersedes the impact of the

environment and either supersedes or transforms lower impulses. The

individual’s morality must come from within and be based upon a

uniquely developed hierarchy of values reflecting the individual’s

essence. The alternative view is promoted by Piechowski.

⚃ 9.4.2.4 Nature of the theory.

⚄ 9.4.2.4.1 MYTH: Dąbrowski’s theory is about

emotional development.

REALITY: Dabrowski said that he could not find a psychological

theory that could adequately explain both the lowest and highest levels of

behavior that he had observed in his lifetime. He was also intrigued by

exemplary personalities and how their development occurred and differed

from that of the average person. In discussions, Dąbrowski presented

the theory as one of personality development.

The theory is not about emotional

development

per se

. Here, emotional development parallels and occurs in tandem with

psychological and personality development. Emotions in the theory change

and are transformed with development. For example, at the lowest levels,

emotions reflect primitive ego states; I am mad because I didn't get the

promotion. I am jealous because my wife looked at another man. I am

envious because my neighbor got a new car. At the average level of

development, emotions largely reflect social expectations and syntony. I

cry at funerals because that’s what I’ve learned people do. I

laugh at jokes around the water cooler because the people beside me laugh

(“primitive syntony”). I'm sad when my parents are mad at me

because I want them to love me and give me things and their attention.

These are unilevel emotions.

If overexcitability and other developmental

potentials are present, then these will impact emotional development and

expression. As the personality develops, emotions take on a different role

and expression as they become multilevel. Emotions shift to an internal

locus of control and become less dependent on the environment. I may be at

my birthday party, and everyone is happy, but I feel sad because of what I

saw on the news last night.

The development of the inner psychic milieu

allows more volitional control in organizing emotions and developing a

hierarchy of higher and lower emotions. Multilevel emotions reflect

self-awareness and a growing degree of objectivity of the self as

subject-object develops. At the highest levels, emotions become exclusive;

for example, unique feelings of love develop for a partner. Emotional

overexcitability influences the expression of intellectual and

imaginational and takes a dominant role in organizing one’s

emotional expression.

Dąbrowski said that at the highest

levels, emotions and values become synonymous. One’s hierarchy of

values becomes a unique expression of one’s character, expressed

through one’s emotions. A synthesis occurs by bringing together

personality ideal, the third factor, one’s values, one’s

intuitive intelligence, and one’s imagination and emotions. At this

high-level, self-education and autopsychotherapy are important components

in managing and maintaining self-development.

Finally, Dąbrowski integrated emotions

into his definition of dynamism: DYNAMISM. Biological or mental force

controlling behavior and its development. Instincts, drives, and

intellectual processes combined with emotions are dynamisms.

In summary, emotions play a critical role in

most aspects of the theory. Still, the focus of development in the theory

is on the overall personality development of the individual.

⚄ 9.4.2.4.2 MYTH: Dąbrowski’s theory is about

moral development.

REALITY: As with emotion above, the theory is not about moral

development

per se

. Morality and values reflect the level of one’s development. At the

lowest level, there really is no sense of morality or values, and

Dąbrowski refers to these individuals as “moral dwarfs.”

At the average level of development, the individual reflects and rotely

recites the values and morals of their social environment; the second

factor. Values are interiorized with little examination or evaluation. As

multilevelness develops, a shift inwards occurs. The development of the

inner psychic milieu provides a framework for creating a self-created and

autonomous hierarchy of values. A unique and autonomous morality

reflecting an individual’s deep essence and character emerges.

⚄ 9.4.2.4.3 MYTH: Dąbrowski’s theory is all

about overexcitabilities

REALITY: The theory of positive disintegration is a broad and

complex network of constructs. Overexcitability is a component of

developmental potential, an important part, but certainly not “the

whole picture,” either in terms of developmental potential or of the

overall theory. Overexcitability acts in the theory in conjunction with

other developmental potentials, for example, the third factor and, as

well, the dynamisms. Overexcitability acts in conjunction with

psychoneuroses to create disintegration. The expression of

overexcitabilities depends on the level of development—thus, the

multilevel aspects of the individual case need to be evaluated and taken

into account. Each overexcitability has different expressions on each of

the five levels creating 25 descriptions. It should be kept in mind that

overexcitabilities are a necessary but not sufficient condition for

advanced development to occur.

⚄ 9.4.2.4.4 MYTH: We don't need to suffer or disintegrate

to grow.

REALITY: Dąbrowski assigned several important roles to the idea

of suffering and disintegration. First, in his theory, unilevel

integration inhibits individual autonomy and growth. This initial

integration must break down to allow the locus of control to shift from

the environment and lower instincts to the volitional control of the

individual. This marks the beginning of true autonomous development.

Individual development does not occur spontaneously—the self must be

constructed. The personality ideal must be developed. The hierarchy of

values must be created by the individual. These constructions do not

happen under the conditions of unilevel integration. Next. Dąbrowski

felt that through the process of subject-object we could come to see the

inevitable suffering that life brings us in a different context. Rather

than feeling anger or resentment that we have suffered, subject-object

allows us to see others and appreciate their suffering, giving us a

perspective that our situation is often not as dire as we think. It gives

us humility and seeing that others have it worse, giving us strength to

carry on. It gives us empathy and compassion for others. Piechowski has

suggested that the role of suffering in growth is greatly exaggerated by

Dąbrowski in TPD due to his own personal and harsh life experiences.

⚄ 9.4.2.4.5 MYTH: TPD and Dąbrowski are (were)

anti-psychiatry.

REALITY: Dąbrowski recognized traditional psychiatric diagnoses

and advocated their treatment with conventional psychiatric medication.

For example, schizophrenia. He felt that the average person should utilize

traditional psychotherapy when necessary. For people with multilevelness

he advocated what he called autopsychotherapy. Unfortunately, the book

manuscript describing autopsychotherapy has only been seen by a handful of

people in North America.

⚄ 9.4.2.4.6 MYTH: “Mendaglio and Tillier see the

theory as

cast in stone and invariable: Dąbrowski’s ‘choice of

terms and their definitions cannot be a focus of criticism: after all,

TPD is his theory.’ Consequently, Mendaglio and Tillier blindly

stand by even the most absurd, inadvertently erroneous statements that

are contradicted by the whole theory.”

(Dąbrowski Centre website February 2023)

REALITY: Mendaglio and I recognize that the extensive nomological

network of constructs developed by Dąbrowski constitutes a broad

theory of how personality develops. Many of these constructs are tentative

hypotheses that await verification. Obviously, as more data is gathered,

hypotheses will be changed, added, or perhaps deleted altogether. This is

a routine and regular part of theory building and development that we both

look forward to. Traditionally, as theories are superseded, the name

associated with the original theory stands, and the name of the subsequent

contributor(s) characterizes the new theory. For example, Ptolemy’s

astronomical model was superseded by Nicolaus Copernicus' heliocentric

model (the Copernican system), which was superseded by the model described

by Tycho Brahe (the Tychonic system). Thus, Dąbrowski’s name

will always be associated with the theory he proposed. No one has yet

offered a substantial replacement for the theory. When someone does,

let’s say, Elmer Fudd, it will rightfully be called “The

Fuddian Theory

of positive disintegration.”

.

⚃ 9.4.2.5 Developmental potential.

⚄ 9.4.2.5.1 MYTH: Developmental potential is not genetic.

REALITY: Dąbrowski conceptualized developmental potential as

genetic. He compared it to intelligence. Although the environment may

enhance or stunt intelligence, the fundamental basis of intelligence is

genetic. The alternative view is promoted by Piechowski.

The first of these factors involves

the hereditary, innate constitutional elements which are expressed in the

developmental potential, in a more or less specific way, and are already

recognizable in a one year old child” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 33)

Primary loosening or breakdown of

psychic functions and psychic structure is largely determined and

catalyzed by hereditary nuclei (as increased excitability, nuclei of the

inner milieu, nuclei of creative interests and abilities), which slowly

introduce the dynamisms of higher level, such as transformative abilities,

hierarchy in adjustment and maladjustment (positive maladjustment)”

(Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 82)

⚄ 9.4.2.5.2 MYTH: All that really counts is having

overexcitabilities.

REALITY: Dąbrowski described developmental potential as

involving far more than simply overexcitability. Other factors include;

instincts, dynamisms, abilities and talents, and the third factor, to list

the main ones. The process of development also requires psychoneuroses

acting in concert with specific developmental potentials.

⚄ 9.4.2.5.3 MYTH: All that really counts is having strong

developmental potential.

REALITY: Dąbrowski was very clear that even with very strong

developmental potential growth is not a given. Growth does not occur

automatically or without conscious and volitional input. Developmental

potential is necessary but not sufficient for growth. One must develop

one’s inner psychic milieu and be able to bring the dynamisms of

development under conscious management. These include the third factor.

Dąbrowski’s number one concern was always suicide precipitated

by the stresses of development, and he emphasized that navigating

“the dark night of the soul” is an existential challenge that

not everyone can surmount.

⚄ 9.4.2.5.4 MYTH: Overexcitabilities are just intense

excitabilities.

REALITY: Overexcitabilities are not just

being excited

or

hyper. First, to be developmental they require management to inhibit, control,

and direct their energy in positive ways. Without any management, they

tend to be simply disruptive or disorganizing and sometimes may border on

hypomania. Dąbrowski (undated and unpublished manuscript) emphasized:

“What is increased psychic excitability or so-called nervousness? We

could describe it in general terms as the increased sensitivity toward the

multilevelness of reality. It is our excessive, stronger than normal,

reactivity to external and internal stimuli, in which the reactions are

long-lasting and create strong engrams as well as easily undergo

ecphory.” Here we see two critical psychological impacts of

overexcitability. First, they give us a deeper and more nuanced view of

reality. This contributes to the development of vertical conflicts: an

important component of disintegration. Second, they contribute to a more

comprehensive memory and to a more sensitive memory. Increased ecphory

means that memories can be more easily retrieved based on various cues.

When overexcitability (usually confined to

psychomotor and sensual) distinctly dominates nervous activity, such that

there is little or no inhibition or no conscious control, the indication

is Level I. When overexcitability (usually including emotional) is

accompanied by inhibition, but without conscious control, the indication

is Level II. When inhibition distinctly dominates nervous activity giving

rise to great and pervasive tension, but with little or no conscious

control, the indication is the borderline between Levels II and III. When

overexcitability and strong inhibition appear concurrently or

simultaneously, with some conscious control, the indication is Level III.

The distinct predominance of conscious control, in the presence of

overexcitability and inhibition, indicates the borderline between Levels

III and IV, or higher.

The five forms of overexcitability are

ordered in terms of increasing importance for development: psychomotor,

sensual, intellectual, imaginational, emotional. In particular cases, it

is necessary to know the forms and extent of overexcitability. For

example, even when overexcitability pervasively dominates over inhibition,

if emotional overexcitability is present, the level diagnosis is higher.

The kind and form of inhibition is also important in particular cases, for

example, uniform and indiscriminate inhibition of all forms of

overexcitability including higher forms, is less positive than selective

inhibition of lower forms, which shows some conscious control”

(Dąbrowski & Piechowski, 1996, p. 186).

⚄ 9.4.2.5.5 MYTH: Overexcitability can be used as an

independent construct without reference to the theory.

REALITY: The overexcitabilities, as described by Dąbrowski, are

interrelated and work in concert with several other vital constructs. For

example, they work together with developmental dynamisms and the third

factor to help transform conflict into growth. To view them as a

standalone construct removes them from the context of the overall theory

and this would impact their theoretical understanding, and in tern, this

will impact how the construct is used in research.

⚄ 9.4.2.5.6 MYTH: The five overexcitabilities are

independent variables and can be used in research as such.

REALITY: The five overexcitabilities arise from underlying

developmental potential. If you have enough development potential to

produce an overexcitability, you will likely have more than one. They do

not exist or act in isolation from each other and, therefore, cannot be

considered independent variables according to the theory.

⚃ 9.4.2.6 Michael Piechowski.

⚄ 9.4.2.6.1 MYTH: Michael Piechowski “wrote TPD

with

Dąbrowski – they developed the theory together.”

REALITY: Several authors have written that Dąbrowski &

Piechowski somehow co-wrote or developed the theory together. This is not

the case. Piechowski acted as translator and assisted in editing but did

not contribute any constructs to the theory.

⚄ 9.4.2.6.2 MYTH: Michael Piechowski has not received

proper credit for the work he contributed to Dąbrowski’s

publications.

REALITY: Dąbrowski was careful in his attributions, and I have

carefully checked how Piechowski has been credited. I do not see an

instance where his contribution was not acknowledged. If there is a

concern, please bring it to my attention. Piechowski has told me he feels

that “based on the number of hours he contributed, he should have

been given co-authorship of volume 1 of the 1977 books” and

Dąbrowski disagreed. Further, the figures and tables in the 1972 book

are attributed in the acknowledgments section. I understand Michael left

Edmonton as he sought greater input into the works and Dąbrowski

would not allow it.

⚄ 9.4.2.6.3 MYTH: “Tillier’s issues simply

reflect a personal issue he has with Piechowski.”

REALITY: Anyone who knows me knows that I have a strong loyalty

to Dąbrowski and his theory for what they have given me in my life. I

am also acutely aware of the tremendous needs many people have today and

the potential of the approach of positive disintegration to help at least

a segment of these people. I am very sad and concerned that, over the past

40 years, the theory has not had the benefit of clear, original, and

complete presentations in the literature and appears to have suffered

“a wrong turn on the road.” For me, this is a matter of

academic integrity and the future of the theory—the stakes are the

life or death of the theory. I am not alone in my concern; many people

feel the same way.

In 1976 I met and began attending lectures

by Dąbrowski. Christmas, 1977, I met Michael Piechowski. Over the

years, I had many cordial discussions with Michael, including him spending

the weekend with me at my home. Again over years, Michael and I became

less communicative as he became frustrated that I would not alter my

position—I supported the original views of Dąbrowski and

confronted Michael about the way he presented Dąbrowski’s

ideas. Michael presented the theory in such a way that the reader

unfamiliar with Dąbrowski had a challenge knowing what material

reflected Dąbrowski’s original position and what material

reflected Michael’s interpretations. I urged him many times to

clearly differentiate his views from Dąbrowski’s, and he

refused, saying, “I'm not offering my own theory theory; I am simply

correcting mistakes Dąbrowski made.”

From 1980 to 1994, Norbert Duda was the

public face advocating for the fidelity of Dąbrowski’s theory.

He attended many workshops and spoke up. In 1994, Sharon Lind organized

the Keystone Colorado workshop, and, after attending that, I took on a

public role along with Norbert. I created the website in 1995, and I

organized the next conference in Canada in 1996.

Over the past 40 years, people have

primarily seen TPD linked only to overexcitability and to the gifted.

Michael’s ideas had a major impact on shaping how the theory was

perceived and understood. Initially, the original materials of

Dąbrowski were difficult to obtain and readers relied upon

Piechowski’s publications to learn the theory. Readers were left to

judge the theory of positive disintegration solely upon the basis of

overexcitability as measured in the gifted population. Again, over the

years, accumulating research results have not supported a strong

association between the five overexcitabilities and the gifted population.

Thus, today, many in the gifted field now reject Dąbrowski’s

work

in toto.

Unfortunately, today, some people seem to

gloss over the differences between the two authors and even consider them

insignificant. Others appear to endorse Piechowski’s views,

preferring them to Dąbrowski’s original, as they are more

accessible and easier to understand.

I fully endorse orderly research and

development of the TPD. However, the only way for the theory to develop

and grow is for challenges and alternatives to be presented so that the

reader can compare and contrast different versions, along with future

research evidence. This would eventually lead to neo-Dąbrowskian

formulations.

For example, the work of Aron on HSP

individuals has had a great impact — it has become a

popular theory in the public realm and has also had an impact on academic

psychology. The two theories seem to share some major similarities, but as

well, some major differences. Aron’s approach to sensitivity and

strategy for dealing with heightened sensitivity is quite different from

Dąbrowski’s and she does not link heightened sensitivity to any

sense of growth or positivity. It would be worthwhile for both theories to

be carefully compared and contrasted and consider the implications of

their similarities and differences.

⚃ 9.4.2.7 MYTH: Dynamisms emerge from overexcitabilities. “The dynamisms are actually the products of certain types and combinations of overexcitabilities” (Piechowski & Wells, 2021, p. 78).

REALITY: The idea that the dynamisms are produced by overexcitabilities was first presented by Piechowski in 1975 as a hypothesis.

Quote: If we accept the hypothesis that dynamisms differentiate from forms of overexcitability, then these forms take on the role of primary factors of development. Thus the theory of positive disintegration offers the means by which one can account for developmental transformations in the level of cognitive and emotional behavior. (p. 294)

Additional context: In 1970, Dąbrowski wrote a manuscript that was subsequently revised in 1972 and 1974. Those manuscripts evolved, and Michael Piechowski was involved in their revisions. In 1977, Michael used those manuscripts as a basis for the 1977 books that were published by Dabor Science Publishing. Those published books had major changes, and Dąbrowski did not acknowledge them, instead saying that he wanted to revise the manuscripts and have them republished. Dąbrowski never had a chance to revise them, and they were republished in 1996. Unfortunately, this was one of the theoretical issues that reflected Michael’s position and not Dąbrowski’s.

Quote: If we accept the hypothesis that dynamisms differentiate from forms of overexcitability, then these forms take on the role of primary factors of development. Thus the theory of positive disintegration offers the means by which one can account for developmental transformations in the level of cognitive and emotional behavior. (Piechowski, 1975, p. 294)

Later, this idea is presented as a descriptive fact:

Quote: Multilevel development emerges from strong overexcitabilities, as well as other aspects of what Dabrowski called developmental potential, including special talents and abilities and dynamisms. The dynamisms are actually the products of certain types and combinations of overexcitabilities. (Piechowski, & Wells 2021, p. 78).

In Dąbrowski’s description developmental instincts and dynamisms come before overexcitabilities. This also makes conceptual sense because Dąbrowski defines dynamisms as emotions and instincts (see Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 167), and it is difficult to see how emotions and instincts could be products of overexcitabilities. I think it’s important that this be known, as these misunderstandings continue to appear in the literature, for example, in Mendaglio’s 2024 book.

Supporting quotes: In describing dynamisms, Dąbrowski was clear that instincts and emotions are critical aspects:

“The various dynamisms presented here in their structure, action, and transformations we also call instincts. Our reason for including these forces among instincts is that, in our view, they are a common phenomenon at a certain level of man’s development, they are basic derivatives of primitive instinctive dynamism, and their strength often exceeds the strength of the primitive maternal instinct” (Dąbrowski, 1967, p. 54).

“DYNAMISM, biological or mental forces of a variety of kinds, scopes, levels of development and intensity, decisive with regard to the behavior, activity, development or involution of man. Instincts, drives and intellectual processes conjoined with emotions constitute specific kinds of dynamisms” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 167).

Dąbrowski is clear that instincts – dynamisms and overexcitabilities are both genetic attributes that we were born with; one does not emerge from the other.

⚂ Note 1: The two major “myths” of Maslow’s theory are:

MYTH: Self-actualization is the apex of development.

REALITY: Maslow was clear that self-transcendence was the apex of

development.

For example: Maslow, A. H. (1969). Various meanings of transcendence.

Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 1

(1), 56-66.

Maslow, A. H. (1976).

The farther reaches of human nature.

Penguin. (Original work published 1971)

MYTH: Maslow used a pyramid to depict his levels.

REALITY: Maslow never used the illustration of a pyramid in his work.

Bridgman, T., Cummings, S., & Ballard, J. (2019). Who built Maslow’s pyramid? A history of the creation of management studies' most famous symbol and its Maslow implications for management education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 18 (1), 81-98. Bridgman2019.pdf.

![]()