⚂ Dąbrowski saw a correlation between personality development and

special abilities and talents, a component of developmental potential.

≻ Dąbrowski said that a minimum IQ of 110 was necessary but not sufficient for mental development (see Nixon 2005).

≻ He developed the hypothesis that those with exceptional abilities

and talents – the gifted – would display

significant developmental potential including overexcitability.

≻ He also hypothesized these individuals should display neuroses and

psychoneuroses, the hallmarks of the process of positive disintegration

and hence, eventually, advanced personality development.

⚃ The TPD is not based on the study of gifted individuals. As far as we can see, Dąbrowski conducted only two studies with “gifted” children:

⚄ One, reported in Dąbrowski (1967) and again in (1972).

⚅ Examined 80 children: 30 “intellectually gifted” and 50 from “drama, ballet and plastic art schools” (Dąbrowski, 1967, p. 251).

⚅ Found “every child” showed “hyperexcitability,” various psychoneurotic symptoms and frequent conflicts with the environment.

⚅ “The development of personality with gifted children and young people usually passes through the process of positive disintegration” (Dąbrowski, 1967, p. 261).

≻ This hypothesis has not yet been tested.

⚄ The second study: “Psychiatric examinations of 170 normal children carried out in public schools, schools of fine arts, and the Academy of Physical Education, by the Institute of Mental Hygiene and the Children’s Psychiatric Institute in Warsaw have shown that about 85% of the subjects with I.Q. from 120 to 150 have various symptoms of nervousness and slight neurosis, such as mild anxiety, depression, phobias, inhibitions, slight tics and various forms of overexcitability” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 18).

⚂ In the manuscript, On Authentic Education, Dąbrowski said: “The nervous and psychoneurotic individual is present in an overwhelming percentage of highly gifted children and youths, artists, writers, etc. [The] tendency to reach beyond the statistical norm and mediocre development presents the privilege and drama of psychoneurotic people” (p. 50).

⚃ “The extremely sensitive child, in contact with conflict in everyday life (with death and injustice), and the child who deeply experiences feelings of inferiority can develop, in spite of his intellectual gifts, anxiety psychoneurosis: be afraid of darkness, loneliness and aggressiveness in others” (p. 59).

⚂ Dąbrowski’s hypotheses: as a group, students identified as gifted will tend to display stronger DP (and OE), increased levels of psychoneuroses, and will be predisposed to experience positive disintegration.

⚃ Many students should display “symptoms” that may reflect higher potentials.

⚃ May display unusual sensitivity, frequent crises, anxieties, depression, perfectionism, etc.

⚃ May express strong positive maladjustment:

⚄ Strong sense they are different, don’t fit in.

⚄ Have conflicts with social (unilevel) morality.

⚄ Feel alienated from others, from their peers.

⚄ Significant potential for self-harm and suicide.

⚂ The application of the TPD to the field of the gifted began

with Piechowski’s introduction of overexcitability as a feature of

gifted children (Piechowski, 1979).

≻ This publication stimulated a flurry of subsequent work in the

gifted field specifically looking at overexcitability, one component of

Dąbrowski’s concept of developmental potential.

⚃ Piechowski developed the OEQ test of OE (not a test of full DP) (Lysy & Piechowski, 1983).

⚃ Ackerman (1997b) found problems with the OEQ:

⚄ A revised test, the OEQ-II, was developed (Falk, Lind, Miller, Piechowski, & Silverman, 1999).

⚂ OE was popular because parents easily related and research was aided by having the OEQ and OEQ-II.

⚂ Over the past 40+ years, many research projects and papers have addressed OE, most in the context of gifted populations (see Mendaglio & Tillier, 2006).

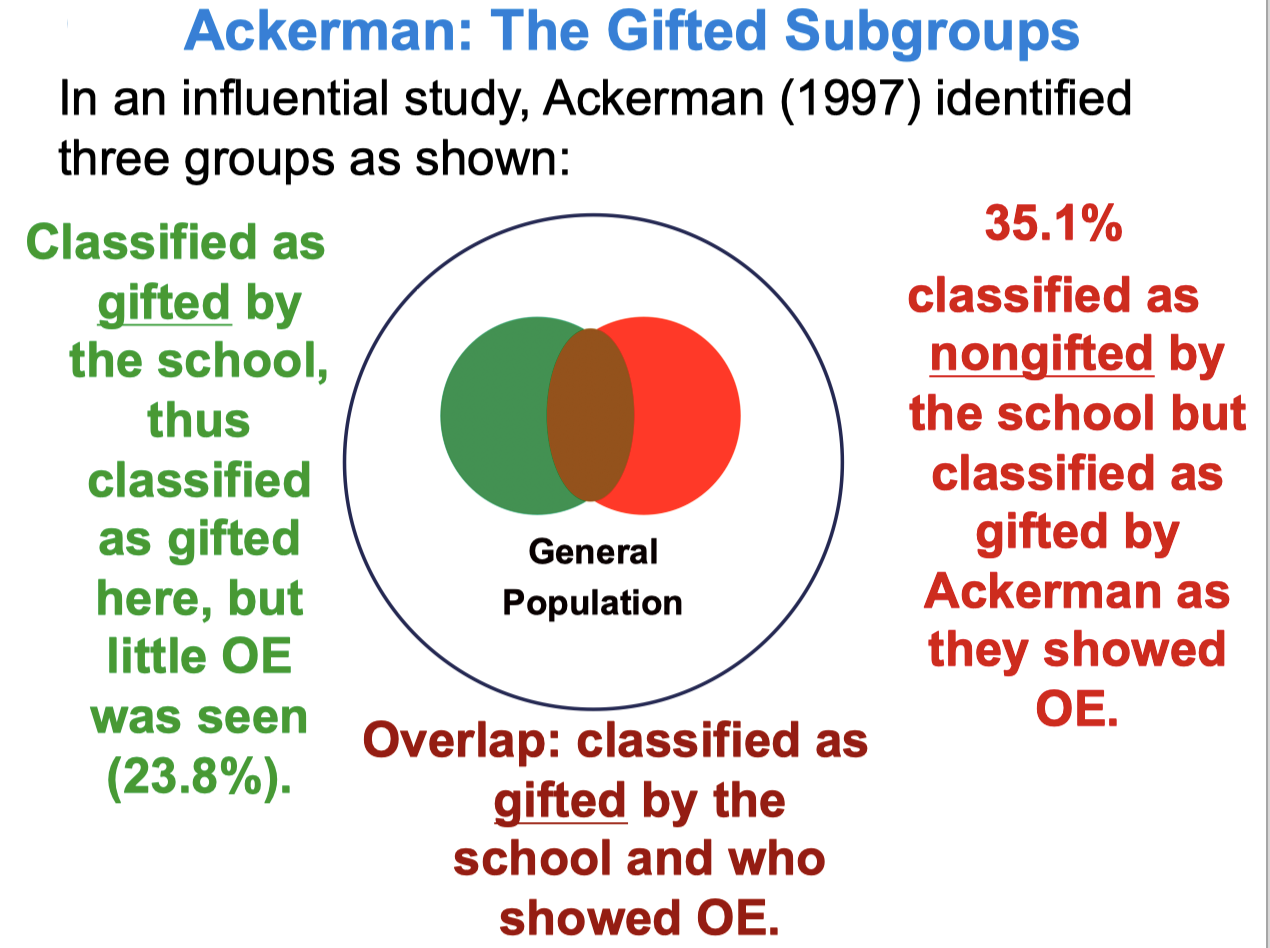

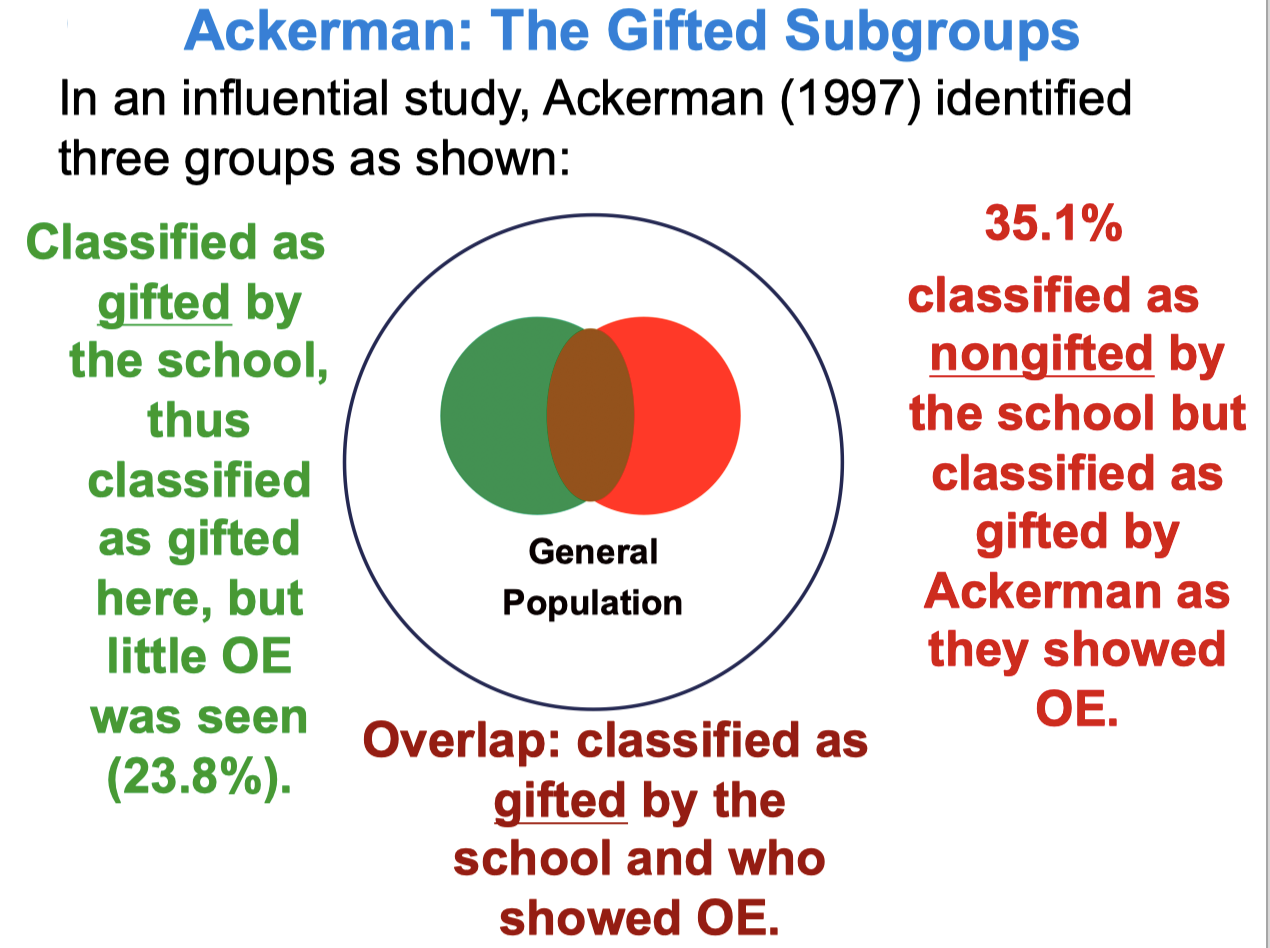

⚂ Ackerman (1997a): The gifted subgroups.

⚃ In an influential presentation, Ackerman (1997a) reported the results

of her study of 79 students using Piechowski’s overexcitability

questionnaire.

≻ Total sample 79.

≻≻ Numbers as classified by school:

≻≻≻ Gifted 42 (53%) – 32 gifted with overexcitability [40% of 79] + 10 gifted without overexcitability [13% of 79]

≻≻≻ Not gifted 37 (47%) – 24 not gifted without overexcitability [30% of 79] 13 not gifted with overexcitability [17% of 79]

≻≻ Numbers as classified by Ackerman:

≻≻≻ 23 (58.9%) classified “incorrectly” by school:

≻≻≻ 13 of 37 (35%) non-gifted (School) but had overexcitability and therefore must be gifted

≻≻≻ 10 of 42 (24%) gifted (School) but without overexcitability.

⚃ “Classificatory analysis performed at the end of the discriminant analysis indicated that a total of 70.9% of all subjects were correctly classified using psychomotor, intellectual, and emotional OE scores; that is, into the groups the schools had placed them. However, 23 subjects were classified incorrectly: 13 of the 37 (35.1%) nongifted subjects were classified as gifted and 10 of the 42 (23.8%) gifted subjects were classified as nongifted” (Ackerman, 1997a, p. 233).

⚃ “In the current study, 13 of the 37 (35.1%) nongifted students were classified as gifted. This suggests that there are some students in the sample that have not been identified as gifted based on their I.Q. scores, peer, teacher, and parent nominations, and school grades, although, these students have personality characteristics similar to those students who were identified as gifted. Personality characteristics in this sense refer to psychomotor, intellectual, and emotional OEs, which are included in the discriminant function coefficient. Thus, it is possible that approximately 35% of the non-gifted students could be gifted based on the classificatory analysis results.

The classificatory analysis also indicated that a number of gifted subjects were misclassified. That is, their OE profiles were more similar to the nongifted profile than the gifted profile. Of the gifted students, 23.8% (10 of 42) matched the nongifted profile more closely. Therefore, while the score on the OEQ might be able to identify some students as gifted that would not have been identified based on the methods used in their school, it should serve as an additional measure, and not a replacement for current methods.

One of the most important findings in this study was that based on OEQ scores and profiles, 35% of the nongifted subjects matched the gifted profile based on statistical analyses. This provides some support to the notion that an additional method of identification is necessary and that the Overexcitability Questionnaire could be useful for this purpose. While there were also 24% of the gifted subjects with profiles similar to that of the nongifted, this point is not as important to the current study, because these individuals would already have been identified” (Ackerman, 1997a, p. 234).

⚃ Type of overexcitability:

≻ The literature: emotional, intellectual, and imaginational – “Earlier studies, (Gallagher, 1986; Lysy & Piechowski, 1983; Piechowski & Miller, 1994; Piechowski & Colangelo, 1984; Silverman & Ellsworth, 1981), found emotional, intellectual, and imaginational OEs, in varying order, to be the highest three OEs for their gifted subjects” (Ackerman, 1997a, p. 233). [see Pyryt (2008), below]

≻ Ackerman: Psychomotor, emotional and intellectual – “Therefore, even though emotional and intellectual OEs were the highest scores and were also identified as discriminating between the two groups in the current study, psychomotor OE was identified as the OE that most differentiated between the gifted and nongifted samples” (Ackerman, 1997a, p. 233).

⚄ This report influenced the gifted field and today, many consider OE and gifted to be synonymous.

⚄ To my knowledge, the important implications of this study and the three discrete groups have not been further replicated, elaborated or researched.

⚂ Pyryt (2008) reviewed the research findings on overexcitability and

the gifted and concluded that gifted individuals are more likely than

those not identified as gifted to show signs of intellectual OE, but based

upon the research strategies and testing done to date, the gifted do not

consistently demonstrate "the big three," intellectual, imaginational and

emotional OE.

≻ Pyryt (2008) concluded, "it appears that gifted and average

ability individuals have similar amounts of emotional overexcitability.

≻ This finding would suggest that many gifted individuals have

limited developmental potential in the Dąbrowskian sense and are more

likely to behave egocentrically rather than altruistically" (p. 177).

⚂ In summary, based upon the research done to date, the relationship

between overexcitability and the gifted appears to remain unclear or

largely unsupported.

≻ The relationship between developmental potential, as

Dąbrowski described it, to the gifted remains to be tested as does

the relationship between psychoneuroses and the gifted and positive

disintegration and the gifted.

⚂ References.

Ackerman, C. M. (1997a). Identifying gifted adolescents using personality characteristics: Dąbrowski’s overexcitabilities. Roeper Review, 19 (4), 229-236.

Ackerman, C. M. (1997b). A secondary analysis of research using the Overexcitability Questionnaire. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, August, 1997, Texas A & M University, College Station, Texas. [Dissertation Abstract] Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences. Vol 58(7-A), Jan 1998, pp. 2526.

Colangelo, N. & Zaffrann, R. T. (Eds.) (1979). New voices in counseling the gifted. Kendall/Hunt.

Dąbrowski, K. (n.d.). On authentic education. Unpublished manuscript. 103 pages. With a separate 4 page preface entitled Authentic Education.

Nixon, L. (2005). Potential for positive disintegration and IQ. The Dąbrowski Newsletter, 10 (2).1-5.

Piechowski, M. M. (1979). Developmental potential. In N. Colangelo and R. Zaffrann (Eds.), New Voices in Counseling the Gifted (25-57). Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall Hunt.

Pyryt, M. C. (2008). The Dąbrowskian lens: Implications for understanding gifted individuals. In S. Mendaglio (Ed.). Dąbrowski’s Theory of Positive Disintegration (pp. 175-182). Scottsdale AZ: Great Potential Press, Inc.

![]()