Print or print to save as PDF.

3.5.1. Table of contents.

⚂ 3.5.1 Introduction and Context.

⚂ 3.5.2 Who was Kazimierz Dąbrowski?

⚂ 3.5.3 Marie Jahoda.

⚂ 3.5.4 Multilevel and Multidimensional Approach.

⚂ 3.5.5 Dąbrowski’s 5 Levels.

⚂ 3.5.6 Disintegration.

⚂ 3.5.7 Developmental Potential.

⚂ 3.5.8 Key Constructs.

⚂ 3.5.9 Emotion and Values in Development.

⚂ 3.5.10 Applications of the TPD.

⚂ 3.5.11 Applications in Education.

⚂ 3.5.12 Applications in Gifted Education.

⚂ 3.5.13 Current and Future Issues.

⚂ 3.5.14 Conclusion.

⚄ Master References: https://www.positivedisintegration.com/masterref.pdf

⚄ Another useful guide for reading Dąbrowski is Tillier (2018).

⚂ 3.5.1 Introduction and Context.

⚃ Dąbrowski’s work has never been easy to overview because there are many interrelated constructs.

⚃ Direct quotes from Dąbrowski will illustrate his ideas.

⚃ Dąbrowski used a unique “dynamic” approach: one construct has different descriptions, different functions, and different impacts at different developmental levels. This complexity is inherent in Dąbrowski’s construct of multilevelness.

⚃ Dąbrowski’s thinking was quite original and his conclusions often challenge the status quo.

⚃ Dąbrowski’s theory was shaped by diverse influences.

⚃ The real introduction to Dąbrowski remains reading his original works and seeing his ideas emerge.

⚃ 3.5.1.1 Dąbrowski’s theory.

⚄ Dąbrowski wrote a broad, interrelated and nuanced theory to account for human personality development:

⚅ He integrated many diverse streams of thought, from philosophy, from psychiatry, from psychology, from neurophysiology, and from literature.

⚅ Dąbrowski’s English works represent a sample of his overall publications (~ 2X as many in Polish).

⚅ As material is obtained and translated, more detail will emerge.

⚄ There is an intuitive element in comprehending Dąbrowski; as some have said, “it’s a theory best understood by its application in one’s life,” some who approach it academically, “just don’t seem to get it.”

⚃ 3.5.1.2 Frustrating ideas and language.

⚄ Basic contradictions: How can psychological disintegration be positive? Personality is rare. Maladjustment can be healthy.

⚄ Psychology assumes that the developmental process is universal – we all psychologically develop along the same basic path.

⚄ TPD says advanced development (and true personality) is rare and follows a non-traditional path.

⚄ It is frustrating to learn TPD because it often uses traditional words (e.g., personality) to describe ideas that are defined and used in a unique way. Also because the ideas are interrelated in a complex network: It takes time to see Dąbrowski’s “big picture.”

⚄ Many new constructs and terms are introduced.

⚄ The theory is not definitive or “black and white,” vagueness and subtlety reign. Dąbrowski explained that he was vague at times because he did not always have a full understanding. He emphasized that more research will be needed “to fill in the blanks.”

⚃ 3.5.1.3 Combination of old and new approaches.

⚄ Dąbrowski assembles old ideas in a unique way:

⚅ Subsumes a traditional Piagetian (cognitive) approach but under an emotion – based umbrella.

⚅ Places emotion in a unique guiding role.

⚄ Dąbrowski adds several new and unique constructs:

⚅ Multilevelness (ML) as a psychological view of reality.

⚅ Developmental Potential (DP) [includes several constructs].

⚅ Positive Disintegration: Initial, lower level psychological integrations are governed by lower instincts and by socialization. These “primary” integrations must break down to allow the creation of new, higher level structures.

⚃ 3.5.1.4 Philosophical and psychological approach.

⚄ The theory combines two different philosophical traditions: elements of the essentialism of Plato with the emphasis on individual choice in existentialism (called the “existentio-essentialist compound”).

⚄ Essence is primary, but it’s not enough for one’s essence to just unfold, it must also be shaped by one’s day-to-day existential choices.

⚄ Our character can be consciously evaluated and developed – this differentiates humans from animals.

⚄ Dąbrowski was deeply concerned with the unique traits and personality of each individual. He asks us to develop and differentiate ourselves and to understand, appreciate, and accept the differences of others.

⚃ 3.5.1.5 Other developmental theories fall short.

⚄ The differentiation of developmental levels is common in theories of biology, philosophy and psychology:

⚅ Many theories present various hierarchies detailing levels.

⚅ A variety of descriptions and explanations of psychological and personality development have been proposed.

⚅ Most approaches suggest all people have the potential to advance, but most people fail to achieve their full potential for various reasons (e.g. run out of energy; social blocks).

⚄ Dąbrowski said he could not find a psychological theory that could explain his observations of both the lowest behaviors and highest achievements of people.

⚄ His goal: to write a “general theory of development” accounting for the wide range of behaviors seen, and explaining the factors and processes that he believed are associated with advanced development.

⚃ 3.5.1.6 Personality theories.

⚃ 3.5.1.7 Several radical core ideas.

⚄ “Dynamics of concepts:” Dąbrowski called for a new way to look at concepts. Psychological attributes often vary widely with development and over levels. Thus, they require flexible and “dynamic” concepts to fully and accurately describe them.

⚅ “Many-sided and authentic development of man implies the formation of an adequate system of concepts and terms which would correspond to the new higher stages of this development” . . . This process of transformation of concepts and terms in their intellectual and experiential aspects can be called ‘the drama of the life and development of concepts’” (1973, pp. xiv-xv).

⚅ “This process of dynamization of concepts will more and more express the close association and interconnection of intellectual and emotional functions. . . . should allow a much more incisive analysis of the understanding of oneself, of other individuals and human groups” (1973, p. xiii).

⚄ Psychoneuroses: Rejecting traditional views, psychoneuroses are seen as a critical part of growth. Severe depression, self-doubt & anxieties are the crises (dis-ease) that challenge one’s secure adjustment to the status quo and force self-examination.

⚅ “The psychoneurotic problem is one of the lack of adjustment manifesting protest against actual reality, and the need for adjustment to hierarchy of higher values: to adjust to that which ‘ought to be’” (1972, p. 3).

⚅ “Psychoneurotics, rather than being treated as ill, should be considered as individuals most prone to a positive and even accelerated psychic development” (1972, p. 4).

⚅ “Nervousness, neuroses, and especially psychoneuroses, bring the nervous system to a state of greater sensitivity. They make a person more susceptible to positive change. The higher psychic structures gradually gain control over the lower ones” (1972, p. 41).

⚄ Positive disintegration: Growth takes place when one’s status quo undergoes dis-integration. This disintegration is positive when it leads to higher development, not simply a retrogressive re-integration.

⚅ “The term disintegration is used to refer to a broad range of processes, from emotional disharmony to the complete fragmentation of the personality structure, all of which are usually regarded as negative” (1964, p. 5).

⚅ “Disintegration is the basis for developmental thrusts upward, the creation of new evolutionary dynamics, and the movement of the personality to a higher level, all of which are manifestations of secondary integration” (1964, p. 6).

⚅ “Crises are periods of increased insight into oneself, creativity, and personality development” (1964, p. 18).

⚅ “Inner conflicts often lead to emotional, philosophical and existential crises” (1972, p. 196).

⚄ Levels: Psychology can best be understood using a levels approach. Intellect (IQ), instinct and emotion can be described on different levels. Appreciating levels gives context & perspective to the wide range of behaviour humans express.

⚅ “Lower levels of functions are characterized by automatism, impulsiveness, stereotypy, egocentrism, lack or low degree of consciousness. … Higher levels of functions show distinct consciousness, inner psychic transformation, autonomousness, creativity” (1972, p. 297).

⚄ Unilevelness: “without a consideration of the multilevelness of life, without ideas. It [life] is a unilevel, statistical, adjusting, sensual life with intelligence in the service of primitive instincts. It is ‘ordinary’ life” (Cienin, 1972, p. 65).

⚅ Unilevel processes “‘everything goes,’ or ‘black and white are equally attractive’” (1996, p. 150).

⚅ “Life begins only with a hierarchy” (Cienin, 1972, p. 65).

⚄ Multilevelness: Describes the hierarchical nature of reality. Growth is connected to perception of higher reality, creating comparisons and conflicts between higher and lower levels.

⚅ “The perception of the external world changes as a function of a new multilevel conception of reality” (1996, p. 106).

⚅ “The recognition of multilevelness of mental functions and structures in oneself allows analogous recognition with regard to other people” (1973, p. 8).

⚅ “Only with the appearance of self-evaluation do we have a multilevel component” (1996, p. 38).

⚅ “Individual perception of many levels of external and internal reality appears at a certain stage of development, here “called multilevel disintegration” (1972, p. 298).

⚅ “The functions of multilevel disintegration are to a considerable extent volitional, conscious, and refashioning functions, in relation to lower levels” (1967, p. 74).

⚄ Developmental potential: Exemplars of development show a unique set of characteristics called development potential (DP). Strong positive DP is a genetically based foundation for advanced psychological development. Not everyone has sufficient positive genetic potential to reach full development.

⚅ “Hyperexcitability,” “psychic overexcitability” and “overexcitability” were described in Dąbrowski’s 1937 English monograph.

⚅ Developmental potential is the “The constitutional endowment which determines the character and the extent of mental growth possible for a given individual” (1972, p. 293).

⚅ “Developmental potential can be assessed on the basis of the following components: psychic overexcitability, special abilities and talents, and autonomous factors (notably the third factor)” (1972, p. 293).

⚅ “The prefix over attached to ‘excitability’ serves to indicate that the reactions of excitation are over and above average in intensity, duration and frequency” (1996, p. 7).

⚅ “Psychic overexcitability is a term introduced to denote a variety of types of nervousness” (Dąbrowski, 1938, 1959).

⚅ “High overexcitability contributes to establishing multilevelness, however in advanced development, both become components in a complex environment of developmental factors” (1996, p. 74).

⚅ “It appears in five forms: emotional, imaginational, intellectual, psychomotor, and sensual” (1996, p. 7).

⚄ Dynamisms: “biological or mental force(s) controlling behavior and its development. Instincts, drives, and intellectual processes combined with emotions are dynamisms” (1972, p. 294).

⚅ “intrapsychic factors which shape development” (1996, p. 5).

⚃ 3.5.1.8 A nomological network of constructs.

⚄ Dąbrowski’s work contains many (~20) interrelated, generally unique constructs, often forming hierarchies.

⚄ For the seminal article on constructs see Cronbach & Meehl, (1955).

⚄ A nomological network is a broadly integrative theoretical framework that identifies the key constructs associated with a phenomenon of interest and describes the relationships among those constructs.

⚃ 3.5.1.9 What is development?

⚄ Dąbrowski presented a “mixed” view of development.

⚄ Traditional views of development are ontogenetic: a predictable, sequential, chronological timeline (milestones). Higher levels unfold from, and are based upon, lower ones.

⚄ Dąbrowski described both ontogenetic pathways as well as non-ontogenetic aspects of development, depending upon the features and levels involved.

⚄ Non-ontogenetic aspects do not arise from, are not based upon, nor are they predictable from, the features of lower levels. They are predicated on “other factors” or emerge anew as evolution proceeds.

⚄ This represents a metaphysical and autopoietic approach.

⚄ Metaphysical aspects: In the self, “the inner psychic milieu” and “third factor” arise from genetic “roots” but transcend their origins to become emergent, independent developmental forces.

⚄ Higher levels are “newer” evolutionary steps, achieved in TPD through positive disintegration. Lower levels break up to be replaced by revised, higher structures.

⚄ “Two main qualitatively different stages and types of life: the heteronomous, which is biologically and socially determined, and the autonomous, which is determined by the multilevel dynamisms of the inner psychic milieu” (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 5).

⚅ Each has characteristic developmental processes.

⚃ 3.5.1.10 An emotion – value based approach.

⚄ Values and moral behavior are critical – when one comes to see what “ought to be” versus “what is.”

⚄ Our emotions are the ultimate guide to our values, sense of self, and behavior, not our intelligence.

⚄ Values are individual but not relative – there are core objective (universal) values that authentic humans will independently discover and embrace as they build their own unique value systems and personalities.

⚄ Dąbrowski saw emotions and values as synonymous.

⚄ Education must prepare the child for life using a balanced approach; personality, intellect and emotion are all important. Goal: to foster a unique, autonomous person, guided by their own emotions and values.

⚃ 3.5.1.11 The role of emotion in development.

⚄ Emotion anchors and guides the creation of autonomous and authentic human values.

⚄ Our feelings work with imagination to develop a sense of what is higher and what ought to be, over “what is.”

⚅ We move away from what feels bad / wrong / lower.

⚅ We move toward what feels good / right / higher.

⚄ If we become conscious of our higher emotions, we can use them as a guide to direct cognition to strive for what “ought to be” – toward “higher possibilities.”

⚅ Intelligence comes to serve and implement our personality ideal: an image of our unique self, based on our feelings of who we ought to strive to be.

⚃ 3.5.1.12 Emotion – A new appreciation.

⚄ The highest levels in traditional theories are based on cognition (e.g. Platonic model, Piagetian model).

⚅ The traditional goal is to have reason control and direct passion (Plato); this approach has predominated Western education and psychology.

⚄ In TPD, emotions are evaluated based on levels of development: the theory differentiates higher vs. lower emotions.

⚅ Dąbrowski used to say: Love at Level I compared to love at level IV is as different as love is from hate.

⚄ Dąbrowski’s observation: In “authentic” development, “higher” emotions guide individual values and define our sense of who we want to be. Intelligence becomes subservient to the guidance of our higher emotions.

⚃ 3.5.1.13 Dąbrowski’s English books.

⚄ The titles of Dąbrowski’s six major English books reflect the major themes of his approach:

⚅ “Positive Disintegration” (1964).

⚅ “Personality Shaping Through Positive Disintegration” (1967).

⚅ “Mental Growth Through Positive Disintegration” (1970).

⚅ “Psychoneurosis is not an Illness” (1972).

⚅ “Dynamics of Concepts” (1973).

⚅ “Multilevelness of Emotional and Instinctive Functions” (1996).

⚂ 3.5.2 Who was Kazimierz Dąbrowski?

⚃ 3.5.2.1 Synopsis: Kazimierz Dąbrowski (1902-1980).

⚄ A Polish psychologist and psychiatrist.

⚄ Deeply affected by his life experience, first as a child eyewitness to the aftermath of horrific battles in WW I.

⚄ Pursued a very comprehensive and diverse education.

⚄ Saw that people display wide variations in how they experience and feel life: some seem to feel more.

⚄ Had strong “overexcitability/nervousness” as a youth.

⚄ Deeply affected again by WW II. Later, under Stalinist authorities, he was imprisoned for 18 months. After his release, his activities were closely controlled.

⚄ Despite his challenges, he published extensively.

⚄ For biographies, see https://www.positivedisintegration.com/

⚃ 3.5.2.2 A precocious student.

⚄ Dąbrowski aspired to be a journalist. In junior high school, he enrolled as a free listener at university, he was later granted 2 years of university study (Skrzyniarz, 2019).

⚄ Dąbrowski did a Masters in philosophy and considered a career in music, but his best friend (a fellow student) committed suicide, changing the direction of his life.

⚄ Dąbrowski entered medicine taking courses from eminent Polish psychiatrist, Jan Mazurkiewicz, a follower of J. H. Jackson. In 1928, he took courses from Édouard Claparède and Jean Piaget, writing a thesis on suicide in 1929.

⚄ He completed a doctorate degree in psychology in 1931, writing another thesis on self-mutilation (1934/1937).

⚃ 3.5.2.3 A diverse education continues.

⚄ Studied psychoanalysis in Vienna under fellow Pole Wilhelm Stekel (and attended lectures by Freud).

⚄ In Paris he practiced psychiatry under Pierre Janet.

⚄ Dąbrowski learned German, Spanish, Russian and French. Centers studying TPD were built in Spain and Lima, Peru (he lectured there). Books were published in Spanish and French. His 1929 thesis was in French.

⚄ In 1933, Dąbrowski spent a year at Harvard and Boston (sponsored by the Rockefeller foundation).

⚅ In the 1930s, he organized mental health services and clinics in Poland (with Rockefeller funding).

⚅ Continued to study and write prolifically.

⚃ 3.5.2.4 A promising career interrupted by the war.

⚄ First mentioned emotional and sensual overexcitability in 1929, added psychomotor and imaginational in a 1935 book on a study of 250 “normal IQ students.”

⚄ During WWII, he was imprisoned several times by the German police (released for ransom) but avoided incarceration in the concentration camp system.

⚄ In the late 1940s, Dąbrowski began to resume his work on mental health and again visited Harvard.

⚄ In 1950, he was imprisoned by the Stalinist authorities for 18 months. Closely monitored after release.

⚄ 1958: first mention of intellectual hyperactivity.

⚄ Introduced ideas of integration and disintegration incrementally, in works in 1937, 1946, and 1949.

⚃ 3.5.2.5 Roots in Canada.

⚄ In 1964 Dąbrowski worked with Jason Aronson in New York, leading to the book Positive Disintegration. Met philosopher Andrew Kawczak in Montréal.

⚄ In 1965, hired by University of Alberta, moved his family to Edmonton (also worked at Université Laval (Laval University), Quebec City).

⚄ In 1966, met Abraham Maslow and the two became friends and correspondents.

⚄ Several of his Edmonton students became co-authors; Dexter Amend, Michael Piechowski & Marlene Rankel.

⚄ For the rest of his life, split his time between Alberta, Québec, and Poland. Worked tirelessly to write about and promote TPD — he never seemed to stop.

⚃ 3.5.2.6 A chapter closes.

⚄ In 1975, at the age of 73, Dąbrowski purchased an estate in Poland with plans to develop a new mental health center.

⚄ In 1976, I became Dąbrowski’s last student in Edmonton and he asked me to keep his theory alive. I later received his unpublished papers.

⚄ In 1979, Dąbrowski had a serious heart attack in Edmonton and died in Warsaw, November 26, 1980.

⚄ He was buried beside his old friend, Piotr Radlo, in the forest near his old Institute at Zagórze, Poland.

⚄ I became a psychologist, created the TPD webpage, archived his work and participated in conferences.

⚄ Piechowski took Dąbrowski’s work to gifted education, emphasizing OE. This created a new audience.

⚂ 3.5.3 Marie Jahoda.

⚃ 3.5.3.1. Marie Jahoda was a major influence on Dąbrowski.

⚄ Jahoda (1958, p. 23) delineated six main features of positive mental health:

⚅ 1. Indicators of positive mental health should be sought in the attitudes of an individual toward his own self. Positive self-attitudes (self-perception).

⚅ 2. The individual’s style and degree of growth, development, or self-actualization are expressions of mental health. This set of criteria, in contrast to the first, is not concerned with self-perception but with what one does with one’s self over a period of time.

⚅ 3. Integration: A central synthesizing psychological function, incorporating some of the suggested criteria defined in 1) and 2) above. Integration is the relatedness of all processes and attributes in an individual.

⚅ 4. Autonomy singles out the individual’s degree of independence from social influences as most revealing of the state of his or her mental health;

⚅ 5. The adequacy of an individual’s perception of reality.

⚅ 6. There were suggestions that environmental mastery be regarded as another criterion for mental health.

⚄ Following Jahoda (1958), Dąbrowski said that mental health should not be defined simply by the presence or absence of symptoms, rather, definitions of mental health must be concerned with views of individuals as they ought to be and by the potential of the individual to achieve ideal, desirable, developmental qualities.

⚄ Dąbrowski defined mental health as: “Development towards higher levels of mental functions, towards the discovery and realization of higher cognitive, moral, social, and aesthetic values and their organization into a hierarchy in accordance with one’s own authentic personality ideal” (1972, p. 298).

⚄ The influence of Jahoda’s six main points can be felt in Dąbrowski’s thinking, especially in terms of the goal of advanced development [paraphrased]:

⚅ An autonomous, consciously derived hierarchy of values, marking the creation of an idealized vision of self – the unique personality of the individual, encapsulated by his or her personality ideal.

⚄ Dąbrowski believed that the moral guidelines one ought to follow must be of one’s own creation. To paraphrase Frederick Nietzsche, each of us must create our own values and personality and thus walk our own path in life.

⚄ Dąbrowski’s observations of people and his adoption of Jahoda led him to an unusual conclusion: that individual personality is not universally, or even commonly, achieved. The average “well socialized” person lacks a unique personality and therefore cannot be considered mentally healthy – the “state of primary integration is a state contrary to mental health” (1964b, p. 121)

⚄ “Mental illness consists in the absence or deficiency of processes which effect development”:

⚅ “1) either a strongly integrated, primitive, psychopathic structure [Level I], or

⚅ 2) a negative, non-developmental disintegration (psychosis)” (1970, p. 173).

⚂ 3.5.4 Multilevel and Multidimensional Approach.

⚃ 3.5.4.1. Levels of function.

⚄ Definition: “The qualitative and quantitative differences which appear in mental functions as a result of developmental changes. …

⚅ Lower levels are characterized by automatism, impulsiveness, stereotypy, egocentrism, lack of, or low degree of consciousness. …

⚅ Higher levels show distinct consciousness, inner psychic transformation, autonomousness, creativity” (1972, p. 297).

⚄ Basic to Dąbrowski’s view of authentic human beings:

⚅ “The reality of mental functions in man is dynamic, developmental and multilevel” (1970, p. 122).

⚄ Dąbrowski stressed levels in TPD are only a heuristic device, not to be taken too literally (Stupak & Dyga, 2018).

⚃ 3.5.4.2 The unilevel versus the multilevel.

⚄ Two fundamentally different views of reality. The lower, basic perception is horizontal – unilevel. The higher, developmental view is vertical – multilevel.

⚄ Unilevel views of reality encompass only horizontal elements. Only phenomena on the same level are perceived and considered in decision making.

⚄ Most behaviors can be seen as either UL or ML.

⚄ Likewise, motivations of behavior and processes of development can reflect either UL or ML character.

⚄ Multilevelness is paramount because it allows us to see and compare the higher versus lower. Over time, ideally, the higher aspect will increasingly be chosen.

⚃ 3.5.4.3 Unilevelness (UL) and multilevelness (ML).

⚄ The “average” view of life is horizontal – unilevel:

⚄ (Ken Wilber: “flatlanders,” Bertalanffy and Yablonsky: “robopaths”)

⚅ “Robots” blindly follow social roles and values.

⚅ “Animal model” – stimulus-response reactions.

⚅ Equal alternatives create false “illusion of choice.”

⚅ Conflicts between different but equivalent choices.

⚅ No vertical component to allow for higher growth.

⚄ Development is linked to a “new” – vertical – ML view:

⚅ One begins to see higher possibilities in comparison to lower realities and alternatives.

⚅ A vertical, ML view creates a hierarchical model of life, of values and of behavior – allows us to see and choose the higher over the lower.

⚃ 3.5.4.4 Multilevelness – overview.

⚄ Levels are a philosophical foundation of the theory.

⚄ Level based analysis has a long philosophical history.

⚄ Premise: Reality and our perception of reality can be differentiated into a hierarchy of levels.

⚄ The reality that one perceives reflects one’s given level of development – wide differences are observed.

⚄ Most psychological features change quantitatively. Higher levels show qualitative changes as they develop or emerge.

⚄ This allows us to differentiate higher, more developed levels from lower, earlier, less developed levels.

⚄ Differentiation of lower and higher levels is basic to Dąbrowski’s view of mental health and development.

⚃ 3.5.4.5 Multilevelness.

⚄ Definition: “Division of functions into different levels: for instance, the spinal, subcortical, and cortical levels in the nervous system. Individual perception of many levels of external and internal reality appears at a certain stage of development, here called multilevel disintegration” (1972, p. 298).

⚄ The dynamic process of “hierarchization” expands our range of human experience, creating a new, critical type of conflict: vertical conflicts between higher and lower alternatives and choices.

⚄ “It appears obvious that the ability to understand and to successfully apply the concept of multilevelness depends upon the development of personality of the individual” (1973, p. x).

⚃ 3.5.4.6 Multilevelness as a growth process.

⚄ One begins to imagine the higher possibilities in life.

⚅ Creates a new goal: a unique personality ideal based on the “discovery” of our deep essence.

⚄ Once the higher alternative is seen, acting on the lower creates guilt, unhappiness, feelings of inferiority:

⚅ Vertical conflicts / dissonance become a vital, internal driving force of personality change.

⚅ I think I want the lower, but on reflection, I know I must choose the higher – because I feel it is right.

⚄ In development, “hierarchization” becomes a key process of ML.

⚅ Contrasts of the lower and higher create hierarchies.

⚄ The true solution to human problems must involve ascent; moving one not only forward but upward.

⚃ 3.5.4.7 Multidimensionality.

⚄ Dąbrowski integrated a multidimensional analysis into multilevelness.

⚄ “The transition toward ‘higher levels of values’ does not consist in the loosening of intellectual and semantical functions, but is an expression of a multilevel and multidimensional ‘developmental drama’” (1973, p. 143).

⚄ “It seems that the multidimensional attitude in every field of life, including creative work, induces and forces man to overstep the scope of his limited field of knowledge and to explore what is not only outside it, but also above it. When one adopts the multidimensional attitude one begins as a rule to understand and experience religious life and all that goes with it” (1967, pp. 25-26).

⚄ “The sense of humility reflects one’s multidimensional world outlook, in which a man realizes the existence of higher values and at the same time soberly appraises his own level and possibilities of development” (1967, p. 29).

⚄ “The concept of mental health must be based on a multi-dimensional view of personality development. Higher levels of personality are gradually reached both through adaptation to exemplary values and through disadaptation to lower levels of the external and internal environments” (1964, pp. 124-125).

⚄ “It should proceed from basic premises to knowledge wider in scope, to a point at which we pass from an unidimensional ‘I know’ to a multidimensional ‘I understand.’ Knowledge is usually unidimensional and understanding multidimensional; knowledge is based on perception and judgment, understanding involves also experience and intuition which add depth to the perception and judgment” (1967, pp. 11-12).

⚃ 3.5.4.8 Multilevelness and multidimensionality lead to multiple meanings.

⚄ Examining one dimension across various levels often leads to the observation that each dimension — each psychological feature — has a different expression on each level: A given dimension has different meanings, different expressions and different impacts on each level.

⚄ The combination of multiple levels and dimensions creates a comprehensive but complicated analysis that is difficult to operationalize or measure.

⚄ A full description of reality requires a multidimensional and multilevel perception of reality, both of the external environment and of one’s inner psychic milieu, including feeling, thoughts, imagination, instincts, empathy, and intuition.

⚃ 3.5.4.9 Developmental complexity.

⚄ The level of development is not uniform across all dimensions within a person. People are often on different levels on different dimensions:

⚅ A person may be at a high level cognitively and on a low level emotionally (and morally); this is common and seems to be the social status quo.

⚄ Dąbrowski called this one-sided development.

⚄ One-sided development: “Type of development limited to one talent or ability, or to a narrow range of abilities and mental functions” (1972, p. 300).

⚅ “Grave affective retardation is usually associated with above average intelligence subordinated to primitive drives” (1970, p. 30).

⚄ To overcome one-sided development, Dąbrowski advocated we strive to achieve balance by focusing more attention on the child’s weaker talents. If a child is a mathematical prodigy, weak in English, then focus on the overall development of the child and on English.

⚄ A study of child prodigies found that most parents exclude everything except the single talent, leading to various psychological issues later in life (Hulbert, 2018).

⚃ 3.5.4.10 Multilevel and multidimensional analysis.

⚄ Behavior involves an ongoing (dynamic) interaction of dimensions and levels: A behavior is expressed differently on different levels (this is obvious if comparing UL to ML).

⚄ MD and ML must be used together to examine, evaluate, and understand behavior in the context of the developmental level and motivation that spawned it.

⚄ According to Dąbrowski, determining motivation behind behaviour often requires observation over time. In many cases, motivation holds greater significance than behaviour itself.

⚄ Ken Wilber used a similar approach called “the all [four] quadrant approach.”

⚄ “An adequate grasp of the essential constituents of human existence is possible only from the standpoint and through intense and accelerated mental development. This development must be multidimensional and multilevel. It is multidimensional and fully rounded, if it is not restricted to the perfection of one or some capacities and skills, but includes a transformation and refinement of all basic aspects of mental life, especially innate drive, emotions, intellect, volition, imagination, moral social, aesthetic, religious sensitivity, etc. It is multilevel if mental transformations consist not only in quantitative growth and replacement of some elements with others, but if such new insights and new qualities are acquired which make man capable of overcoming his hereditary and social determination and to progress toward a self-controlled, creative, empathetic and authentic form of life” (1970, p. 15).

⚄ Combining multilevelness and multidimensionality complicates the assessment of levels and may make assessment unfeasible when many dimensions are included.

⚅ Current educational testing focuses on only one or two dimensions (almost always cognitively based).

⚅ Dąbrowski emphasized that we need a richer, broader approach to measure human development and potentials.

⚄ People are often at different levels of development on different dimensions, e.g., intellect vs. emotion. We need to consider the level for each dimension we choose to look at.

⚃ 3.5.4.11 Examples of dimensions:

⚄ What dimensions should we include in our analysis?

⚂ 3.5.5 Dąbrowski’s 5 Levels.

⚃ 3.5.5.1. Level I

⚄ Dąbrowski believed that the majority (about 65%) of people live life at Level I – Primary Integration:

⚅ A stable, rigid, integrated, horizontally based level.

⚅ Behavior is automatic, reflexive, rote, unthinking.

⚅ Instinct (first factor) and social forces (second factor) influence and determine most behavior.

⚅ A difficult level to break free of because integration creates a strong sense of belonging and security (“security of the herd”).

⚅ Inner harmony: most conflicts are external, inner sense of “always being right,” of selfish entitlement, “don’t worry about the other guy’s problems.”

⚄ Integration: “Consists in an organization of instinctive, emotional and intellectual functions into a coordinated structure” (1972, p. 296).

⚄ “Primitive Integration” (primary integration, Level I):

⚅ “An integration of all mental functions into a cohesive structure controlled by primitive drives” (1972, p. 302).

⚅ “Individuals with some degree of primitive integration comprise the majority of society” (1964, p. 4).

⚅ “Among normal primitively integrated people, different degrees of cohesion of psychic structure can be distinguished” (1964, p. 66).

⚅ “Psychopathy represents a primitive structure of impulses, integrated at a low level” (1964, p. 73).

⚄ An illustrative hierarchy of Level I: (from E. Mika)

⚅ Average person exhibiting psychoneuroses: highest sub-level of Level I

⚅ Average person showing social conformity [“1b”] (dominant type in the population)

⚅ Psychopath but maintains social conformity for self-gain (CEO who “bends the law,” takes advantage wherever possible) Asocial [“snakes in suits”]

⚅ Psychopath exhibiting antisocial behavior: lowest sub-level of Level I [“1a”]

⚄ The more rigid one’s initial integration, the harder it is to disintegrate, change, and to grow.

⚃ 3.5.5.2 Dąbrowski’s Levels – II, III and IV.

⚄ 3 levels describe varying degrees of disintegration:

⚅ Level II – Unilevel Disintegration: Horizontal conflicts create ambiguity and ambivalence. Very stressful, chaotic period, maximum dis – ease:

⚄ High risk of falling back or falling apart.

⚄ Dąbrowski described this as a transitional level.

⚄ Paradigm shift: multilevel, vertical aspects appear.

⚅ Level III – Spontaneous: Multilevel, vertical conflicts arise spontaneously, create disintegration.

⚅ Level IV – Organized (Directed): We now see and actively seek out vertical conflicts, we play a volitional role in “directing” crises and our own development.

⚃ 3.5.5.3 Paradigm shift from UL to ML.

⚄ Initially, ML awareness creates great internal stress because choosing the lower has become habitual. Now, “the possibility” of a different and better choice comes into view. This contrast is upsetting and, at first, is quite spontaneous. “Vertical conflicts” arise.

⚄ The transition to multilevelness is the “greatest step” in growth and also the most perilous: As one’s old, status quo unilevel frame of reference crumbles, feelings of chaos, anxiety and dread are common. Dąbrowski said that the shift from the unilevel to the multilevel / vertical perception of life is the key to development.

⚄ One’s once secure and familiar foundation is lost without seeing a “new” pathway to one’s future.

⚅ “The dark night of the soul” is a common experience, reflects an existential crisis – one’s world is in chaos.

⚅ The shift takes energy and places major demands on the person: one may initially feel self-alienated and be overwhelmed with depression and despair.

⚄ Initially one often experiences strong urges to return to the security of unilevelness.

⚄ Once one truly sees and appreciates the vertical, there is no turning back to a unilevel existence.

⚅ Dąbrowski compared this with Plato’s cave: once one breaks free and “sees the [sun]light,” one can no longer be happy returning to live in the darkness.

⚃ 3.5.5.4 Secondary integration.

⚄ Secondary Integration (Level V): “the integration of all mental functions into a harmonious structure controlled by higher emotions such as the dynamism of personality ideal, autonomy and authenticity” (1972, p. 304).

⚄ “The embryonic organization of secondary integration manifests itself during the entire process of disintegration and takes part in it, preparing the way for the formation of higher structures integrated at a higher level” (1964, pp. 20-21).

⚄ Secondary integration is not the endpoint of mental development – it continues throughout life via the personality ideal and the instinct for self-perfection.

⚄ Full realization of multilevelness and personality ideal.

⚄ One’s unique hierarchy of values directs behavior.

⚄ Personality ideal and third factor direct autonomous, volitional, unique personality – “a good person” – this is what is right – for you.

⚄ Exemplars describe and show us this highest level.

⚄ Inner harmony: we are satisfied that our values and behavior now reflect our “true” self as we feel it ought to be – no internal conflict.

⚄ May have more external conflicts – strong sense of social justice motivates social action and reform.

⚄ Rarely seen (but the future trend in evolution?).

⚂ 3.5.6 Disintegration.

⚃ 3.5.6.1. Disintegration.

⚄ Disintegration: “Loosening, disorganization, or dissolution of mental structures and functions” (1972, p. 293).

⚄ “The term disintegration is used to refer to a broad range of processes, from emotional disharmony to the complete fragmentation of the personality structure, all of which are usually regarded as negative” (1964, p. 5).

⚄ Dąbrowski described various types of disintegration:

⚅ Unilevel / Multilevel.

⚅ Negative / Positive.

⚅ Spontaneous (Unpredictable) / Organized (Directed).

⚅ Partial / Global.

⚃ 3.5.6.2 Role of crises in life.

⚄ “Every authentic creative process consists of ‘loosening,’ ‘splitting’ or ‘smashing’ the former reality. Every mental conflict is associated with disruption and pain; every step forward in the direction of authentic existence is combined with shocks, sorrows, suffering and distress” (1973, p. 14).

⚄ “The chances of developmental crises and their positive or negative outcomes depend on the character of the developmental potential, on the character of social influence, and on the activity (if present) of the third factor. . . . One also has to keep in mind that a developmental solution to a crisis means not a reintegration but an integration at a higher level of functioning” (1972, p. 245).

⚄ “Crises are periods of increased insight into oneself, creativity, and personality development” (1964, p. 18).

⚄ “Crises, in our view, are brought about through thousands of different internal and external conflicts, resulting from collisions of the developing personality with negative elements of the inner and external milieus” (1972, p. 245).

⚄ “Experiences of shock, stress and trauma, may accelerate development in individuals with innate potential for positive development” (1970, p. 20).

⚄ “Inner conflicts often lead to emotional, philosophical and existential crises” (1972, p. 196).

⚄ “We are human inasmuch as we experience disharmony and dissatisfaction, inherent in the process of disintegration” (1970, p. 122).

⚄ “Prolonged states of unilevel disintegration (Level II) end either in a reintegration at the former primitive level or in suicidal tendencies, or in a psychosis” (1970, p. 135).

⚄ Inner conflict is a cause of positive disintegration and subsequent development – conflict acts as a motive to redefine, refine, and discover one’s “new” values.

⚄ Inner conflict is also the result of the process of positive disintegration and the operation of the dynamisms of development.

⚃ 3.5.6.3 Internal conflict.

⚄ Dąbrowski believed that dis-ease is necessary as a motivation to change the status quo. The amount of inner conflict is linked to the degree of change – maximum at Level II and in the borderline region between Level II and III:

⚄ Definition of positive: “By positive we imply here changes that lead from a lower to a higher (i.e. broader, more controlled and more conscious) level of mental functioning” (1972, p. 1).

⚄ Definition of Positive Disintegration: “Positive or developmental disintegration effects a weakening and dissolution of lower level structures and functions, gradual generation and growth of higher levels of mental functions and culminates in personality integration” (1970, p. 165).

⚄ “The term positive disintegration will be applied in general to the process of transition from lower to higher, broader and richer levels of mental functions. This transition requires a restructuring of mental functions” (1970, p. 18).

⚄ “Loosening, disorganization or dissolution of mental structures and functions” (1970, p. 164).

⚄ “Positive when it enriches life, enlarges the horizon, and brings forth creativity, it is negative when it either has no developmental effects or causes involution” (1964, p. 10).

⚄ Recovery from a crisis can lead to a reintegration at the former level and equilibrium or to a more healthy integration and new equilibrium on a higher level.

⚄ If a person has strong developmental potential, even severe crises can be positive and lead to growth.

⚄ “The close correlation between personality development and the process of positive disintegration is clear” (1964, p. 18).

⚄ “In education, the theory emphasizes the importance of developmental crises and of symptoms of positive disintegration. It provides a new view of conduct difficulties, school phobias, dyslexia, and nervousness in children” (1964, p. 23).

⚃ 3.5.6.4 Summary of disintegration.

⚄ Creates the possibility/opportunity of higher growth.

⚄ Strong OE gives everyday experience an intense and unsettling quality: one is “jolted” into seeing “more.”

⚄ One becomes aware of a continuum of higher versus lower aspects of both inner and outer reality.

⚄ Developing multilevelness creates ‘vertical’ conflicts and a new, vertical, upward sense of direction.

⚄ Developmental instincts and one’s emotions naturally and intuitively draw one toward higher choices.

⚄ Our lower instinctual and socially based values and habits are brought under conscious scrutiny and disintegrate to be replaced by self-chosen values.

⚄ A “hierarchization” of life develops: guided by emotion and one’s ability to imagine higher possibilities, a vertical perception and categorization helps create an autonomous, consciously chosen hierarchy of values.

⚄ These inner values form the basis of a person’s own unique personality ideal: his or her own sense of who he or she ought to be.

⚄ One’s behavior slowly comes to reflect these higher, internal values.

⚄ At higher levels of development, individuals form unique hierarchies of values. Some of these values converge among people and reflect universal values.

⚂ 3.5.7 Developmental Potential.

⚃ 3.5.7.1. Advanced development is rare.

⚄ In TPD, people dominated by their lower instincts seem to have little potential to develop or to change.

⚄ People dominated by socialization may possess potential to develop but social forces and peer pressure are strong and vigorously resist change.

⚄ Some people appear to have strong autonomous potential to develop (can’t be held back). Often go on to become exemplars of advanced development.

⚄ Dąbrowski studied exemplars of personality development and described common traits he saw in them that he called Developmental Potential (DP).

⚄ Growth “occur[s] only if the developmental forces are sufficiently strong and not impeded by unfavorable external circumstances. This is, however, rarely the case. The number of people who complete the full course of development and attain the level of secondary integration is limited. A vast majority of people either do not break down their primitive integration at all, or after a relatively short period of disintegration, usually experienced at the time of adolescence and early youth, end in a reintegration at the former level or in partial integration of some of the functions at slightly higher levels, without a transformation of the whole mental structure” (1970, p. 4).

⚄ “A fairly high degree of primary integration is present in the average person; a very high degree of primary integration is present in the psychopath. The more cohesive the structure of primary integration, the less the possibility of development; the greater the strength of autonomic functioning, stereotypy, and habitual activity, the lower the level of mental health” (1964 p.121).

⚅ Note: Dąbrowski’s usage of the term “psychopath” reflects the European connotation of the term: an individual with strong “constitutional factors” that act to inhibit potential development (in contrast with the sociopath; one having social factors that block development). Still, his usage reflects contemporary views of psychopathy and highlights its adevelopmental nature.

⚄ Ideal maturation is prolonged:

⚅ [People with strong developmental “endowment”] “must have much more time for a deep, creative development and that is why you will be growing for a long time. This is a very common phenomenon among creative people. Simply, they have such a great developmental potential, ‘they have the stuff to develop’ and that is why it takes them longer to give it full expression” (1972, p. 272).

⚄ Exemplars are role models of higher levels:

⚅ Dąbrowski was optimistic that exemplars of the highest levels are role models who represent the next steps in Human psychological evolution.

⚃ 3.5.7.2 Where are we today?

⚄ In all existing psychological models, including TPD, advanced development is rarely seen.

⚄ The population distribution of developmental potential.

⚃ 3.5.7.3 The developmental process.

⚄ “The developmental process in which occur ‘collisions’ with the environment and with oneself begins as a consequence of the interplay of three factors: developmental potential, … an influence of the social milieu, and autonomous (self-determining) factors” (1972, p. 77).

⚅ “By higher level of psychic development we mean a behavior which is more complex, more conscious and having greater freedom of choice, hence greater opportunity for self-determination” (1972, p. 70).

⚅ “The individual with a rich developmental potential rebels against the common determining factors in his external environment” (1970, p. 32).

⚃ 3.5.7.4 Traditional developmental features.

⚄ In traditional approaches, cognition is the key component of higher levels:

⚅ Cognition and reason overcome or control emotion.

⚄ TPD reframes and revises traditional roles of mental excitement, emotion and pathology in development.

⚄ Excess excitability, strong emotion, and “pathology” traditionally are seen negatively in mental health.

⚅ “Excess” excitability has been medicated and is often linked to various pathologies, learning disabilities and delinquency.

⚅ “Excess” emotion has often been equated with hysteria.

⚅ “Pathology” traditionally indicates a weakness or defect needing to be treated, ameliorated, palliated, and removed.

⚃ 3.5.7.5 Developmental potential is genetic.

⚄ Definition: “The constitutional endowment which determines the character and the extent of mental growth possible for a given individual” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 293).

⚄ DP can be positive, promoting development; negative and inhibiting development; or equivocal.

⚄ “The relations and interactions between the different components of the developmental potential give shape to individual development and control the appearance of psychoneuroses on different levels of development” (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 78).

⚄ Just as IQ varies in the population, so does DP.

⚄ Most have too little DP to allow for advanced growth.

⚄ A few have strong DP and achieve the highest levels.

⚃ 3.5.7.6 Developmental potential (DP): Overview.

⚄ Several complex and interrelated components of DP:

⚅ The three factors of development.

⚅ Dynamisms.

⚅ Psychoneuroses and positive disintegration.

⚅ Emerging, internal features of the self [Hierarchy of aims, Hierarchy of values, Inner Psychic Milieu, Third Factor, Personality Ideal, etc.].

⚅ The developmental instinct, the creative instinct, and the instinct for self-perfection.

⚅ Overexcitability (Five types).

⚅ Special talents and abilities.

⚃ 3.5.7.7 Key features of DP.

⚄ DP influences how one perceives the environment and determines one’s unique developmental course.

⚄ DP, especially OE, works hand-in-hand with psychoneuroses and positive disintegration to change one’s perception of reality, predisposing development.

⚄ Development is defined by movement towards self-determination and autonomy – toward the third factor, toward self-perfection, and the personality ideal.

⚄ Adjustment to “what is” is generally adevelopmental. Initially, maladjustment results from conflicts with the social environment. A shift to “what ought to be,” leads to a new type of positive adjustment and harmony.

⚄ Developmental potential may be:

⚅ positive or negative / general or specific / strong or weak / expressed or not expressed.

⚄ The most misunderstood aspect of DP is OE:

⚅ OE is usually not appreciated by others or by society.

⚅ OE is often suppressed or hidden by the individual.

⚅ OE needs to be understood in the context of DP and TPD.

⚅ OE may be hard to manage and may be overwhelming.

⚅ OE heightens the joys but also intensifies the lows of life.

⚅ OE needs to be validated – not seen as an abnormality.

⚄ Many aspects of DP have received negligible attention.

⚄ One must “transform” 1st and 2nd factors to develop.

⚄ One with “a rich DP rebels” against “his external environment” and “the laws of biology” (1970, pp. 32-33).

⚄ “Environmental influences collide with those potentials, strengthen or weaken them, but their outcome always depends on an individual’s hereditary endowment:”

⚅ “(1) If the developmental potential is distinctly positive or negative, the influence of the environment is less important. (2) If the developmental potential does not exhibit any distinct quality, the influence of the environment is important and it may go in either direction. (3) If the developmental potential is weak or difficult to specify, the influence of the environment may prove decisive, positively or negatively” (1970, p. 34).

⚄ “In the vast majority of cases, the phenomena of disintegration point to a very great developmental potential” (1970, p. 39).

⚃ 3.5.7.8 Developmental potential: Assessment.

⚄ To assess DP, Dąbrowski described 3 main aspects:

⚅ 1. Special talents and abilities (e.g. IQ, athletic ability, musical or artistic ability).

⚅ 2. Overexcitability (OE).

⚅ 3. “Third Factor” (a strong internal drive to express one’s unique self – factor of autonomous choice).

⚄ “The developmental potential can be assessed on the basis of the following components: psychic overexcitability special abilities and talents, and autonomous factors (notably the Third factor)” (1972, p. 293).

⚃ 3.5.7.9 Overexcitability.

⚄ Clouston (1899) used the term overexcitability in the title of his article: “Stages of over-excitability, hypersensitiveness, and mental explosiveness in children and their treatment by the bromides.”

⚄ Clouston (1899) described overexcitabilities: “They are, in fact, one of the many dangers that beset the earlier stages of that marvellous march of the brain from its inchoate state of childhood up to its all-dominant place in the fully developed organism of the man and woman. They are essentially developmental in character and relationships. The higher brain must rule function and organ and life while it is in the process of development, as well as after its powers are fully formed and its structures completed. In the earlier stages of its growth one part and function of it may run ahead of other parts and functions. (p. 482)

⚄ “The first of those morbid states to which I would direct attention is a simple hyper-excitability; an undue brain reactiveness to mental and emotional stimuli. This may come on at any age, from three years to puberty. The child becomes ceaselessly active, but ever changing in its activity. It is restless and so absolutely under the domination of the idea which has raised the excitement that the power of attending to anything else is for the time being gone. (p. 483)

⚄ Clouston (1899) described imaginational overexcitability, saying: “Another state which is certainly of the nature of disease is that where children become for a time so over-imaginative that they cannot distinguish between their objective experiences and their subjective images, and where, without stimuli from without, mental or bodily, they conjure up fancies so vivid that they mistake them for realities and talk about them accordingly.” … “the intensity and actuality of their imaginations are greater than is consistent with sound working brain” and, at times, these children become “slaves of their over-excited imagination” (p. 484).

⚄ The idea of overexcitabilities and their importance also appear in William James: “Wherever a process of life communicates an eagerness to him who lives it, there the life becomes genuinely significant. Sometimes the eagerness is more knit up with the motor activities, sometimes with the perceptions, sometimes with the imagination, sometimes with reflective thought. But, wherever it is found, there is the zest, the tingle, the excitement of reality; and there is ‘importance’ in the only real and positive sense in which importance ever anywhere can be” (James, 1899, pp. 9-10).

⚄ Dąbrowski’s definition: “Higher than average responsiveness to stimuli, manifested either by psychomotor, sensual, emotional (affective), imaginational, or intellectual excitability or the combination thereof” (1972, p. 303).

⚄ A physiological property of the nervous system: “Each form of overexcitability points to a higher than average sensitivity of its receptors” (1972, p. 7).

⚄ “Psychic hyperexcitability is one of the major developmental potentials, but it also forms a symptom, or a group of general psychoneurotic symptoms” (1970, p. 40).

⚄ Intense overexcitability, especially emotional, may magnify life’s traumas and suicide is a major concern.

⚄ “The prefix over attached to ‘excitability’ serves to indicate that the reactions of excitation are over and above average in intensity, duration and frequency” (1996, p. 7).

⚄ OE affects how a person sees reality: “One who manifests several forms of overexcitability, sees reality in a different, stronger and more multisided manner” (1972, p. 7).

⚄ “Enhanced excitability, especially in its higher forms, allows for a broader, richer, multilevel, and multidimensional perception of reality. The reality of the external and of the inner world is conceived in all its multiple aspects” (1996, p. 74).

⚄ Dąbrowski called OE “a tragic gift”:

⚅ As both the highs and lows of life are intensified.

⚅ Because the world is not yet ready for people who feel at such deep levels.

⚄ “Because the sensitivity [excitability] is related to all essential groups of receptors of stimuli of the internal and external worlds it widens and enhances the field of consciousness” (1972, p. 66).

⚄ “Individuals with enhanced emotional, imaginational and intellectual excitability channel it into forms most appropriate for them” (1972, p. 66).

⚄ The “big 3”:

⚅ “Emotional (affective), imaginational and intellectual overexcitability are the richer forms. If they appear together they give rich possibilities of development and creativity” (1972, p. 7).

⚅ “The overexcitabilities of greatest developmental significance are the emotional, imaginational and intellectual. They give rise to psychic richness, the ability for a broad and expanding insight into many levels and dimensions of reality, for prospection and introspection, for control and self-control (arising from the interplay of excitation and inhibition). Thus they are essential to the development of the inner psychic milieu” (1996, p. 73).

⚅ “A person manifesting an enhanced psychic excitability in general, and an enhanced emotional, intellectual and imaginational excitability in particular, is endowed with a greater power of penetration into both the external and the inner world” (1972, p. 65).

⚅ “. . . These couplings determine a closely woven activity of different forms of enhanced excitability, especially emotional, imaginational and intellectual; they also determine how to make use of the positive aspects of sensual and psychomotor overexcitability by subordinating them to the other three higher forms of overexcitability” (1972, p. 66).

⚄ Dąbrowski linked overexcitability with disintegration:

⚅ [First] “Hyperexcitability also provokes inner conflicts as well as the means by which these conflicts can be overcome” (1970, p. 38).

⚅ Second, hyperexcitability precipitates psychoneurotic processes.

⚅ Third, conflicts and psychoneurotic processes become the dominant factors in accelerated development.

⚄ “It is mainly mental hyperexcitability through which the search for something new, something different, more complex and more authentic can be accomplished” (1973, p. 15).

⚄ Overexcitability helps to differentiate higher from lower experiences and facilitates a multilevel view: “The reality of the external and of the inner world is conceived in all its multiple aspects. High overexcitability contributes to establishing multilevelness” (1996, p. 74).

⚄ Individuals will usually display a characteristic response type – one of the five forms will be dominant, and one will direct one’s OE accordingly: “For instance, a person with prevailing emotional overexcitability will always consider the emotional tone and emotional implications of intellectual questions” (1996, p. 7).

⚄ “Individuals with enhanced emotional, imaginational and intellectual excitability channel it into forms most appropriate for them” (1972, p. 66).

⚄ “Nervous children, who have increased psychomotor, emotional, imaginative, and sensual or mental psychic excitability and who show strength and perseveration of reactions incommensurate to their stimuli, reveal patterns of disintegration” (1964, p. 98).

⚄ “Excessive excitability is, among others, a sign that one’s adaptability to the environment is disturbed. These disintegration processes are based on various forms of increased psychic excitability, namely on psychomotor, imaginative, affectional, sensual, and mental hyperexcitability.” (1967, p. 61).

⚃ 3.5.7.10 Neuroscience support for overexcitability.

⚄ It is beyond the scope of this introduction to fully explore this complex topic (see Tillier 2018).

⚄ In the individual neuron, there are both intrinsic levels of excitability and an ongoing modulation of excitability. These levels are controlled by both genetics – different individuals have slightly different genetics – and, as well, by epigenetics – one’s life experience will modify both the architecture and functional expression of one’s neurons and subsequently adjust neuronal excitability (Armstrong, 2014).

⚄ As neurons operate in microcircuits and as part of larger networks, neuronal control of the balance of excitability and inhibition is a critical factor.

⚄ Many systems require strict homeostatic control (e.g. blood pressure, temperature and respiration). Other systems must be plastic and respond to rapid change (e.g. to remember and learn).

⚄ Genes that control voltage-gated ion channels and calcium transport are consistently found in psychiatric GWAS (Ament et al., 2015). These genes control cellular electrical excitability and calcium homeostasis in neurons (Smoller, 2013). “Alteration in the ability of a single neuron to integrate the inputs and scale its excitability may constitute a fundamental mechanistic contributor to mental disease, alongside with the previously proposed deficits in synaptic communication and network behaviour” (Mäki-Marttunen et al. 2016, p. 1).

⚄ The proof of concept for the neurophysiological mechanisms and genetic (and epigenetic) control of neuronal excitability have been established (e.g., Gulledge & Bravo, 2016; Mäki-Marttunen et al., 2016; Meadows et al., 2016; Rannals et al., 2016; Remme & Wadman, 2012).

⚄ Experience alters the architecture and functional expression of individual neurons and dynamically modifies levels of brain/network variability, flexibility and connectivity (Zhang et al., 2016). . . . These changes impact neuronal excitability (e.g., Chen et al., 2016; Meadows et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016).

⚄ Summary: Contemporary research generally supports Dąbrowski’s approach to overexcitabilities and presents several plausible explanations to account for a hypothesized continuum of levels of excitability occurring between individuals: excitability varies in the population, with “average” excitability as the norm and “overexcitable” individuals as the exception. The control of excitability largely occurs within the individual neuron – each neuron monitors its own firing and can modify its rate of firing, so as to maintain overall network stability. Neurons show intrinsic levels of excitability and ongoing modulation of excitability based upon both genetics and epigenetics.

⚄ For key sources see master references: https://www.positivedisintegration.com/masterref.pdf

⚃ 3.5.7.11. Three factors of development.

⚄ According to Dąbrowski, genetic features are the foundation of both the lower instincts and of the higher features of developmental potential, including the basis of several emergent aspects that eventually eclipse their genetic roots. Dąbrowski described these features as 3 “factors” that influence behavior and development.

⚄ First Factor: “hereditary, innate constitutional elements.” The expression of basic genetic instincts.

⚅ Most basic: primal biological survival instincts.

⚄ Primitive, reflexive instincts and reactions.

⚄ Also contain the roots of developmental potential.

⚄ Today, we see this expressed in our “dog-eat-dog” mentality and social obsession on material success.

⚄ Reflected in egocentrism: Focus on self-satisfaction, feeling good, regardless of costs to others.

⚄ “May be more general or more specific, more positive or more negative” (1970, p. 33).

⚃ 3.5.7.12 First Factor contains both lower and higher elements.

⚄ “General excitability, nuclei of the inner psychic milieu, general interests and aptitudes are examples of general and positive potentials. Specific forms of hyperexcitability such as emotional, imaginational or sensual hyperexcitability, as well as specific interests or aptitudes, such as musical, choreographic or mathematical aptitudes, constitute specific and positive potentials” (1970, pp. 33-34).

⚄ Second Factor: “the influences of the external environment, mainly family and social milieu”(1970, p. 72).

⚅ Most people incorporate and follow social values, rules and roles; learned through parenting and education.

⚅ Moral authority and criteria for good behavior are derived from external (social) values (heteronomy).

⚅ Most people live life under the day-to-day influence of second factor, for example: Kohlberg’s conventional level of moral reasoning.

⚅ Dąbrowski rejected unreflective conformity and saw people who function primarily under social influence as “mentally unhealthy.”

⚄ Most people become socialized and conform without thinking deeply about life – without comparing how things are versus how things could be or ought to be.

⚄ Developmental potential and the environment:

⚅ “If the developmental potential is distinctly positive or negative, the influence of the environment is less important. If the developmental potential does not exhibit any distinct quality, the influence of the environment is important and it may go in either direction. If the developmental potential is weak or difficult to specify, the influence of the environment may prove decisive, positively or negatively” (1970, p. 34).

⚄ Dąbrowski discussed Plato’s allegory of the cave as an illustration.

⚅ We live in a cave, facing a blank wall. Shadows are projected on the wall by unseen puppeteers (education and politics). We sit passively, mistakenly accepting these shadows as reality: second factor. If a person can break free and reach the exit leading out of the cave and up, into the sun, he or she can wake up and start to think independently: third factor. For Plato, this person can become a philosopher and discover real knowledge [Truth].

⚄ The third factor arises from genetic roots but later “emerges” and becomes an autonomous dynamism:

⚅ Third factor becomes an emergent force, eventually expressing our sense of who we ought to be and controlling the direction of our development – it transcends its genetic roots.

⚅ As third factor develops, it compels us to make choices that express our authentic self: to choose what is “more me” and to reject what is “less me.”

⚅ More than just “will” or “will power” – the third factor is the totality of our unique autonomous features and forces.

⚅ Third Factor: “the autonomous factor of development.”

⚅ “The dynamism of conscious choice (valuation) by which one affirms or rejects certain qualities in oneself and in one’s environment” (1972, p. 306).

⚅ “A dynamism of conscious choice by which one sets apart both in oneself and in one’s environment those elements which are positive, and therefore considered higher, from those which are negative, and therefore considered lower. By this process a person denies and rejects inferior demands of the internal as well as of the external milieu, and accepts, affirms and selects positive elements in either milieu” (1996, pp. 38-39).

⚃ 3.5.7.13 The third factor.

⚄ “The third factor is independent from and selective with regard to heredity (the first factor), and environment (the second factor). Its selective role consists in accepting and fostering or rejecting and restraining qualities, interests and desires, which one finds either in one’s hereditary endowment or in one’s social environment. Thus the third factor being a dynamism of conscious choice is a dynamism of valuation. The third factor has a fundamental role in education-of-oneself, and in autopsychotherapy. Its presence and operation is essential in the development toward autonomy and authenticity. It arises and grows as a resultant of both positive hereditary endowment (especially the ability for inner psychic transformation) and positive environmental influences” (1970, pp. 178-179).

⚄ “The principal periods during which the third agent appears distinctly are the ages of puberty and maturation” (1964, p. 56).

⚄ “During the period of puberty, young people become aware of the sense of life and discover a need to develop personal goals and to find the tools for realizing them. The emergence of these problems and the philosophizing on them, with the participation of an intense emotional component, are characteristic features of a strong instinct of development and of the individual’s rise to a higher evolutionary level” (1964, p. 56).

⚄ Dąbrowski said the usual route of maturation leads to a “premature” integration of mental structures based on “the desire to gain a position, to become distinguished, to possess property, and to establish a family” – “the more the integration of the mental structure grows, the more the influence of the third agent weakens” (1964, p. 57).

⚄ “The third agent persists – indeed, it only develops – in individuals who manifest an increased mental excitability and have at least mild forms of psychoneuroses” (1964, p. 57).

⚄ In ideal, advanced development, the maturational period is “protracted” and “is clearly accompanied by a strong instinct of development, great creative capacities, a tendency to reach for perfection, and the appearance and development of self-consciousness, self-affirmation, and self-education” (1964, p. 57).

⚄ “Because of the third factor the individual becomes aware of what is essential and lasting and what is inferior, temporary, and accidental both in his own structure and conduct and in his exterior environment. He endeavors to cooperate with those forces on which the third factor places a high value and to eliminate those tendencies and concrete acts which the third factor devalues” (1964, p. 53).

⚄ “All such autonomous factors, taken together, form the strongest group of causal dynamisms in the development of man. They denote the transition from that which is primitive, instinctive, automatic to that which is deliberate, creative and conscious, from that which is primitively integrated to that which manifests multilevel disintegration … from that which ‘is’ to that which ‘ought to be’ … The autonomous factors form the strongest dynamisms of transition from emotions of a low level to emotions of a high level” (1970, p. 35).

⚃ 3.5.7.14 The third factor creates a dilemma.

⚄ Dąbrowski recognized that his approach creates a dilemma:

⚅ Where do autonomous forces come from?

⚅ “It is not easy to strictly define the origin of the third factor, because, in the last [traditional] analysis, it must stem either from the hereditary endowment or from the environment” (1973, p. 78).

⚅ “We can only suppose that the autonomous factors derive from hereditary developmental potential and from positive environmental conditions; they are shaped by influences from both. However, the autonomous forces do not derive exclusively from hereditary and environment, but are also determined by the conscious development of the individual himself” (1970, p. 34).

⚄ As third factor grows and development advances, the forces of development become autonomous:

⚅ “The appearance and growth of the third agent is to some degree dependent on the inherited abilities and on environmental experiences, but as it develops it achieves an independence from these factors and through conscious differentiation and self-definition takes its own position in determining the course of development of personality” (1964, p. 54).

⚅ “According to the [TPD], the third factor arises in the course of an increasingly conscious, self-determined, autonomous and authentic development” (1973, p. 78).

⚄ “The genesis of the third factor should be associated with the very development with which it is combined in the self-consciousness of the individual in the process of becoming more myself” i.e., it is combined with the vertical differentiation of mental functions (1973, p. 78).

⚄ “The third factor is a dynamism active at the stage of organized multilevel disintegration. Its activity is autonomous in relation to the first factor (hereditary) and the second (environment)” (1973, p. 80).

⚄ “This approach is close to some of the ideas of Henri Bergson (1859-1941) who maintained that more can be found in the effects than in the causes” (1973, p. 78).

⚂ 3.5.8 Key Constructs.

⚃ 3.5.8.1. Psychoneurosis.

⚄ Definition: “those processes, syndromes and functions which express inner and external conflicts, and positive maladjustment of an individual in the process of accelerated development” (1973, p. 151).

⚄ Dąbrowski saw a positive role for psychoneuroses in advanced development:

⚅ “Connected with the tension arising from strong developmental conflicts” (1973, p. 149).

⚅ “contain(s) elements of man’s authentic humanization” (1973, p. 152).

⚅ Dąbrowski’s approach is almost unique: at odds with the traditional views of Freud, Maslow, and most others.

⚄ Psychoneuroses is a challenging construct in TPD, the term or its derivatives appear some 1560 times.

⚄ “The psychoneurotic may have conflicts in relation to his external environment, but usually his conflicts are internal ones. Unlike the psychopath, who inflicts suffering on other people and causes external conflicts, the psychoneurotic himself usually suffers and struggles with conflicts in relation to himself” (1964, pp. 74-75).

⚄ “Psychoneurotic children clearly demonstrate the large field of disintegration and the great variability of its symptoms” (1964, p. 99).

⚄ The different psychoneuroses form an “inter-neurotic” hierarchy. (see 1972, pp. 109-110).

⚄ “the numerous forms of neuroses and psychoneuroses constitute indispensable developmental processes, then – extending the thus far accepted meaning of the term psychotherapy and treating it as a method of education and self-education in difficult developmental periods, in conditions of great tensions and conflicts in the external environment and in the internal environment” (1967, p. 188).

⚄ “according to our theory we don’t deal here with a psychoneurosis as an illness, but rather with the symptoms of the process of positive disintegration in its multilevel phase,” (1967, p. 195).

⚄ Psychoneuroses “are the protection against serious mental disorders – against psychoses” (1973, p. 162).

⚄ “Emotional and psychomotor hyperexcitability and many psychoneuroses are positively correlated with great mental resources, personality development, and creativity” (1964, p. 19).

⚄ Dąbrowski said don’t try to “help” psychoneurotics, rather, learn from them, appreciate their uniqueness, their creativity, their values, their sensitivity:

⚅ See Dąbrowski’s poem, “Be Greeted Psychoneurotics” (1972). https://www.positivedisintegration.com/greet.pdf

⚃ 3.5.8.2 Adjustment: Four types.

⚄ 1). Negative maladjustment – antisocial, selfish ego dominates behavior that has no regard for social mores:

⚅ Expression of primitive first factor: criminals.

⚅ Unethical CEOs, some politicians (see themselves above law, manipulate laws and others to advance their own personal agenda and satisfaction).

⚅ Level 1(a), primary integration.

⚄ 2). Negative adjustment – “ordinary” socialization:

⚅ “Robotic” and uncritical adjustment to “what is.”

⚅ Conformity to prevailing social norms and values.

⚅ Level 1(b), primary integration: second factor.

⚅ Antisocial and lower impulses are repressed so we can “fit in” (but autonomy is also repressed).

⚅ Adjustment to a “sick” society is to also be sick.

⚄ 3). Positive maladjustment – rejection of what is, in favor of what ought to be:

⚅ Creates crises, psychoneuroses, and disintegrations.

⚅ Initial expression of third factor (autonomy).

⚅ Pits one against social norms and mores – often mislabeled as “ordinary antisocial” maladjustment.

⚄ 4). Positive adjustment – adjustment to a sense of what ought to be: to one’s personality ideal.

⚅ Expression of highest personal values.

⚅ Seen at Level V – secondary integration.

⚅ Carefully evaluated and consciously chosen values.

⚅ Ideal society: everyone is operating at this level.

⚃ 3.5.8.3 Adjustment and the factors.

⚄ Negative maladjustment: Expression of First Factor.

⚄ Negative adjustment: Expression of Second Factor.

⚅ The status quo: society is currently “primitive and confused” (1970, p. 118).

⚅ “The individual who is always adjusted is one who does not develop himself” (1970, p. 58).

⚄ Positive maladjustment: Initial expression of Third Factor (autonomy).

⚄ Positive adjustment: Full expression of the Third Factor.

⚅ “Positive adjustment may be called adjustment to ‘what ought to be.’ Such adjustment is a result of the operation of the developmental instinct” (1970, p. 162).

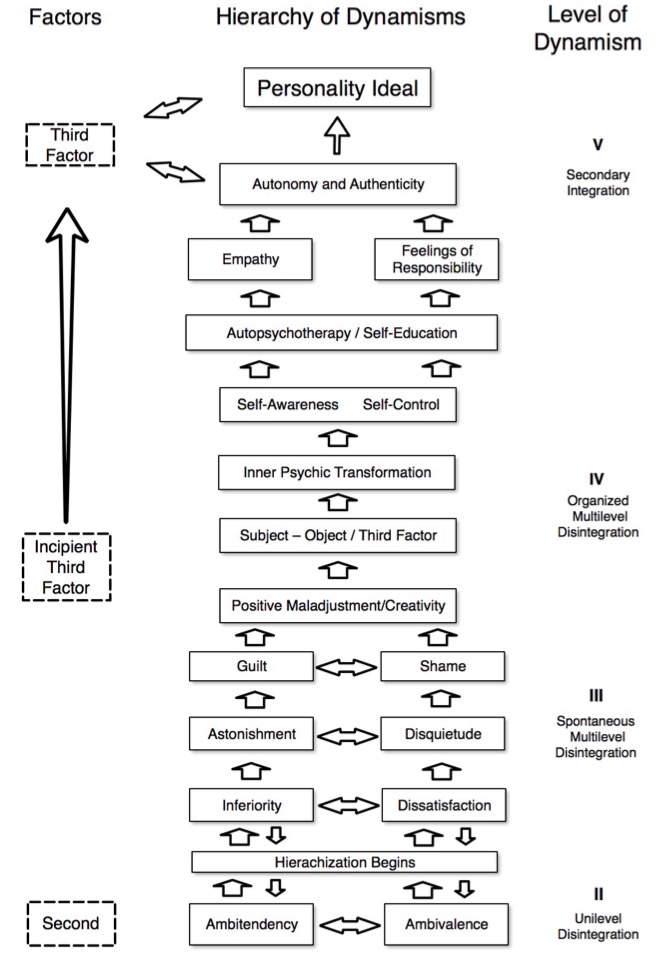

⚃ 3.5.8.4 Dynamisms in TPD.

⚄ Definition: “Biological or mental force controlling behavior and its development. Instincts, drives, and intellectual processes combined with emotions are dynamisms” (1972, p. 294).

⚄ Linked to emotion – from the Latin “emovere” – move through or out – to motivate movement.

⚄ Psychoanalysis is a psychodynamic approach. It refers to the underlying forces that move matter or mind toward activity or progress.

⚄ Dąbrowski used “dynamism” and “instinct” interchangeably: his descriptions of instincts parallel and supplement the dynamisms.

⚄ Dynamisms play a critical role in development and form a major part of the theory.

⚄ Initially act as vague motivators of growth but later, develop and emerge into processes that actively shape and guide development.