Note: this file is based upon an OCR rendering of the original text and may contain typographical errors. As well, this OCR has auto-spelling correction (the manuscripts have multiple spelling mistakes). When quoting material please consult the original image files of the text to ensure accuracy. I have tried to maintain a good approximation of the original materials.

Psychoneuroses is not an illness.

By the same author:

Positive Disintegration 1964

(Little, Brown, and Co.)

Personality Shaping through Positive Disintegration 1967

(Little, Brown, and Co.)

Mental Growth through Positive Disintegration 1970

(with A. Kawczak and M. M. Piechowski) (Gryf Publications)

[unnumbered page]

PSYCHONEUROSES IS NOT AN ILLNESS

NEUROSES AND PSYCHONEUROSES FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF POSITIVE DISINTEGRATION

KAZIMIERZ DĄBROWSKI, M.D., Ph.D.

Professor and Director of Clinical Research and Internship, Department of Psychology, the University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta

GRYF PUBLICATIONS LTD.

LONDON 1972

[unnumbered page]

© All copyrights reserved 1972

Printed by Gryf Printers (H. C) Ltd.—171, Battersea Church Rd.,

London, S.W.11. Gt. Britain.

[unnumbered page]

To my wife Ela—Eugenia

the closest companion of my life and work

with deepest thankfulness

[unnumbered page]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I wish to express my deep gratitude to Dr. Thomas Nelson, Chairman of the Department of Psychology, University of Alberta, whose interest and support of my work has been for me a great source of encouragement.

I wish to thank Dr. John Hooz for his work in improving the English of an early version of this book.

Dr. Michael M. Piechowski, whose collaboration I have enjoyed for the past four years, has given me extensive help in rewriting and reorganizing the early version. The reader owes to his nagging and indefatigable criticism a greater amount of illustrative material than originally present. He is also responsible for the tables. The author, alas, has to confess to a tendency to overlook the need for being more explicit.

The Department of Psychology of the University of Alberta is to be thanked for a grant-in-aid which covered part of the publication cost of this book.

I also wish to take this opportunity and express my gratitude to the Canada Council who as a granting agency has made possible a systematic research, now in progress at the University of Alberta, of different levels of emotional and instinctive functions. The concepts of multilevelness of functions first came out of clinical experience and investigation as described here. Various members of my research team, who in a number of ways contributed to the completion of this book, have also been supported by the Canada Council grant.

Mrs. Janice Gordon has enthusiastically typed and re-typed the manuscript a number of times and also expertly carried the load of handling numerous details in making the book ready for the publisher.

K. D.

Edmonton, June 1971

page vi

PREFACE

In this small book I wish to show that so-called nervousness and psychoneuroses are, in most cases, positive developmental phenomena.

In contrast to this writer’s view that psychoneurosis usually represents a phase of accelerated, authentic development, is the opinion, widely held not only by laymen, but also by physicians, psychologists and educators, that psychoneurosis constitutes an illness. But this latter view, we should note, is derived from a consideration of a relatively small proportion of the psychoneuroses, specifically the really serious psychoneurotic syndromes or those which are on the borderline of psychosis as observed in general or psychiatric hospitals or specialized outpatient departments. Close observation, however, of the broad spectrum of so-called psychoneurotic troubles indicates that most forms of psychic overexcitability, anxiety states, depressions, and obsessions, express internal and external conflicts of deep sensitivity which contribute to the development of autonomy, positive maladjustment and existential attitudes. We may even go so far as to affirm that in most cases the milder psychoneuroses, and these are by far the more numerous, comprise basic prophylactic elements which guard a person against sustaining serious mental illness.

Successful treatment of patients is impossible when they are deprived of their own rich, creative endowment and where the possibility of accelerated development is blocked. Hence, “treatment,” in our view, is not properly conceived as “taking away” the psychoneurotic symptoms and dynamisms. Rather, it is understood as the assistance given

page vii

to a person by encouraging and promoting his development and his carrying on the process of autopsychotherapy. Among the principal obligations of the physician, psychologist and educator, then, is to comprehend in each individual case the congeries of positive functions served by the psychoneurotic dynamisms, and to provide conditions conducive to their development. This too involves providing for the development of creativity, which is closely related to the psychoneurotic structures and functions.

In recognizing the positive basis which the complicated developmental dynamisms provide in conjoint function with the so-called pathological dynamisms, the therapist or consultant may assure the psychoneurotic person of his potential for accelerated psychic development, for a currently difficult but ultimately more attractive and authentic way of life.

It is the task of therapy to convince the patient of the developmental potential that is contained in his psychoneurotic processes. Obviously, to achieve that one has to show him this clearly and precisely on the concrete creative and “pathological” dynamisms that are active in his case.

Psychoneurosis does not represent a first phase of mental illness as proposed by Hughlings Jackson (1927). On the contrary, it constitutes the first and necessary phase of positive, accelerated development and contains the germinal seeds of a rich psychic life.

One has to take into consideration that psychoneurotic patients, and the therapists who treat them, are often under the influence of negative traditions and prejudices which have lasted for many years. In the past and now patients are treated as abnormal, strange, maladjusted and ill.

It may be useful to take a look at the source and causes of the traditional viewpoint which regards psychoneurosis as an illness.

1). It seems that we have not adequately clarified and explained the ancient view on psychoneurosis and the borderline of psychosis. The ancient peoples did not pay

page viii

much attention to the strange behaviour of individuals who—apart from their strangeness—displayed an out-standing power of intuition, ability of foresight and prophetic gifts. These individuals were surrounded by general admiration, respect and were under special protection. The prophetic gift was associated with mental overexcitability, a high degree of empathy, ability of concentration and meditation as well as with some forms of the so-called dissociation of personality. On a close examination there can be no doubt that many of the priestesses in famous temples, some of outstanding monks and members of monasteries were psychoneurotic. Socrates, the towering figure of ancient Greece, is actually considered by many experts in psychology and psychiatry as a psychotic and schizophrenic.

2) In the Middle Ages dogmatism and lack of tolerance were widespread if not dominant. In such an atmosphere the very interest in “novelties,” unorthodox ideas, insubordination to and rebellion against precepts grounded on dogmatism, as well as symptoms of oversensitivity, suggestibility, healing with sorcery—any symptoms of mental dissociation—were regarded as evidence of demoniacal possession.

In accordance with the general emphasis on sin and the possession by good or evil spirits it was possible to put on trial alleged witches and people who refused to accept rigid, a priori system of good and evil.

A many-sided, careful analysis shows beyond any question that most of the victims of medieval persecution were psychoneurotic, people endowed with above average independence of mind, creative talent and intuition.

3. The saints were in many ways similar to this group of victims, although, in most cases, they belonged to another level and dimension. They were usually, included in the domain of the “good,” not only because of miracles and their high standard of spiritual life, but also because of their attitude of self-sacrifice and humility, both qualities being absent in the first group. At any, rate, the saints

page ix

were psychoneurotic, and this opinion is confirmed today by outstanding psychologists, and psychiatrists.

It is being contended here that up to our days we have not moved far from the total misinterpretation of psychoneurotic symptoms which prevailed in the Middle Ages. Although we do not believe today in psychoneurotics being possessed by devils, we condescendingly consider psychoneurosis in terms of mental illness, or at least mental instability. This view seems on the surface to be highly humanitarian; it assumes an analogy with somatic illness. The social status of psychoneurotics is “raised” to the rank of sick people. However, it is in fact a denigration; psychoneurotics are still considered something worse than average, something lower, defective, a failure.

The theory of positive disintegration has been presented in detail elsewhere (Dąbrowski, 1964; Dąbrowski, Kawczak, Piechowski, 1970). Since however, we shall be discussing psychoneuroses in the framework of this theory, I have attempted here to introduce different concepts of the theory in relation to clinical material, rather than giving at the beginning a condensed theoretical outline. This should allow the reader to understand the terminology of the theory as applied to the problems, symptoms and syndromes of psychoneuroses discussed herein. In addition, a glossary of terms has been included at the end.

page x

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Acknowledgments — vi

Preface — vii

I. PSYCHONEUROSES FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF POSITIVE DISINTEGRATION

1. Psychoneurosis as a Process of “Positive” Change of Behavior — 1

2. The Nature of the Psychoneurotic Conflict — 2

3. Psychoneurosis as a Process of Developing a Hierarchy of Values — 3

4. Psychoneurosis as a Growth toward Autonomy — 3

5. The Manifestations of Psychoneurosis and their Social Undesirability — 5

6. The Developmental Potential

(1) Positive development potential

(a) Five forms of psychic overexcitability — 6

(b) Manifestations of the developmental potential in children — 8

(2) The influence of the social milieu on different kinds of the developmental potential — 9

(3) Negative developmental potential — 11

II. FIVE CASES

1. Case 1, W. J — 13

2. Case 2, S. Mz — 26

3. Case 3, S. P — 30

4. Case 4, J. S — 32

5. Case 5, Irene — 35

6. Comparative Analysis of the Five Cases; Unilevel

vs. Multilevel Disintegration — 37

III. NEUROSES AND PSYCHONEUROSES

1. Neuroses and Psychoneuroses as Disorders of Function — 40

2. The Disturbed Function — 43

3. “Arrest” of Development — 43

4. Neuroses and Psychoneuroses: Commonness of Occurrence — 45

5. Classification of Psychoneuroses — 46

xi

IV. PSYCHOSOMATIC CORRELATIONS

1. The Role of Subcortical and Cortical Centers — 49

2. Release of Tension — 50

3. Autonomic Disequilibrium — 52

4. Psychosomatic Disorders — 53

5. Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Tensions — 54

6. Emotions as Disintegrators and Integrators — 55

7. The Etiology and the Level of Psychoneurotic Processes — 56

8. Endocrine Glands — 59

9. Anorexia nervosa — 60

10. Conclusions — 62

V. DISINTEGRATION AND PSYCHONEUROSES IN PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT

1. Psychoneurotic Traits and Positive Mental Development — 64

(1) Enhanced psychic excitability — 65

(2) Tendency toward more of internal conflict and less of external conflict — 66

(3) Psychosomatic sensitivity as an initial condition of disintegration — 67

(4) Internal conflicts are not subconscious repression

but conscious restructuring of different levels of the psyche — 67

(5) Regression as a purposeful behavior — 68

(6) Positive infantilism — 69

(7) Different levels of fatigue — 71

(8) Quietude and solitude as necessary conditions of psychic synthesis and integration — 72

2. The Role of Polarity in the Process of Positive

Disintegration — 73

VI. PSYCHONEUROTIC SYNDROMES ACCORDING TO THE THEORY OF POSITIVE DISINTEGRATION

1. The Expression of Psychic Overexcitability in Psychoneurotic Processes — 77

(1) Limited developmental potential — 78

(2) Strong developmental potential — 78

(3) Strong developmental potential with marked autonomous dynamisms — 80

2. Case 6, S. M — 82

3. Case 7, Z. S — 85

4. Case 8, M. L — 88

5. Case 9, K. J — 91

xii

6. Hysteria — 93

7. Neurasthenia — 94

8. Psychasthenia — 96

9. Psychoneurotic Depression — 98

10. Psychoneurotic Infantilism — 99

11. Sexual Psychoneurosis — 100

12. Psychosomatic Disorders — 101

VII. INNER PSYCHIC MILIEU IN PSYCHONEUROSES

1. Origin and Development of the Inner Psychic Milieu — 103

(1)Unilevel disintegration — 103

(2)Multilevel disintegration: spontaneous vs. organized — 104

(3) The level of psychoneurotic disorders as a function of the

developmental level of the inner psychic milieu — 105

2. Inter- and Intra-Neurotic Hierarchies of Mental Structures and Functions — 107

3. Levels of Functions in Psychoneurotic Syndromes — 115

(1) Psychasthenia — 116

(2) Psychoneurotic obsession — 118

(3) Psychoneurotic anxiety — 119

(4) Psychoneurotic depression — 121

(5) Hysteria — 123

4. Psychoneurotic Dynamisms as Preventive and Immunological Factors — 124

(1) Psychoneurotic sensitivity — 125

(2) Psychoneurotic “unrealism” — 126

(3) The prophylactic role of depressive and hypomanic states — 127

(4) The prophylactic role of isolation and quietude — 128

(5) The prophylactic role of positive regression — 129

(6) The prophylactic character of different forms of hereditary endowment — 130

(7) Pathological versus psychopathic structures — 134

(8) Summary — 135

VIII. PSYCHONEUROTIC OBSESSIONS

1. The Place of Obsessions in Positive Disintegration — 139

2. Classical Theories of Obsession — 139

3. Clinical Cases of Psychoneurotic Obsessions — 141

(1) Moral obsessions — 141

(2) Obsessions of self-destruction — 141

(3) Ambivalence — 142

(4) Obsessions of death — 144

xiii

4. Obsessive Processes in Creativity — 146

5. Janet’s Classification of Obsessions: A New Interpretation — 147

(1) Examples of sacrilegious obsessions — 147

(2) Obsessions and impulsions of criminal content — 148

(3) Genital and sexual obsessions — 150

(4a) Obsessions of shame in relation to oneself — 150

(4b) Obsessions of shame in relation to one’s body — 151

(5) Hypochondriacal obsessions — 152

6. The Therapy of Psychoneurotic Obsessions — 153

IX. PSYCHONEUROSES AND MENTAL DISORDERS

1. Definition of Psychoneuroses — 154

2. Psychoneuroses and Psychopathy — 154

3. Psychoneuroses and Psychoses — 160

4. Schizoneurosis — 167

5. Psychoneurosis, Paranoia, and Paranoid-like Conditions — 172

6. Psychoneuroses and Mental Retardation — 176

X. PSYCHONEUROSES AND OUTSTANDING INDIVIDUALS

1. Definition of Personality — 180

2. Franz Kafka — 181

3. Gérard de Nerval — 186

4. Jan Wladyslaw Dawid — 190

5. Ludwig Wittgenstein — 193

6. Psychoneurotic Dynamisms and Personality Development — 194

7. The Role of Creative Dynamisms in Psychoneuroses and Types of Development — 197

(1) Creative dynamisms in unilevel and multilevel disintegration — 197

(2) Types of psychoneuroses and types of creative abilities — 199

XI. SUPERIOR ABILITIES AND PSYCHONEUROSES IN

CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE

1. Methods and Subjects — 202

2. Definition of Some Concepts — 204

3. General Characteristics of the Children Examined and Individual Examples — 205

(1) Case 15 — 207

(2) Case 16 — 208

xiv

4. The Inner Psychic Milieu and the Kinds and Levels

of Psychoneuroses in Young People with Superior Abilities — 211

5. Conclusions — 218

XII. THEORIES OF NEUROSIS AND THEORIES OF DEVELOPMENT

1. Psychoneurosis as a Prelude to Mental Illness — 220

2. Psychoneurosis as an Organic Disorder — 221

3. Regression and Emotional Immaturity as the Source of Psychoneurosis — 221

4. Psychoneurosis as a Disorder of the Reality Function — 222

5. Subconscious and Unconscious vs. Conscious Conflict in the Genesis of Psychoneurosis — 226

6. Adler: Asocial Compensation for Feelings of Inferiority — 231

7. Jung’s Conception of Psychoneurosis and Development — 235

8. Karen Horney: Psychoneurosis as a Childhood Trauma — 243

9. Specific Crises at Successive Stages of Development — 244

10. Lindemann: The Role of Crises in Personality Development — 246

11. Therapist-Client Relationship as a Condition of Growth — 246

12. Psychoneurosis as a Failure of Self-Actualization — 247

13. Psychoneurosis as a Consequence of Guilt — 249

XIII. PSYCHOTHERAPY OF PSYCHONEUROSES

1. Principles — 252

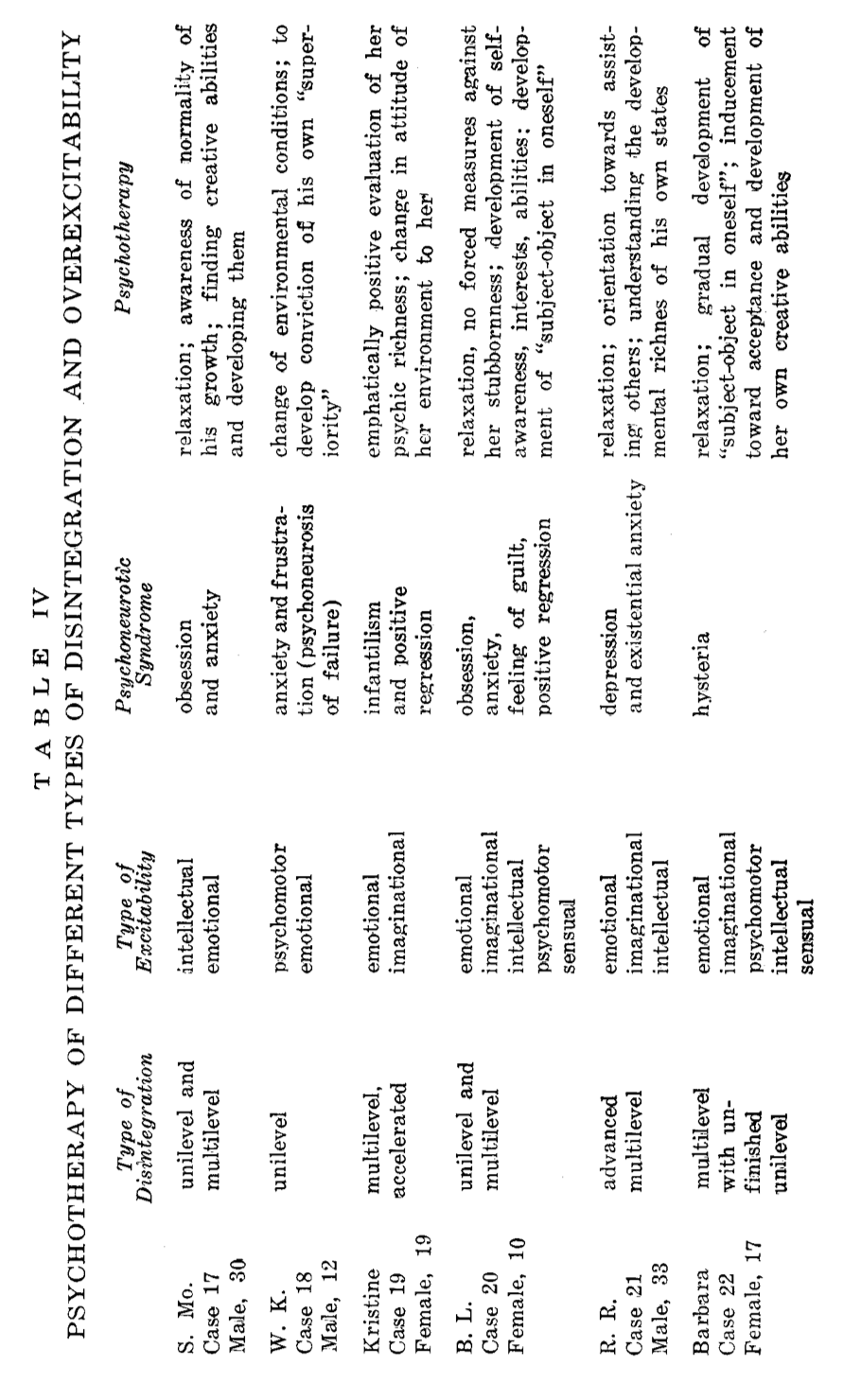

2. Individual Cases and Treatment Programs — 256

(1) Case 17, S. Mo — 260

(2) Case 18, W. K — 265

(3) Case 19, Kristine — 270

(4) Case 20, B. L — 273

(5) Case 21, R. R — 276

(6) Case 22, Barbara — 281

3. Comparison of Psychotherapeutic Programs — 284

GLOSSARY — 289

BIBLIOGRAPHY — 307

INDEX — 313

xv

Be greeted psychoneurotics!

For you see sensitivity in the insensitivity of the world,

uncertainty among the world’s certainties.

For you often feel others as you feel yourselves.

For you feel the anxiety of the world, and

its bottomless narrowness and self-assurance.

For your phobia of washing your hands from the dirt of the world,

for your fear of being locked in the world’s limitations,

for your fear of the absurdity of existence.

For your subtlety in not telling others what you see in them.

For your awkwardness in dealing with practical things, and

for your practicalness in dealing with unknown things,

for your transcendental realism and lack of everyday realism,

for your exclusiveness and fear of losing close friends,

for your creativity and ecstasy,

for your maladjustment to that “which is” and

adjustment to that which “ought to be,”

for your great but unutilized abilities.

For the belated appreciation of the real value of your greatness

which never allows the appreciation of the greatness

of those who will come after you.

For your being treated instead of treating others,

for your heavenly power being forever pushed down by brutal force;

for that which is prescient, unsaid, infinite in you.

For the loneliness and strangeness of your ways.

Be greeted!

xvi

CHAPTER I

PSYCHONEUROSES FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF

POSITIVE DISINTEGRATION

1. Psychoneurosis as a Process of “Positive” Change of Behavior

The majority of psychopathological conditions, such as nervousness, neuroses and psychoneuroses, are—from the standpoint of the theory of positive disintegration—behavioral patterns of inner, mental changes of a positive character (Dąbrowski, 1964; Dąbrowski, 1967; Dąbrowski, Kawczak and Piechowski, 1970). By “positive” we imply here changes that lead from a lower to a higher (i.e. broader, more controlled and more conscious) level of mental functioning. The process of change may involve mental disharmony, loosening of functions or even mental disorder. Such phenomena as disquietude, astonishment, anxiety, or dissatisfaction with oneself, feelings of inferiority regarding oneself, fear, guilt, certain obsessive or ecstatic conditions, exaggerated control of oneself, strong introvertive tendencies, etc., are processes which often indicate positive changes in building a new inner psychic milieu.

The so-called disturbances of inner feeling (coenesthesia), and dystonia (i.e. disturbances of the autonomic nervous system) may constitute certain primitive requirements giving rise to those conditions which are conducive to self-observation and result in a change of attitude towards oneself.

A profound knowledge of oneself and a deep level of emotional experience, as well as a more meaningful contact with the environment seems to be impossible without going through conflicts, disharmony, intensified sensitivity, and even organ-

1

is or mental illness. While it is true that certain internal somatic or neurological disturbances exhibit symptoms similar to psychoneurotic symptoms, there are as yet no sufficient grounds for deducing a somatic etiology in psychoneurosis in general. In our opinion the latter view is an erroneous oversimplification. The tendency to treat psychoneuroses as being symptomatic of the first phase of a more serious mental disease as postulated by Jackson (1958) and supported by other authors (Sargent and Slater, 1954)—can no longer be maintained.

2. The Nature o f the Psychoneurotic Conflict

A great majority of Psychoneuroses represent “positive disorders”; they are psychogenetic (i.e. originating in the psyche), and are often expressive of rich personality nuclei in individuals capable of developmental, even accelerated, change. They are expressive of conflict between an inner personal milieu, and the outer milieu, precisely because they exhibit tendencies towards a concern for that which “ought to be” instead of adjustment to that “which is.”

Psychoneuroses are observed in people possessing special talents, sensitivity, and creative capacities; they are common among outstanding people. Psychoneurotic syndromes are not found among those who are moderately or considerably mentally retarded. With all due regard to present general medical, neurological or endocrinological methods of treatment, in our opinion it is essential that psychologists and psychiatrists do not reduce Psychoneuroses to organic factors. Rather it is our main task to understand them as representing an individual complex evolution of conflicts. These conflicts yield positive effects, i.e. their outcome is individual growth, and it is our task to see also their other aspect, i.e. as difficulties in contact with the environment, or opposition to pt, when invariably it is the psychoneurotic individual that is morally superior to his environment, and therefore cannot adjust to it. Thus we find both inner and outer collisions in individuals who are characterized by constitutional elements of positive or even accelerated development.

2

Psychoneuroses should be approached from both psychological and neurological viewpoints in regard to their etiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. This is already evident from the mere consideration of the meaning of the term itself: psychoneurosis. Furthermore it is necessary to ask what developmental functions are involved. What protective mechanisms have appeared in connection with these “disorders,” in both the inner and outer milieus. What values have been shaken in their hierarchy, and what have been the attempts of the individual to recover them, or to exchange them for higher or lower values.

3. Psychoneurosis as a Process of Developing a Hierarchy of Values

“Psychoneurotic experiences” by disturbing the lower levels of values help gradually to enter higher levels of values, i.e. the level of higher emotions. These emotions becoming conscious and ever more strongly experienced begin to direct our behaviour and bring it to a higher level. In this way higher emotions play a dynamic role in our development and give meaning to our life. As new and higher values the higher emotions slowly begin to shape our “new harmony” after the collapse of the primitive harmony of lower level. The problem of value is essential and emerges sooner or later in each case of psychoneurosis.

The problem of the meaning of life and of authentic thinking and feeling is also common and outstanding. Hence the psychoneurotic problem is one of the lack of adjustment manifesting protest against actual reality, and the need for adjustment to hierarchy of higher values: to adjust to that which “ought to be.”

4. Psychoneurosis as a Growth toward Autonomy

The feelings of internal discard (subject-object in oneself, feelings of dissatisfaction with oneself and guilt, are common experiences in life. Guilt feelings here do not stem from a repressing action of the “superego”; neither do they have to be an

3

expression of real guilt of the psychoneurotic patient. They indicate rather an excessive sensitivity to the inner milieu, in which there appears, concomitant with a tendency for accelerated development, a sense of inferiority in relation to oneself, a feeling of having “wasted” one’s possibilities for fulfillment, of having betrayed one’s ideal, and an exaggerated perhaps sense of personal responsibility. Hypersensitivity—whether internal or external—may be, and often is, out of proportion to the real guilt.

Psychoneuroses—especially those of a higher level—provide an opportunity to “take one’s life in one’s own hands.” They are expressive of a drive for psychic autonomy, especially moral autonomy, through transformation of a more or less primitively integrated structure. This is a process in which the individual himself becomes an active agent in his disintegration, and even breakdown. Thus the person finds a “cure” for himself, not in the sense of a rehabilitation but rather in the sense of reaching a higher level than the one at which he was prior to disintegration. This occurs through a process of an education of oneself and of an inner psychic transformation. One of the main mechanisms of this process is a continual sense of looking into oneself as if from outside, followed by a conscious affirmation or negation of conditions and values in both the internal and external environments. Through this constant creation of himself, through the development of the inner psychic milieu, and development of discriminating power with respect to both the inner and outer milieus—an individual goes through ever higher levels of “neuroses” and at the same time through ever higher levels of universal development of his personality.

In order to better understand this approach and to see it realized, an attitude needs to be developed among doctors, among patients themselves, and among those affecting their environment, that “patients,” rather than being manifestly “cured,” should be provided with conditions conducive to their development. Psychoneurotics, rather than being treated as ill, should be considered as individuals most prone to a positive and even accelerated psychic development.

4

Restoration or re-elaboration at a higher level of a patient’s personality is the postulate of existential psychotherapy (May, 1961; Laing, 1965, Frankl, 1967), of “integrity therapy” (O. H. Mowrer’s psychotherapy which allows the integration of personality through sincere and open “confession of guilt” in a psychotherapeutic group, Mowrer, 1964), and the theory of positive disintegration, although in each case expressed differently.

5. The Manifestations of Psychoneurosis and their Social Undesirability

The terms neurosis and psychoneuroses are used every day. It is common in industrial settings to ascribe work absenteeism to such reasons. The general practitioner is quite familiar with this problem. When the physician cannot find organic changes underlying various subjectively unpleasant experiences of daily life, personal difficulties, bad feelings or various symptoms, they are then attributed to neuroses.

All states which appear to be unwarranted by existing external conditions, such as: anxiety, states of nervousness (i.e. increased psychic sensitivity), obsessive thoughts related to an apparent danger for us or for our children, intense emotional fatigue or depression, “nervous sleep,” hypersensitivity, an increase in rate and strength of heart beat, etc., are universally considered by a majority of physicians, specialists or not, as manifestations of neuroses or psychoneuroses.

On the one hand there is a general—and largely correct conviction—that neuroses and psychoneuroses are not grave conditions, and do not lead to the dissolution of mental functions. In most cases they still permit the continuation of one’s work, albeit less effectively. On the other hand it must be recognized that they are a nuisance, cause fatigue, weaken one’s positive approach to life, etc. They prohibit or limit a pleasurable outlay of energy, they weaken or close—at least periodically—a proper contact with our environment, and cause much difficulty in both our home and professional lives. We know that during various

5

social changes or upheavals, such as post-war periods of great tensions and instability, the number of disorders of this kind increases considerably. A social security report from Zurich shows that less than ten years after the Second World War about 70 percent of all patients were cases of neurosis or psychoneurosis (Brun, 1954), Similar percentages are found in out-patient clinics in England, France, Poland and other countries while in the United States only 20 percent of the people were found to be free of signs of emotional distress (Srole, Langer, Michael, Opler, and Rennie, 1962), and one third of a small town population was found to have distressing psychiatric symptomatology (Leighton, 1956).

What is the basis of these disorders, what are their causes, their development and their outcome? We shall try to give an answer in the pages to come. We shall also try, as already indicated, to shed some light on the positive correlation between accelerated development, creative tendencies—and neuropsychic complexes.

Before presenting some clinical material we have to introduce the concept of the developmental potential.

6. The Developmental Potential

In the great majority of cases of psychoneurotic “constitution” the author sees present, more or less clearly, nuclei of a positive developmental potential. In many cases this potential is of the kind that predisposes the individual for an accelerated development, for the development of his talents, or for the development of an eminent personality.

It is our opinion based on extensive experience that there is never, or almost never, a case of accelerated development, and even more so of eminent development, without a psychoneurotic constitution.

(1) Positive developmental potential.

(a) Five forms of psychic overexcitability.

The main form of the positive developmental potential are five kinds of psychic overexcitability namely, sensual, psycho-

6

motor, affective (emotional), imaginational and intellectual. Each form of overexcitability points to a higher than average sensitivity of its receptors. As a result a person endowed with different forms of overexcitability reacts with surprise, puzzlement to many things, he collides with things, persons and events, which in turn brings him astonishment and disquietude. One could say that one who manifests a given form of overexcitability, and especially one who manifests several forms of overexcitability, sees reality in a different, stronger and more multisided manner. Reality for such an individual ceases to be indifferent but affects him deeply and leaves long-lasting impressions. Enhanced excitability is thus a means for more frequent interactions and a wider range of experiencing.

An individual who is excessively sensitive sensually possesses a more or less superficial sensitivity to beauty, is suggestible, is more exposed to the difficulties of life. An individual who is psychomotorically overexcitable is restless, curious, cannot sit still in one place, wanders around, has an insatiable need of change and of “wandering into space.” An individual who is emotionally overexcitable is sensitive, takes everything to heart„ is syntonic and even more often empathic though not necessarily in a highly developed manner. He has a need of exclusive and lasting relationships, of help and protection, of understanding suffering. An individual who is overexcitable in respect to imagination is sensitive toward “imaginational realities,” is usually creative, has vivid fantasy and is often full of ideas and plans. He displays abilities in poetry, art or music. He has his “kingdom of dreams and fantasy.” An individual intellectually overexcitable shows strong interests early in inner and in external life, has strong nuclei of analysis and synthesis. Early in life he is capable of asking questions and demanding logical answers.

Some forms of overexcitability constitute a richer developmental potential than others. Emotional (affective), imaginational and intellectual overexcitability are the richer forms. If they appear together they give rich possibilities of development and creativity. If these three forms of overexcitability are combined with the sensual and psychomotoric then these latter two are

7

both enriched and enhanced in their positive developmental possibilities.

(b) Manifestations of the developmental potential in children.

Almost all these forms of overexcitability can be detected between 1 and 2 years of age and the older the child the more they are discernible. We can note these potentials in an excessive and global mobility of the child, in its sensitivity to colours, sounds, tastes, smells, in its need for affection, fondling, in silent moods, early sadness and spontaneous joy, in early syntony—even empathy—far parents and siblings, in richness of observation, in quick penetration into the world of fantasy and imagination, in early reflection about himself, about life and about death. Such reflections can appear already in children 3-4 years, old. For instance, one four-year-old girl said. “Death is a trip but it is hard to get out of the hole in the ground where they put the dead person.” The same girl also asked: “How can you tell whether someone is sleeping or dead?” Another five-year-old girl created for herself whole new realms of existence with leprechauns, birds, squirrels. The door to the attic was the door to these realms which appeared to have a character of sacred mysteries.

Developmental potential can also be observed in children in connection with strong special interests and abilities. If a child has enhanced intellectual excitability then at the age of asking questions he will not be satisfied with automatic answers but will ask a second and a third time, often forming the questions in a new way as a result of new associations. Some children are surprising by their perceptiveness of the world around them, by their childish “philosophical” outlook. Some children show early mathematical abilities in relation to mathematical-philosophical and magical problems.

There is a great number of children who at the age of 4-6 write poetry distinguished by deep content and good form. One six-year-old girl when asked by her mother whether she did not get tired by dancing so often answered: “Mother, I don’t get tired because I don’t dance, it’s only my feet who do the

8

dancing.” In this expression we can see besides a marked refinement of thought, a nucleus of the development of the inner psychic milieu, initial forms of the dynamism “subject-object in oneself” and a developmentally significant dualistic attitude (a manifestation of different levels of experience).

These nuclei of the inner psychic milieu together with psychoneurotic elements appear in the feeling of shame, which is much stronger than usual, in the feeling of guilt when the child has caused sorrow, and in a desire to make good. In such experiences there is frequently hidden the germ of an ideal which in its main outline the child has developed on its own, whether with the support of, or against, its environment. Quite often the child shows some dissatisfaction with himself and is feeling different from what he thought he was and what his parents thought he was. Here is the beginning of an interaction between the developmental potential and the influence of the environment.

A separate group of the nuclei of the developmental potential (although not strictly isolated from the above) are traits which later in life are called neurotic. Such is for example an excessively strong exclusivity of attachment to close persons, fear of their falling ill, longing for their return when they are away. Such are for instance phobias of contact with certain animals like earthworms, lizards or snakes; phobias of dirty water, unknown situations in the environment, possibility of disappointment, and symptoms of neurotic expectation, etc.

(2) The influence of the social milieu on different kinds of the developmental potential.

It goes without saying that the constitutional nuclei are highly modulated positively or negatively by the social milieu.

When the developmental potential is very strong and very rich even a negatively acting social milieu is of secondary importance. If the nuclei of the developmental potential are weak, or if they also contain some negative components then the character of the social milieu is of decisive significance. If it is nourishing then individual growth will be supported where

9

it is lacking in its natural endowment, if it is negative then severe pathology is most likely. If the developmental potential has distinctly negative character then the influence of the social milieu is without much significance.

Besides the constitutional endowment expressed as nuclei of the developmental potential and the influence of the social milieu there is a third category of forces that is very important in the shaping of psychoneurotic processes. These are the autonomous factors which develop gradually throughout the individual’s life experiences. Becoming more and more conscious they often come to play the most important role in the evolution of psychoneurosis as a growth towards autonomy and self-determination. These autonomous factors find their expression in education of oneself, in autopsychotherapy, and in richer use of the individual’s creative abilities.

In individuals whose developmental potential is more limited and who also present low psychic resilience because their developmental nuclei are somewhat weak, the stereotyped social influence reduces their abilities for creativity for the sake of adjustment and may lead to negative disintegration. In individuals who are richly endowed and talented the same influence leads to psychoneurotic creative processes which, although rich in their content, are described by the social milieu and the physicians as pathological. Such a label is, of course, detrimental to both the psychoneurotic individuals and the society. In this, way the path of collisions between psychoneurotics with their creative components and the environment takes shape. The path of these collisions is a hard road of liberation for creative individuals, it is a path of suffering—not always necessary and not always useful. It is a path which does not quickly lead to finding one’s own road of development because of the strong inhibitions and frequently high suggestibility of these individuals.

These different forms of the psychoneurotic developmental potential constitute in their totality the “royal path” of hierarchical development—through multilevel disintegration, inner conflicts, creative instinct and instinct of self-perfection—toward secondary

10

integration, i.e. toward the united, harmonious and highest spiritual reality which is liberated from lower levels of the unconscious and in which one experiences contents previously known consciously but only intellectually (i.e. without the dynamic participation of higher emotions).

(3) Negative developmental potential.

In a significant number of cases of isolated forms of sensual or psychomotor overexcitability (i.e. when there is no admixture of other forms of overexcitability), in cases when the nuclei of the inner psychic milieu, wider interests and abilities, and sharp awareness of one’s own developmental path are lacking, we are dealing with a negative potential which is not helped by the influence of the environment, but on the contrary, is harmed by it.

It is difficult to speak of a negative psychoneurotic potential because a negative developmental potential covers the borderline of psychoneurotic nuclei, psychopathy, psychosis and even mental retardation. When enhanced psychomotor and sensual overexcitability is combined with strong ambitions, tendencies to showing off and lying, it constitutes a nucleus of psychopathy with some neuropathic components. This is a potential for the development of characteropathy, or, better, of hysterical psychopathy.

Tendencies toward disintegration with very limited or quite absent activity of the developmental instinct, and with a greater strength and number of disintegrating dynamisms over the integrating ones, are found in the potential on the borderline of psychoneurosis and psychosis. On the borderline of mental retardation and psychoneurosis (or, rather, neurosis) the developmental dynamisms appear weak pointing to a very limited developmental potential.

These forms of the developmental potential—insufficient for positive development—may be called abiotrophic to denote the absence or degeneration of the normal functions of the organism, in this case as applied to mental development.

11

We can summarize as follows

(1) The presence of neurotic or psychoneurotic positive developmental potential guarantees creative development through higher forms of psychoneurotic processes such as internal conflicts, hierarchization, development of autonomous and authentic dynamisms, towards a high level of personality and secondary integration,

(2) Developmental potential which is not universal and of weak tension may lead either to positive development through nervousness and psychoneuroses, or to negative disintegration, psychosis or suicide. The environmental influence is to a very great degree responsible for the path which will be taken.

(3) A separate obstacle for both groups of individuals with developmental potential either (1) or (2) is the established attitude of society, when physicians and psychologists treat psychoneurotics as abnormal, and worst of all—sick. This attitude is primarily responsible for inhibition, isolation, noncreative feeling of inferiority and lack of a creative and rich development. These conditions create collisions between their creative inclinations timidity, and lack of self-confidence; they create the loneliness of psychoneurotics.

12

CHAPTER 11

FIVE CASES

The following discussion of several clinical cases is intended to give the reader an introductory orientation as to the kind of neurotic disorders characteristic of the processes of positive disintegration as well as to the manner of interpretation and diagnosis. This will serve as a basis for psychotherapy based on the theory of positive disintegration.

Case 1

W.J. was a young housewife approximately 30 years old. When she came for therapy I asked her to write in some length her life history, which she did submitting a manuscript 35 pages long. She had no important history of pathological hereditary endowment, since neither her parents nor her grand-parents and other close relatives suffered from psychosis, mental retardation or psychopathy. She had a happy early childhood, a quiet home, care and love of her parents, which contributed to her feelings of security. As a child she believed that her mother was able to deal with any potential danger. The patient had still greater respect for her father and avoided offending, him in any way. From early childhood she was shy and although she never had bad experiences with animals, she was afraid of them, especially dogs and cats. She was afraid of being bitten by a dog, being kicked by a horse, or being attacked by a cow.

She said that even as a child she was an egoist. If she had something to share with her younger sister, she used to take the larger part. When she went with her father, brother, and

13

sister for a sleigh ride, she wanted her brother to go first, and only when he came out safely would she then go herself. She writes that she was never a joyful child, but was rather inclined to emotional reactions, melancholy and sorrow. Further she says that when she was only 5 years old, one of the elder boys asked her mother why she always had such a sour look on her face.

In spite of her statement as to her lack of a joyful attitude, the patient maintained that she took pleasure in playing with other children. But this joy was often stifled through excessive caution or fear of falling down, bumping into something, or bringing some calamity upon herself. She was very much aware of her sister’s several minor accidents while playing and the subsequent anxiety at home, doctor’s visits, treatment, etc. When she was six years old her first encounter with an accident left on her very strong impression. She saw an ambulance and a woman lying on a litter covered with something white. She vomited at the sight and then fainted. Later she always experienced nausea following an emotional upheaval.

The patient also had considerable trouble in facing new situations. She did not want to go to kindergarten; then while going to school she became excited and cried spasmodically. She had no sense of duty in the preparation of her lessons, so she often played all day. Only in the evening did she make up her lessons. When her parents once decided to give her no help in their preparation, she stayed up till 11 o'clock at night, cried during the lesson, and thought of various punishments for her parents, including her own death.

All these unhappy events and physical reactions promoted an attitude of anxiety. She felt strong anxiety regarding the fate of her parents, especially her mother. When she was seven she felt deeply concerned about her mother’s surgical operation, even though it was a mild case and was performed in an outpatient clinic. At that time she lied cross-like on the floor and prayed very long for a successful operation. At another time she had a shocking experience when her father had a heart attack and lost consciousness. She was frightened, went pale and trembled all over. However, when facing an accident, she could at times con-

14

trol her feelings to the extent of participating in caring for the wounded. At the age of 10 or 11, when her mother was absent she prayed ardently for her happy return. During the time of her mother’s absence, she took her mother’s nightshirt to bed since she somehow felt better that way.

At ten she had scarlet fever and tried to extend for as long as possible the convalescent period at home because here she felt most secure. Following this sickness she went to school but suffered from anxiety and feelings of insecurity. She changed her grade school several times without evident reason. Each time the school she attended became unpleasant or obnoxious to her, she asked her parents to transfer her to another school under such pretexts as needing a location closer to home, higher standard of learning, etc.

She liked very much to participate in a school theatre or play with other children in the backyard. Usually she assumed the function of an impresario and played a male role. She wrote literary scenarios based on fairy tales. Those artistic activities gave her much joy; she also wrote verses and novels, and dreamt that some day she would see her books on library shelves.

She deeply felt the period of the uprising.* Her reaction to those events often included vomiting. About that time, too, she witnessed her father’s arrest by the Germans. Following a moment of stupor she ran screaming towards her father and the German patrol, and felt like throwing herself on them in defense of her father, but did not. One may note here that when her altruistic feelings (concern for her father) reach very high tension then her whole psyche becomes well organized. This points to distinct developmental possibilities.

She was terrified when she found herself, accidentally, in the front line of battle facing bombings, wounds, and death. In recalling those events after several years, she trembled nervously. Passing from the knowledge of an approaching imminent

_____________________

*The Warsaw uprising of 1944, when most of the city was destroyed.

15

danger (house searches by Gestapo, arrests of neighbours and the like) to the realization that the whole family was safe, she got a fever.

While attending high school she tried to look more mature than she was in order to capture the attention of her elder colleagues. At this time she used to write for a school paper and participated in a school theatre. This was a very enjoyable period for her. She belonged to girl-guides but avoided going to camps, for she was afraid to leave the home milieu.

She was strongly aroused emotionally during flirtation, and her first kiss left her unconscious. She was rather infantile and at that time no further physical contacts were made. Following this event she looked upon herself as a mature woman, but had guilt feelings in relation to her mother who had impressed strong moral principles upon her. That evening she dreamt of an ideal boy—a husband—she imagined a beautiful house, marriage, nice children, and that she was madly in love with her husband. At this time, she had outbursts of anger, crying, and periodic anxiety with momentary numbness of the hands. During this time, too, she was supposed to take part in a show, in a solo scene, but she panicked and refused to play the part.

At one time she became weak during a lecture-twice in the same day. Physicians directed her to take tests, and she went through them with anxiety. She felt ill all day before the tests, and at night she rose up with a cry and took to the corridor. She felt that she was falling down and saw her mother as if from very far. After this event, which she called “an attack,” she experienced trembling of her whole body. This event also aroused new forms of anxieties, especially in connection with the possibility of a repetition of the attack. So she did not want to leave home, and she stopped going to school. For many weeks she appeared very weak. She then had another attack of this kind, but much milder.

At that time she was seen by many physicians. She stayed in bed a long time, and when she tried to get up, experienced dizziness and tingling in the feet; so she no longer got up.

16

Numerous clinical tests were made. She received injections of neurotonine (a medicine for toning up the nervous system). Still the fears did not dissipate and she never went out by herself. She kept away from school for fear of another “attack.”

Following some weeks of rest her condition was improved and she resumed going to school. However, she awaited the end of every lesson with trembling. She went from physician to physician seeking a remedy. Finally on a neurologist’s advice she was placed in a ward for neurotic patients. After psychotherapeutic and tranquilizing treatment her strong fears were dissipated, but she developed, she said, a fear of a mental disease. She maintained that she found shock treatment very hard to bear and had very strange feelings during that treatment. Specifically she did not like to see herself in a mirror. She was constantly afraid of becoming mentally ill. Following her return to school, she again became afraid of an oncoming “attack.” But these fears were now less severe. The patient again intended to stop her school attendance, but during these periods of doubts there appeared new circumstances. She found compatible associates and engaged in sports. This gave her considerable self-assurance; she found an outlet in skating and ball games.

At that time she fell in love which greatly absorbed her. She was 18, it was a good year. Conditions at home were good; she was well liked at school; she worked socially, and was in love. Once, however, she fell ill with influenza, after which she felt bad again, and felt overworked because of her approaching graduation from high school and excess of social activities (school drama in particular). She then experienced a very strong feeling of estrangement. Although feeling ill, she still prepared for finals and passed very well. Immediately after, she took insulin treatment at a local clinic and this had a favorable effect on her general well-being. Later she entered into a sexual relation with her fiancé which gave her much pleasure, but she was physically disappointed mainly due to her inability to reach an orgasm. She loved her fiancé, respected him highly, but at the same time had pangs of conscience towards her

17

mother who did not suspect that she was living with him. During this period she felt better, then again worse, and was almost constantly bothered by feelings of estrangement of varying intensity. About that time she married her fiancé. Rather soon, however, she met someone else for whom she felt an emotional attraction, and the attraction was mutual. Still, moral bonds did not permit any rapprochement. At this time, most fears disappeared for as much as a four year period. In this period of her life moments of great joy and general satisfaction acted as a force that pulled her together and subordinated her disintegration to constructive trends.

Both her continued studies and those of her husband did not allow them to live together. During this time the patient became pregnant. New conditions, independent professional work, and living with her husband in a new home of their own gave her much joy. She became satisfied with life. Her one worry was being away from her parents. She had much anxiety in respect to her pregnancy, especially when nurses told her of many cases of delivery unfortunate for both mother and child. However, the birth was quite regular. After childbirth the patient became fearful for the child who, she believed, could die at any moment. From the start she was a loving mother, forgetful of her own needs, and completely absorbed by her feelings for her child. From this and other observations, we see that she was ambivalent in her very egocentric and alterocentric changes of attitude.

Many difficulties arose due to bad relations between her husband and her mother. They were very different and disliked each other. Often there developed a feeling of two enemy camps between her parents and her own home. This situation troubled her very much. This unpleasant climate reached a critical stage when, following a family quarrel, the husband took his belongings and left to live with his parents. The patient then went through a nervous breakdown. She went through states of strong anxiety with strong psychosomatic reactions like being cold, going pale, etc. At times she went rigid or was in stupor.

When she was with her husband and child, or separately

18

with her parents, she felt very well. But when all were together, she felt very tired. Then her old fears returned. Once she went to bed with influenza after which her fears increased together with the feeling of estrangement. About this time, too, one of her friendly relatives died. From then on fears of death became prominent and the feeling of estrangement was intensified. This condition was somewhat improved after the use of Miltown (Meprobamate) and following a family vacation trip. She felt she was being cured. Soon after, however, she fell ill with nephritis, and fear symptoms reappeared. Her feelings of insecurity were increased by an atmosphere of resentment between the two family camps.

These reactions indicate that W.J. was much under the influence of her environment which pushed her towards positive or negative feelings. Since most of the time we do not observe in her autonomous dynamisms (consciousness, internal conflict) we can say that her developmental potential is limited in its expression.

With the coming birthday of her father, she attempted to influence her husband to come and wish him a happy birthday; her husband refused and this caused difficult moments for her. She had feelings of becoming insane. She did not sleep all night, and then had a nervous breakdown, similar to the previous one. She cried that she was dying; she felt her heart coming to a stop, and felt that she was losing consciousness. Electrocardiograph examinations showed no anomaly.

When her husband left for a few months to work out of town she felt a favourable decrease of tension in spite of all her true feelings for him. However, after a time her fears returned, especially her sense of estrangement and general weakness. An improvement in the family financial situation, the patient thought, would bring recovery of her health. But this was not the case.

At my request W.J. described her own character as that of a person universally sensitive with a sense of beauty for the world around her and possessing a certain fear before the forces of nature. She expected much attention from her parents and others to make her life easier. She spoke of herself

19

as having a tendency to be lazy, of being rather neglectful of her duties„ unsystematic, careless, and without internal discipline. She admitted a desire to be in the limelight, but without having to earn it; she lacked sufficient interest in the needs of others and looked at the world only from the viewpoint of her own self.

This opinion about herself indicates that she has the potential for an objective, negative, even sincere evaluation of herself. This points to certain potential in her to develop an attitude toward herself as object as well as to be capable of some initial process of inner psychic transformation.

A vivid imagination combined in her with a tendency towards an intense living of happy moments, looking for real fulfillment. However, she always lacked something which deprived her of reaching a full measure of satisfaction. According to her own account, she was not independent enough, since she needed to lean on someone emotionally, earlier on her mother, now on her husband. She said that some of her character traits were changed favourably under her husband’s influence; she became—in her words—more industrious and submissive, less hysterical (in the popular sense), and more attentive to her environment. On the other hand she thought that her husband could be a cause of her wavering confidence in her own resources, for he commonly told her how wrong she was. In her account she emphasized the divergence between dreams of happiness, wealth, great personal attractiveness, elegance, intelligence, and the reality which failed to fulfill those dreams. She thought that the change of atmosphere from that of a warm home environment to the challenging and difficult conditions of a mature life had increased her physical tension and fear of reality. This was connected in her mind with further fears of sickness and death.

The following conclusions about the presented material characterize some very important psychoneurotic traits.

1. W.J. is characterized by increased imagination and high emotional sensitivity. In this respect, every unpleasant experience provides a reaction out of proportion to the

20

stimuli; the degree of trauma caused by those stimuli is felt to be much greater than among so-called normal individuals. Because of that she showed an increased susceptibility to frustration.

2. W.J. grew up in a soft, even spoiling, climate at home. This together with her innate traits of sensual, emotional, imaginational overexcitability and egocentrism made her unprepared for the demands and responsibilities of marriage, which was for her too hard to adjust to.

3. Under conditions of great disharmony between the pressure of the external milieu and a poorly developed inner psychic milieu she lost the sense of proportion and balance in handling everyday affairs (weakening of the reality function). In consequence she developed fears. These fears or anxieties of indefinite character resulted in disintegration of her psychic unity. She was constantly worried “what is it going to be like,” she was worried about her appearance, she was afraid of an irregular pregnancy, she was afraid she would go, mad. These easily excited emotional tensions point to an enhanced excitability of imagination, affect and sensuality. Such enhanced excitability is the basis for a more intense perception of certain aspects of reality, hence for more anxiety. In consequence there is fear of these “other” aspects of reality and anxiety connected with the anticipation of that fear.

4. The patient possessed the capacity for easily transposing emotional experiences into the autonomic nervous system, manifested as spasms of the coronary vessels and disturbances of inner sensations (heart beating, nausea, head-aches, fainting, etc.). The attendant feeling of changes in personality structure manifested themselves in fears, especially of personality split and death. At times the patient reached a condition close to hysterical conversion with feelings of suffocation, trembling and stiffness of the body. Due to this manifest lack of inner psychic transformation the symptoms of conversion served as a

21

release mechanism for excessively strong stimuli and experiences. Their pressure, the lack of “damping” mechanisms, the lack of psychic organization made her defend herself by “rejection of response” (stiffness, immobilization, thoughts of death) as one possible solution, or by violent psychophysical responses (vomiting, accelerated heartbeat, headaches) as another possible solution. Her conversion tendencies, her fear before the coming of fear, were an expression of psychic panic in face of an insufficient capacity for inner psychic transformation, lack of a more serious preparation to carry “psychic loads.” The capacity to handle such loads appears only when there is a clear hierarchization and structuring of the “higher” and the “lower” in oneself. The “higher” is represented by the capacity for empathy, self-control, autonomy and authentism.

5. The patient exhibited a facility in changing from conditions of emotional upheaval, joy and enthusiasm to apathy and pessimism, accompanied by lack of thirst or hunger, headaches and feelings of insecurity. These symptoms can be correlated with her cycloid traits manifested in changeability of her moods: fears, depressions and insecurity alternating with excitement and enthusiasm. Excessive sensitivity, enthusiasm and joy had to be counter-balanced by sadness, depression, and pessimism. Such extreme expenditures of energy caused the opposite symptoms of psychic depletion, mental “shrinking,” energy shut-off, moving away (estrangement). Such reactions result from insufficient transformation of stimuli. W.J. did not have a higher center of control, or a center of hierarchization. Her life was evolving as if on one major plane only. Or one could say that she had only one level of polarization meaning that she was between two poles of her moods fluctuating between high and low, positive and negative, like excitement and depression

6. Excessive concentration on herself and living through unpleasant psychosomatic changes led her to the con-

22

viction that she was being observed all the time and that others saw these changes in her and that they regarded them as pathological. Because of that she had feelings of estrangement. Hence, worries about her features or complexion—fear to look into the mirror, fears of change, fears of being caught by surprise, fear of becoming insane, etc. She always thought she was in worse condition than she actually was. The weakness of hierarchization (inactivity of “higher” dynamisms) with great but one-level sensitivity towards herself and the environment precluded any reflection and change of the feeling of being observed by others. We see in W.J. a lack of a broader, more objective look at herself that normally leads to a broader, more objective and more conscious evaluation of oneself. She lacked perspective in looking at her own symptoms, was unable to interpret them to herself. Her mental activity tied as if to one plane lacked the sense of “multilevelness within oneself” which permits to take a look at oneself from above, i.e. from the position of higher processes such as self-awareness, self-control and others.

7. Signs of actual weakness, amplified by autosuggestion led her to a pathological need of always securing a free path of escape For example, in a cinema or theatre she occupied a seat near the exit; in an uncomfortable social situation she placed herself near the door. Increased excitability, introvertization and weak inner psychic transformation were the basis of a defense by way of “escape” or by way of releases involving little control.

8. The tendency to develop these conditions were innate (forms of her overexcitability, suggestibility, and nuclei of an ahierarchical inner psychic milieu were evident in her from childhood), and were intensified by the transition from a protective psychical atmosphere during childhood and adolescence on one hand, to less attractive environment during her adult life. The condition was aggravated by inappropriate upbringing (she was spoiled by her

23

parents) and her specific history of emotional experiences. Although she possessed these negative symptoms which were unpleasant to herself as well as to others, she was sensitive, individualistic, subtle, talented in some ways, and was very easily influenced in the development of her psychoneurotic condition. She was more susceptible to positive than to negative influences, but she was easily swayed by either. Thus we find a positive correlation between the symptoms of neurosis on one hand, and positive elements of the patient’s personality on the other. We see here distinct nuclei of positive development which had been arrested by lack of understanding on the part of the parents, her husband, and her physicians who treated her as ill and did not see her relatively rich developmental potential (emotional sensitivity, talents, highly altruistic behaviour when the members of her family were in danger).

9. Excessive sensitivity, excessive concentration on oneself, lack of a sufficiently rich syntony with the environment, lack of sufficiently developed hierarchy of values, a failure to develop a disposing and directing center at a high level all point to a lack of strong developmental potential.

10. She periodically expressed very strong interest in others, empathy, and readiness to help others in a deep way.

Nevertheless these relatively good nuclei of positive development did not find correspondingly good conditions in her environment, on the contrary, they were rather negative (she was treated as a hysteric).

In our view, several elements of her personality did not permit a sufficient, positive mobilization of her rich developmental potential, although weak in autonomous factors. Among these we would include her hypersensitivity, a great facility for transposition of psychic experiences into the autonomic nervous system, her lack of development of psychic independence, and a disproportion between excessive sensitivity and in-

24

sufficiently strong sense of self-awareness and self-control. Furthermore, there was a lack of external stimuli which could help promote a certain degree of emotional resilience—all these elements did not permit a sufficient, positive mobilization of her rich but unutilized developmental potential.

From the standpoint of the theory of positive disintegration the stimuli she received were insufficient to mobilize and develop an inner psychic milieu, a hierarchy of aims, a disposing and directing center at a high level, or any interests and talents as well as autopsychotherapeutic dynamisms.

In conclusion let us compare the negative and the positive elements of W. J.’s development:

25

Case 2

S. Mz. was 34 years old. She had a Master’s degree in engineering. She came with complaints of sleeplessness, depression, feelings of estrangement from herself, and a tendency to self-mutilation. She has suffered from these for many years. There were numerous symptoms such as weakening of powers of atten

26

tion and concentration, disturbances in mental work, and weakening of memory. Furthermore, she experienced a rather definite decrease in will power; she could not force herself to work.

The patient was treated with several varieties of tranquillizing drugs. She went through two out-patient insulin therapies. Her condition then improved, but only to deteriorate soon after. An especially important aspect was a depression accompanied by a tendency for escape into the world of fiction. The patient, as she herself said, was in a catastrophic personal situation. However, she did not care for an acceptable standard of living. Every deterioration of her living conditions brought her to a state of “psychic harmonization.” At the same time her reaction, to any stupid or fiat remark was very strong, almost physical. She was always far from the realities of life, living “in clouds.” She stated that she had no “emotional temperature”; she could not love or hate anyone. She liked to create theories of social, moral or philosophical nature.

Her life was difficult since her mother had brain sclerosis. She was professionally capable, but her working conditions became difficult; she was often treated maliciously. She was strongly emotionally attached to a man who died of a serious, incurable disease. This was a destructive experience for her. More recently she could not sleep at all, except after taking Evipan (Hexobarbital). She had feelings of estrangement from herself and thought she was becoming schizophrenic. Yet this was to her a consoling thought. She would have liked to be in a hopeless state. She came hoping to hear confirmation of her pathological condition.

She did not have any negative developmental potential (i.e. no evidence of psychopathy, mental retardation or psychosis); her positive potential was manifested early as an emotional and imaginational overexcitability combined with a predominance of introvertive traits.

General medical and neurological examination:

Thin, somewhat weak constitution, strong trembling of eyelids, slight trembling of hands, light pulse, low blood pressure, ex-

27

cessive and strongly inhibited muscular reflexes, increased and extended red dermographia.

Strong trembling of eyelids, moderate trembling of hands and enhanced muscular reflexes indicate (in the absence of organic changes) an increased psychic overexcitability and also certain degree of disharmony between excitation and inhibition. Such interpretation denotes an introvert type with a tendency to excessive inhibition.

Descriptive diagnosis

Asthenic, schizothymic, introvert, with exceptionally high emotional sensitivity and imagination, weak tension of reality function (i.e. in regard to her external affairs and her work) at a low level, tendency to dwell on things transcendental. Inadequate adaptation to reality, low vitality. The dominating difficult experiences with which her personality could not cope resulted in fatigue and emotional exhaustion, in feelings of emptiness and estrangement from reality and from herself as a real being. Injustice, disappointments, suffering and exhaustion resulted—as is the case with many individuals of this type—in an attitude of “completing the defeat brought by fate and bad luck” through self-mutilation, and an apparent need for experiencing the worst, even death. The disposing and directing center was represented by the tendency towards self-destruction and self-annihilation. We observe here a reversal of the usual hierarchy of values and goals. The supreme “value” and `goal” here becomes death itself; the death instinct takes on the role of the disposing and directing center.

Clinical diagnosis

Psychasthenia with a strong component of depression; possibly a borderline case of schizophrenia.

Justification of diagnosis from the standpoint of the theory of positive disintegration

S. Mz. shows disorder of functions and psychosomatic suffering resulting partly from constitutional characteristics (emot-

28

ional and imaginative overexcitability) which are aggravated by strong and difficult experiences. At the same time we notice a high level of mental sensitivity, a distinct development of moral feelings, and a tendency towards cultivation of exclusive forms of emotional attachment. This last tendency is a natural consequence of her enhanced emotional excitability which is one of the components of her developmental potential. She showed this emotional overexcitability rather early in life. As a child she was stubborn, emotionally independent and in a childish way independent in her thinking. At times she also suffered from anxieties. However, the unfavourable conditions of her life prevented the development of all her psychic resources.

A characteristic feature is the differentiation of reality function into two levels. The lower level (coping with external affairs, her job and everyday living) underwent almost complete atrophy whereas the growth of the higher level was unequal and in part excessive. It was represented by her moral sensitivity and search for philosophical answers to the meaning of her life. Weakening of the instinct of self-preservation was accompanied by the appearance and intensification of the instinct of death and tendency toward self-destruction.

This patient represents a clear instance of multilevel disintegration, even if limited in scope. We are dealing in this case with such strong forms of emotional and imaginational overexcitability and with such distinct introversion that under the impact of grave experiences and also the pressure of complex experiential contents, there appears to take place a not totally conscious uncovering of the basic dynamisms of positive breakdown. There is high tension, frantic search for solutions, realizations of the instinct of partial death, striving for the atrophy of lower level functions, seeking suffering) with an ambivalent mobilization of suicidal tendencies, supersensitive hierarchization of values, transposition of the reality function to a higher level (i.e. into the world of fantasy, imagination and transcendental problems).

The therapy should concentrate upon developmental and creative forces both in the patient’s inner psychic milieu and

29

in her external environment. These forces should be used to increase her interest in life and to promote further mental growth. Despite her depressions and suicidal tendencies she had a high level of enthusiasm which could be awakened by strong authentic agents (e.g. getting involved in valid and important philosophical or social movement, great love or friendship). Such development has to take into account further intensification of creativity; it needs to include a search for existential under-standing, a search for new friendships to be developed with a deeply empathic attitude. It would be absolutely necessary to help her find such friends.

Case 3

S.P. was a priest 26 years old. He came seeking advice regarding feelings of insecurity, scruples and an inability to see what is a sin and what is not. The patient was sensitive and nervous from childhood; he was attracted to the life of prayer, and to understanding and helping others. He entered the seminary since he felt it was his vocation to help others as a priest. For several years he had recurring doubts as to whether he thought and acted properly. He had feelings of inferiority, and was convinced of being worse than others. He did not remember well positive things about himself and his actions except those that had a “shade of sin.” The feeling of his sinfulness often grew out of proportion. If he saw a poor or sick person or was a witness to violence and could not help, he had feelings of guilt and of having failed in his duty. He was very sensitive to the feelings in people and animals. The possibility of causing sorrow to another person made him feel very uneasy. He was in perpetual doubt whether his confessions were good; he kept wondering if he did not omit something. He thought God will judge him severely. He feared professors and examinations. There were no sexual problems.

General medical and neurological examination:

Ascetic look, concentrated face, deep-set eyes, gentle and humble attitude. Pulse rate normal; trembling of eyelids; blood

30

pressure 150/80; red dermographia pronounced and prolonged. High ability to transpose psychical experiences onto the autonomic nervous system exemplified by irregularity of his pulse under emotional stress, sweating, red dermographia, blushing.

Descriptive diagnosis

Individual with a high degree of sensitivity since childhood. He was educated in a cultured milieu in a family with strict moral demands. A contact introvert type (Rorschach). He was meditative, inclined to exaltation, and was striving for the formation of a disposing and directing center at a higher level, tending towards the personality ideal. He was shy and hyper-sensitive, susceptible to moral scruples and states of existential anxiety. His life-experiences developed into a process of multilevel disintegration, with its characteristic dynamisms such as feelings of inferiority, dissatisfaction with himself, feelings of guilt and sinfulness.

Clinical diagnosis

Obsessive psychoneurosis.

Justification of diagnosis from the standpoint of the theory of positive disintegration: