Note: this file is based upon an OCR rendering of the original text and may contain typographical errors. As well, this OCR has auto-spelling correction (the manuscripts have multiple spelling mistakes). When quoting material please consult the original image files of the text to ensure accuracy. I have tried to maintain a good approximation of the original materials.

Note: this file contains all of part one and the first four chapters of part two. Due to the many tables and complex text, OCR did not work well enough to create an HTML file, therefore part two is presented in its entirety as a PDF – see 2.1.13.

MULTILEVELNESS

OF EMOTIONAL AND INSTINCTIVE

FUNCTIONS

TOWARZYSTWO NAUKOWE

KATOLICKIEGO UNIWERSYTETU LUBELSKIEGO

Prace Wydziału Nauk Społecznych

41

Lublin 1996

Kazimierz Dąbrowski

Multilevelness of emotional and instinctive functions.

LUBLIN 1996

TOWARZYSTWO NAUKOWE

KATOLICKIEGO UNIWERSYTETU LUBELSKIEGO

Wydanie publikacji dofinansowane

przez Komitet Badań Naukowych

© Copyright by Eugenia Dąbrowska 1996

ISBN 83-86668-51-2

Wydawnictwo Towarzystwa Naukowego

Katolickiego Uniwersytetu Lubelskiego

ul. Gliniana 21, 20-616 Lublin, tel. (0-81) 525-01-93. 524-31-77, fax 524-31-77

Druk: „Petit” SC, ul. Grenadierów 13, 20-331 Lublin

CONTENTS

Introduction (Czesław Cekiera SDS)——XI

Part 1

THEORY AND DESCRIPTION OF LEVELS OF BEHAVIOR

1. Introduction——3

The Need for a Developmental Paradigm——3

The Need to Discover Emotional Development——5

2. Multilevelness, Disintegration and Developmental Potential——8

The Concept of Multilevelness——8

Positive Disintegration——10

Integration and Disintegration——13

The Concept of Developmental Potential——13

3. Levels and Types of Development——17

Levels of Development through Positive Disintegration——17

Types of Development——20

Hierarchy of Levels as an Evolutionary Scale——23

4. General Characteristics of Developmental Evolution——24

The Role and the Nature of Conflict in Development——24

On the Non-derivability of Multilevel from Unilevel Structure——25

General Trends of Neuropsychological Evolution——26

A Scale of Functions and Level Characteristics——28

5. Dynamisms: the Shapers of Development——30

The Determination of Levels Development by Dynamisms of the Inner Psychic Milieu——30

Level I: Primary Integration——32

Level II: Unilevel Disintegration——33

Level III: Spontaneous Multilevel Disintegration——35

Level IV: Organized (Directed) Multilevel Disintegration——38

Level IV-V: The Borderline of Organized Multilevel Disintegration and Secondary Integration——42

6. The Shaping of Behavior by the Dynamisms of the Inner Psychic Milieu ——44

Observable Behavior versus Hidden Constructs——44

Four Functions: Sexual Behavior, Fear, Laughter, Reality Function——45

Differential Interlevel Diagnosis——64

Developmental Gradients——67

7. Psychic (Nervousness)——71

Forms of Overexcitability——71

Levels of Overexcitability——74

Sensual Overexcitability——75

Psychomotor Overexcitability——75

Emotional Overexcitability——76

Imaginational Overexcitability——77

Intellectual Overexcitability——79

8. Basic Emotional and Instinctive States——79

Excitation——79

Inhibition——81

Suggestibility——82

Pleasure——83

Displeasure——85

Joy——86

Sadness——87

Laughter——88

Crying——88

Anger——89

Fear and Anxiety——91

9. Emotional-Cognitive Functions——92

Reality Functions——92

Success——92

Ideal——93

Justice——94

Immortality——95

Religious Attitude and Experience——96

Esthetic Attitude and Esthetic Experience——98

10. Cognitive Functions——100

Cognition——100

Intuition——102

Criticism——103

Uncertainty——104

Awareness——105

11. Imaginational Functions——107

Reverie (Daydreaming)——107

Magic——108

12. Complex Emotional Functions——110

Enthusiasm——110

Frustration——111

Affective Memory——113

Emotional Ties——114

Solitude——116

Attitude toward Death——117

Suicide——118

13. Self-Oriented Functions——120

Selfishness——120

Self-Preservation——121

Courage——123

Pride and Dignity——124

14. Other-Oriented Functions——

Altruism——126

Sincerity——127

Humility——128

Responsibility——129

15. Social and Biological Functions ——131

Social Behavior——131

Adjustment——132

Inferiority toward Others——134

Rivalry——135

Aggression——136

Sexual Behavior——137

16. Some So-Called Pathological Syndromes Nervousness——138

Psychoneuroses——138

Infantilism——140

Regression——141

17. Disciplines——143

Psychology——143

Psychiatry——145

Education——147

Philosophy——148

Religion——150

Ethics——151

Politics——153

References——155

Part 2

TYPES AND LEVELS OF DEVELOPMENT

Acknowledgments——159

1. Introduction——160

The Beginnings——160

Methods of Data Collecting——161

The Endowment for Development: Psychic Overexcitability——162

Types of Development——164

Levels of Development——164

Manner of Presentation——166

2. Selection of Subjects and Administration of Tests——168

3. Methods——171

Inquiry and Initial Assessment of Development——172

Autobiography——174

Verbal Stimuli——177

Dynamisms——179

Overexcitability——181

Intelligence——182

Neurological Examination——183

4. Developmental Assessment——191

Synthesis——191

Clinical Diagnosis——191

Prognosis——192

Therapy through Diagnosis——192

Social Implications——193

5. Primary Integration——194

Inquiry and Initial Assessment of Development——194

Autobiography——195

Autobiography: Summary and Conclusions——199

Verbal Stimuli——200

Verbal Stimuli: Summary and Conclusions——202

Dynamisms——204

Kinds and Levels of Overexcitability——265

Neurological Examination——206

Developmental Assessment——207

6. Partial Disintegration and Partial Integration——211

Inquiry and Initial Assessment of Development——211

Autobiography——212

Autobiography: Summary and Conclusions——217

Verbal Stimuli——218

Verbal Stimuli: Summary and Conclusions——229

Dynamisms——231

Kinds and Levels of Overexcitability——232

Neurological Examination——234

Developmental Assessment——236

7. Unilevel and Multilevel Disintegration——239

Inquiry and Initial Developmental Assessment——239

Autobiography——241

Autobiography: Summary and Conclusions——252

Verbal Stimuli——253

Verbal Stimuli: Summary and Conclusions——262

Dynamisms——264

Kinds and Levels of Overexcitability——265

Neurological Examination——268

Developmental Assessment——269

8. Unilevel and Multilevel Disintegration Accelerated Development——272

Inquiry and Initial Assessment of Development——272

Autobiography——273

Autobiography: Summary and Conclusions——294

Verbal Stimuli——300

Verbal Stimuli: Summary and Conclusions——305

Dynamisms——307

Kinds and Levels of Overexcitability——309

Neurological Examination——312

Developmental Assessment——313

9. Multilevel Disintegration: Accelerated but Discontinuous Development——317

Inquiry and Initial Assessment of Development——317

Autobiography——319

Autobiography: Summary and Conclusions——338

Verbal Stimuli——340

Verbal Stimuli: Summary and Conclusions——344

Dynamisms——347

Kinds and Levels of Overexcitability——349

Neurological Examination——351

Developmental Assessment——354

10. Multilevel Disintegration, Accelerated Development——357

Inquiry and Initial Assessment of Development——357

Autobiography——359

Autobiography: Summary and Conclusions——378

Verbal Stimuli——380

Verbal Stimuli: Summary and Conclusions——386

Dynamisms——389

Kinds and Levels of Overexcitability——391

Neurological Examination——392

Developmental Assessment——395

11. Organized Multilevel Disintegration, Moving to Secondary Integration——399

Antoine Marie Roger de Saint-Exupéry (1900-1944)——399

Biographical Fragments, Letters, and Excerpts: Summary and Conclusions——422

Kinds and Levels of Overexcitability——428

Developmental Assessment——430

12. Profiles of Development——433

References——436

Index of Subjects——437

Index of Names——445

INTRODUCTION

The work of Prof. Kazimierz Dąbrowski entitled Multilevelness of Emotional and Instinctive Functions is a fruit of long-standing and revealing research carried out by the Professor on the multilevel character of the emotional functions and on the role of emotions in human development. The research was conducted within the framework of a three-year scholarship granted by Canada Council in Ottawa, at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta, at the Department of Psychology, at the Chair of Professor Kazimierz Dąbrowski.

The research was made possible owing to kind support from Prof. Dr. T.M. Nelson, Head of the Department of Psychology at Edmonton University, Alberta, as well as help offered by postgraduate students from the chair of professor K. Dąbrowski. In the works of the group of Prof. Kazimierz Dąbrowski took part the following scholars: Dexter R. Amend, Sister Luz Maria Alvares-Calderon, William Hague, Marlene D. King [Rankel], Michael M. Piechowski, Maurice Taurice Turned, Leondor [Leendert] Mos, Lorne Veudall [Yeudall], and Pat Collins.

Taking a multilevel approach to the issues of emotions and their significant role in the acts of cognition, the work Multilevelness of Emotional and Instinctive Functions introduces us into the sphere of science, as well as orders the discipline which has been little studied so far, and which is highly crucial for the knowledge about man. Accordingly, the work lay a direction for methodological reflection and scientific procedure in the humanities. All this amounts to the fact that the work is ranked exceptionally high within the system of contemporary knowledge. It is a topical work, especially now at the time when aberrant, or even pathological behaviors abound, characterized by “moral callousness,” atrophy of higher emotions, syntony and empathy, by aggressive and terrorist attitudes.

The book makes up a special compendium of the humanistic knowledge on the development of emotions in relation with other dynamisms and functions of personality. Therefore it corresponds to a social and individual demand for a systematic study of the theory of the development of emotions. It should be stressed that the hitherto research has promoted rather the cognitive and intellectual theories of the development of the individual, and neglected the sphere of emotions in the forming of a mature personality.

The fact that prof. Kazimierz Dąbrowski took up emotions and studied their role in the processes of personality development is a pioneering achievement. Many contemporary authorities of contemporary science such as: Abraham Maslow, J. Aronson, H. Quellet, G.R. Dr. Grace, G. Borofsky, K. Jankowski, J. Pieter, P. Joshi, T. Nelson, M. Grzywacz-Kaczynska, O.H. Mowrer, and T. Weckowicz, who spoke about Professor’s work, acknowledge its pioneering role. Numerous comments from patients who turned to the Professor for help as well as passages from His Theory of the Development of emotions pinpoint that there is a social demand for Kazimierz Dąbrowski’s books in general, and in particular for this publication dealing with the development of emotions: Multilevelness or Emotional and Personality Functions.

K. Dąbrowski conducted his scientific and clinical activity in Poland, France, Canada, the United States, Portugal, Switzerland and in many other countries. Some of his works are well-known at home and abroad, but as a whole they were known neither to the Polish nor foreign reader. The present work, which comes to the reader’s hands, is his least known book.

I met Professor Kazimierz Dąbrowski for the first time during my studies at the Catholic University in Lublin in 1958. His lecturers on the conception of mental health, disease, pathology of the person’s development aroused vivid interest among students. Animated discussions about his classes impressed greatly not only students, but involved their participants in the current problems concerning some aspects of social life turned pathological.

The book whose content is the development of affections and emotions grasps crucial aspects and dimensions of the development of personality, things which have so far been presented by the textbooks of developmental psychology only from one point of view, which have been treated with significant simplifications. This publication may give momentum and bring forward suggestions for a new research on the role and function of emotions in the development of a mature personality. Multilevelness, types of development and the traits of development have been analyzed here.

In chapter VI the reader will find a description of the observed emotional behaviors in such dimensions as reality function, diagnosis of the differentiated interlevel behaviors as well as various degrees of the differentiation and hierarchization of emotional values which are not indifferent for the individual. The author describes the states of reflection, inhibitions, syntony and empathy. He states, among other things, that the latter dynamism is the most powerful with prominent authors.

Chapters VII-IX make up very interesting psychological analyses of emotions. The reader will find in them the description and psychical analysis of overexcitability (nervousness) and its diverse forms: a further part presents an analysis of the basic emotional states. Chapter IX discusses the emotional-cognitive functions in the aspect of the reality function, success, ideal, justice, and religious attitudes. The cognitive functions have been described in chapter X. The problem of emotional complexes and states from the borderline of pathology and norm, as well as other emotional states are the subject matter of chapters XII-XV. In chapters XIV and XV the author conducts thorough analyses of such emotions, today barely discussed in professional textbooks, as altruism, sincerity, humility, and responsibility.

The next chapter XVII displays the levels of development in the aspect of various scientific disciplines such as: psychiatry, philosophy, religion, ethics, and political sciences. We should in vain seek the problems discussed in this chapter in other works treating of emotions. Therefore this chapter is exceptionally valuable in the book.

The issuing of the book may help us to draw psychological, pedagogic and therapeutic conclusions within the sphere of forming emotions and feelings, and not only their inhibition or containment. The readers of the book may consist of a vast group of the youth, students of psychology, education, and medicine.

The book may serve professionals, psychologists, educators, priests, and the clergy as an aid in the forming of emotions. It may serve anybody who wishes to develop their own personality toward the highest individual and social ideal.

The Multilevelness of Emotional and Personality Functions is an exceptional item at the publishing market. We should wish the patient and careful reader of the book that he have some profound reflections and rich experiences, which in turn will lead to the forming of emotions and a harmonious personality. All those interested in the development of emotions should be wished courage to reach the fifth level of development, where dominates a full awareness of responsibility for the higher moral values; even if we are to lay down our lives to realize those values.

Translated by Jan Klos

CZESŁAW CEKIERA SDS

MULTILEVELNESS OF EMOTIONAL AND INSTINCTIVE FUNCTIONS

Part 1

THEORY AND DESCRIPTION OF LEVELS OF BEHAVIOR

Kazimierz Dąbrowski, M.D., Ph.D.

1

INTRODUCTION

THE NEED FOR A DEVELOPMENTAL PARADIGM

In the last two decades the psychology of human development underwent an “explosion of knowledge” (Mussen, 1970, p. vii). Curiously, however, the concept of development as an approach to the study of human behavior does not appear on the official map of psychological systems (Marx and Hillix, 1963 and 1973) nor do the names of Gesell, Piaget, and Werner appear on the pages of a recent textbook covering the history of modern psychology (Schultz, 1969). Nevertheless, this lack of official theoretical status has not hindered the study of development as a phenomenon in its own right.

Development has many aspects. There is physical growth and physical maturation. There is motor and language development. There is social development which leads to the role and position in society assumed in adulthood. There is intellectual development and learning which may lead to the appearance of individual cognitive style. There is psychosexual development and emotional development, the two often not distinguished at all. The development ascendance is followed by decline in consequence of disease, old age deterioration of the body, loss of social function, senility and death. Not all aspects of development, and only several have been mentioned, are studied with equal vigor, while the study of some has not yet actually been attempted.

On the official map of developmental psychology (Mussen, Langer, and Covington, 1969; Mussen, 1970) we note a prominent presence of cognitive. studies and an equally prominent absence of studies on affect. That means that emotional development does not appear on the map of developmental psychology. But unlike development in general, and cognitive and moral development in particular, emotional development is not even recognized as a phenomenon in its own right.

4 Theory and Description of Levels of Behavior

Indeed, it appears that emotional development is a blank space in developmental theory and research.

It is possible that the reason for this lies in a commonly held conception of emotions as something ephemeral, elusive, ill-defined and not researchable by other than clinical methods. But this is no longer so. The phenomenon of emotion is recognized and is the subject of a host of studies and reviews (Davitz, 1969, Arnold, 1971, Izard, 1971, Strongman, 1972, Leventhal, 1974). Feelings have been shown to be very precise phenomena of dynamic communication, perhaps more precise, than sensory perception (Clynes, 1970). But except for unsystematic psychoanalytic approaches dealing with neurotic and sexual conflicts a systematic approach to emotional development has not yet appeared.

The fact that the developmental approach in psychology is not recognized as a system of thought, or paradigm, is intriguing. The roots of this appear to be historical. For a long time development was seen as a function of age, that is as a function of time. Time, therefore, was just another parameter in the study of human behavior. Within such an approach development could not present anything distinctive.

The situation is different in biology where development for over 150 years was known as a complex process of differentiation and sequences of changes in structural and functional organization of living organisms. The development of the embryo from one cell into a complex multi-cellular organism goes through many stages characterized by different morphology and different biochemistry. In consequence, the structures and the functions of an organism at different stages of development can be so different as to be unrecognizable. Compare, for example, the tadpole and the frog, the larva and the butterfly, the human embryo in the first few weeks and the newborn infant. Similar differences can be found in the complex life cycles of fungi, mosses, ferns or higher plants. Or, take the extreme example of a virus which after infecting a cell vanishes so entirely as an entity that this stage of its development has been called the “eclipse” (Stent, 1963). In some instances the different stages of ontogenesis of a single organism were at first described as different species.

The point of the above biological invocation is first, that it is necessary to follow the sequence of developmental transformations if the phenomena of life, including human behavior, are to be understood; second, that the different stages of development can be so dissimilar that without knowing their succession they could appear unrelated; third, that there must be an underlying structure which secures the continuity and regularity of development. At the biological level this structure is the genetic material and its function is storage of information. What would correspond to that structure at the psychological level we do not know. We know, however, that the awareness of one’s identity persists through wakefulness and sleep, through grave emotional crises, or through periods of amnesia.

The application of developmental biological knowledge to human psychological development was attempted by Gesell (1946), Piaget (1967, 1967a, 1970) and

Introduction 5

Werner (1948, 1957). Their attempts focused on identifying those general principles of development established in the biological realm which could also apply to the psychological. Closely examined, those principles are essentially descriptive. They do not explain developmental phenomena because they do not point to specific processes which would account for a given transformation.

This, perhaps, is the reason why the developmental orientation in psychology, in spite of its vast membership and explosive output, has not risen to the rank of a system of thought. The function of a system is to provide an “inclusive framework which serves as a general theory of the subject” (Marx and Hillix, 1963). The function of a general theory is not only to describe and identify specific phenomena and relationships between them but also to provide means of explication (Piechowski, in press).

In this sense the developmental theories of Piaget, Werner, and the psychoanalytic theory are descriptive. They describe the course of development, identify the distinctive features of its different stages, correlate them with age, establish relationships between different structures and functions, but do not tell what specific, identifiable, unitary factors can account for the transition from one stage to another. The psychological analogs of genes and molecules are yet to be discovered.

The attempt to identify the “molecules” of psychological development is best exemplified by the work of Piaget (1970). His conceptualization of internal structures and functions which cannot be observed but which can be discerned in a child’s method of handling cognitive tasks provides us with the psychological analogs of biological structures and functions.

Nevertheless, the analogs of the genes are yet to appear.

THE NEED TO DISCOVER EMOTIONAL DEVELOPMENT

If the first revolution in American psychology was behaviorism, the second appears to be “a kind of cognitive functionalism” (White, 1970). The study of development and the theories of development are now focused on problems of cognitive development while those of emotional development lie fallow.

The reason for this is hard to find if one is aware of the power of emotions in human experience, but if one looks at the development of the science of human behavior, it is not so hard to understand the reasons for leaving emotional development out of the picture. For several decades learning had been one of the central issues in American psychology. Consequently, the study of cognitive development finds, in a certain way, a prepared ground. On the contrary, a systematic psychology of the emotions is a recent occurrence, too young and too limited theoretically and methodologically to have prepared the ground for a study of emotional development.

Thus, a third revolution is needed. Our understanding of human behavior and human development cannot be complete without the study of emotional develop-

6 Theory and Description of Levels of Behavior

ment. Not only does human life lose meaning if the emotional component is taken away, but a general theory of human development is not possible if it does not include emotional factors. But we have to go even farther than that. Emotional factors, more than the acquisition of symbolic language (Pribram, 1971), are significant in the process by which man becomes human. Therefore, they not only have to be included but must be given a position of primary importance.

The various levels and complexities of human experience cannot even be approached without considering the emotions which give rise to them. Stripped of affect, human relationships become meaningless, albeit theoretically tractable (e.g. Heider, 1958). The age-old problems of universality and objectivity of human values and value judgments cannot be solved if the emotions which generated the hierarchy of values are not brought into the picture (Dąbrowski and Piechowski, 1970); similarly, when we try to penetrate the mystery of creativity and religious experience, both associated with rich affectivity, we cannot comprehend them without taking into account emotional development.

We need a general theory of human development but one which would include and account not only for cognitive but for emotional development as well, and let us hasten to add, a theory where emotional factors are not considered merely as unruly subordinates of reason but can acquire the dominant role of shapers of development. This last requirement, namely to bring emotional factors into the forefront of developmental dynamics, is not arbitrary, although it may appear emotional, but stems from a comprehensive analysis of human development.

When one studies the life histories of writers, composers, artists, scientists, one is struck by the fact that from early childhood they manifest an enhanced mode of reacting to the world around them. Furthermore, their enhanced reactivity is coupled with intensified experiencing in cognitive, imaginational, and emotional areas. One observes a similar pattern in gifted and creative children and youth (Dąbrowski, 1972). In tracing the development of such individuals it becomes quite clear that in those cases where development reaches toward universal human values, i.e. values which persist across epochs and cultures, emotional factors play a dominant role. They appear as internal conflicts, striving through anxieties and depressions for true empathy and genuine concern for others, striving for unique and exclusive bonds of love and friendship, desperate search for the meaning of human existence, or a desperate search for God not as an abstraction or institutionalized father figure, but as a personally felt living presence.

The thesis offered here is the following. The key to the understanding of complex phenomena of human behavior lies in the developmental approach as a system of thought. Just as the theory of evolution reoriented biological thinking from description of isolated phenomena as finished and unchangeable forms to viewing them as a progression of evolving patterns, so a general theory of human development may reorient psychological thinking to a view of human behavior as a progression of differently organized behavioral patterns interweaving hereditary, environmental, and conscious, self-determining factors. Analogous to the

Introduction 7

theory of evolution, a general theory of development could thus become the integrating paradigm for the numerous, disparate, and seemingly unrelated fields of psychology.

We can summarize the foregoing discussion by saying that in spite of the wide front of developmental research a general theory of development which would rise to the rank of a conceptually distinct system of thought in psychology has not yet emerged. The closest to such a general theory are the theories of cognitive development. In our view a general theory of human development must also include emotional development because emotional factors are crucial in shaping the transition from human animal to a human being.

Available theories of development appear bound to an ontogenetic approach. It is our contention that a general theory must look at development as a more general sequence of evolving patterns of organization of behavior. This leads to a discovery of developmental sequences which may occur in some ontogenetic paths but be absent from others. The comparison of these paths will then lead to a more extended overall picture of development that can occur but does not always occur.

The theory of development to be presented here rests on an evolutionary rather than ontogenetic conception of human development. Its central concept is that of multilevelness.

2.

MULTILEVELNESS, DISINTEGRATION AND DEVELOPMENTAL POTENTIAL

THE CONCEPT OF MULTILEVELNESS

In 1884 John Hughlings Jackson delivered three lectures on the Evolution and Dissolution of the Nervous System. In these lectures he presented the idea that progressive impairment of neurological activity, such as observed in epileptic seizure, descends step by step down the evolutionary strata of the nervous system.

The evolution of the nervous system is a particularly striking example of development of new structures and associated functions. This development is hierarchical because the organization of the nervous system is hierarchical. The relationships between levels of this hierarchy are very intricate but here we want only to point out one general feature which was particularly significant to Jackson’s line of thought, namely, that higher levels control lower levels through inhibition. Thus, when alcohol, extreme fatigue, or epileptic seizure dim consciousness and voluntary activity, the highest level of neurological functioning is impaired, or “dissolved.” The next lower level is now functionally the highest and the controlling one. But it is more automatic. If, in turn, this level is “dissolved,” the organism’s functioning descends again to the next lower and even more automatic level.

Jackson said that automatic actions can be automatic because they are independent of other actions. In consequence, they have simple organization, even though they may be quite elaborate. Automatic action has to run its course, it can be stopped but it cannot change pattern or sequence. Functional complexity, on the other hand, requires intricate and mutually responsive mechanisms. With this in mind Jackson formulated three laws of evolution of the nervous system:

(1) Evolution is a passage from the most to the least organized; “the progress is from centers comparatively well organized at birth to those, the highest centers, which are continually organizing through life.”

Multilevelness, Disintegration and Developmental potential 9

(2) Evolution is a passage from the most simple to the most complex.

(3) Evolution is a passage from the most automatic to the most voluntary. The essence of Jacksonian thought is that the highest levels of nervous activity are the most complex and the least automatic. It is, however, hard to accept his view that they are also “least organized.” Rather, one may say that they are more flexible and because of their complexity, allow a multiplicity of operations (Dąbrowski, 1964).

The significance of Jackson’s theoretical contribution lies in associating a hierarchy of levels of functioning with evolution and suggesting its general trends. Jackson represents a multilevel and evolutionary approach to development.

Such a concept of multilevelness differs from that of Piaget. For Piaget conceptualizes development in terms of stages. Each stage represents a more complex and more efficient level of organization produced in the course of ontogenetic development. It is the process of development which produces the different levels in stage wise orderly succession. Piaget’s approach is ontogenetic, while Jackson’s approach is evolutionary (but not necessarily phylogenetic).

The studies of McGraw (1943) provide a link between these two approaches. The control of movements and reflexes develops during infancy and childhood through successive phases. The early phases are automatic, the later ones deliberate and voluntary. The transition from the early to the late ones requires inhibition, analogous to Jacksonian inhibition of lower, more automatic levels by higher, more voluntary levels. At the time of gaining voluntary control, for instance of grasping, the early automatic control is inhibited with the result that the baby’s ability to support his weight is comparatively high up to the age of 40 days, then is gradually lost, and is not regained at the same level of proficiency until the age of 5. But by then it is voluntary and deliberate. This demonstrates how a level higher in the evolution of functions is acquired in the course of ontogenesis. McGraw’s approach is both ontogenetic and evolutionary.

In the theory of positive disintegration (Dąbrowski, 1949, 1964) development is a function of the level of organization. We have argued earlier that the most significant aspect of human development is emotional development but we now have to point out that it has different character than neuromuscular or cognitive development. There is no, as yet, discernible ontogenetic pattern of stages of emotional growth. Children gradually develop their ability to recognize emotions as a function of age, while adults appear to gradually lose it (Dimitrovsky, 1962). The solution to this contradiction lies in approaching emotional development as a nonontogenetic evolutionary pattern of individual growth. This means that the level of emotional functioning is not produced automatically in the course of ontogenesis but evolves as a function of other conditions, which we shall examine later. Thus a high level of cognitive functioning in no way guarantees a high level of emotional functioning. The reverse may not be true.

10. Theory and Description of Levels of Behavior

Making multilevelness the central concept in the approach to development means that we have to apply it to every phenomenon under scrutiny. It means that we are using a new key, or paradigm, with which to approach human behavior and its development. It now becomes less meaningful to consider, for instance, aggression, inferiority, empathy, or sexual behavior as unitary phenomena, but it becomes more meaningful to examine different levels of these behaviors. Through this approach we may discover that there is less difference between the phenomenon of love and the phenomenon of aggression at the lowest level of development than there is between the lowest and the highest level of love, or the lowest and the highest level of aggression (at which point there is no aggression but instead empathy for the opponent).

The enormous amount of differentiation occurring across levels will show us that, in general, at the lowest level of development different behaviors have a fairly simple underlying structure. We call it primary integration. With the progress of development toward higher levels the process of differentiation becomes so extensive that the differences between levels are greater and more significant than differences between particular functions (i.e. behaviors).

The concept of multilevelness is thus the starting point for the analysis of all forms of behavior and their development. It represents the new “system of thought” which we see as necessary to represent the developmental approach on the official map of psychology and the clinical sciences as well. Nevertheless, this conceptual orientation, however fruitful for the analysis of behavior and development, requires something more which would account for the fact that not all individuals, in fact very few, reach the highest level of development. If it is not the length of time needed to complete the ‘cycle of individual evolution’ through many levels, and it is not, it must be something else. At this point a new concept is needed.

In order to account for differences in the extent of development we introduce the concept of the developmental potential (Dąbrowski, 1970, Piechowski, 1974). The developmental potential is the original endowment which determines what level of development a person may reach if the physical and environmental conditions are optimal. The concept of developmental potential is a necessary one. In a later section we shall describe the components and manifestations of the developmental potential and its interaction with three basic sets of factors affecting development.

POSITIVE DISINTEGRATION

Jackson (1884) did not specify what the processes of evolution are and by what mechanisms a transformation takes place from a lower to a higher level, from simple to complex, from automatic and unconscious to voluntary and conscious. Many mechanisms, viewed by him as “dissolution,” play a key role in evolution. We call them processes of positive disintegration.

Multilevelness, Disintegration and Developmental potential 11

There is no reason to believe, as Jackson did, that “dissolution” starts from higher and more recently evolved functions and proceeds downward to simple automatic ones. The course of life of prominent individuals, highly creative persons, and many psychoneurotics, reveals a disintegration, or even atrophy, of simple automatic functions, while the higher and more complex functions retrain fully intact. A prolonged hunger strike or self-immolation by fire as a moral protest are proof of complete control over self-preservation, hunger and pain. A recovery from mental illness—a form of “dissolution” to Jackson—can result not in a return to a previous supposedly “normal” condition but to a higher level of mental functioning and creative output (Dąbrowski, 1964). Obviously a new and higher level of functioning could not exist in a dissolved state but must have been intact, although hidden. Or, at least, whatever gives rise to it, must have been intact.

In the process of individual evolution the factor of conflict with one’s milieu and with oneself plays a decisive role in inhibiting primitive impulses. Internal conflict becomes thus a controlling factor. It is also more complex than the impulse it inhibits. Thus the impulse represents a higher level of functioning according to the rules of hierarchical organization laid out in the discussion of multilevelness.

Reflection, hesitation, and inhibition are less automatic than an immediate response to stimuli. They represent a reaction to stimuli which cannot be derived from the stimulus the way a tropism response may be derived, as for instance, in the case of positive phototropism when movement toward light appears automatically with the shining of light.

The less automatic but more voluntary responses are in conflict with the old conditions and modes of functioning. Such conflict is a necessary prelude to the gradual process of adaptation to new external and internal conditions. This results in a disequilibrium which allows the emergence and organization of new levels of control, higher than those of the previous stable period. Thus the instability, and partial, or even complete, disorganization of behavior, is necessary in the process of development from a lower to a higher level of mental functioning. Yet this does not mean that development occurs inevitably.

This view of development as a process of positive disintegration is based on several decades of clinical and psychological study of children, adolescents, and adults, talented and creative as well as retarded and psychopathic (Dąbrowski, 1949, 1964, 1967, 1970, 1972). Gradually it became apparent that within each group the individuals functioned at strikingly different levels, and that these levels had certain distinguishing characteristics. But what was most striking was the realization that those with, as Jackson would put it, partly or completely “dissolved” areas of functioning (creative psychoneurotics, some psychotics) were actually undergoing a process of transformation and reorganization in their internal psychological makeup,. And it was not so much their intellectual but their emotional structure which was being demolished. Amidst the debris a new one would emerge, often not precipitously but slowly and painfully.

12 Theory and Description of Levels of Behavior

This process was called positive disintegration to stress the particular nature of its developmental direction (Dąbrowski, 1949). While Jackson looking at the impaired functions of injured, intoxicated, or epileptic individuals considered only the negative aspect of functional disintegration, the theory of positive disintegration introduces the positive aspect of disintegration as a general developmental principle.

General principles, however, are not very useful if they do not spell out specific factors with which to measure their operation. Thus, for instance, we find in Piaget a mention of lack of equilibrium as a necessary aspect of development (Piaget, 1967b, p. 104). Development, according to him, proceeds through the inclusion of newly encountered aspects of reality (assimilation) and adjustment of available modes of functioning to concrete situations (accommodation). The interplay of these two processes, more and more active as development goes on, is called equilibration. Disequilibrium arises when these two processes are not balanced. Equilibration serves the organism to become more integrated and at the same time more adapted to objective reality. Nothing more is given to make possible an empirical grasp of this general principle. In Piaget’s opinion the interplay of assimilation and accommodation explains development, but for us it is only a descriptive and uncomfortably general principle.

One could review and compare the contrasting features of equilibration and of positive disintegration. But then, we would be arguing the merits and uses of different descriptive principles, similar to Werner’s discontinuity, sequentially, and differentiation.

It is not enough, therefore, to say that positive disintegration, or equilibration, or differentiation, is the process by which individual development may proceed from one level of functioning to the next. One must specify the factors involved and offer means of identifying them. One must, further, be able to show logical connections between different sets of factors. When these conditions are satisfied, a general theory can begin to emerge.

The description and analysis of the wide range of phenomena of disintegration is presented in detail elsewhere (Dąbrowski, 1937, 1967). They are discussed in relation to different types of disintegration, and in relation to certain periods of life, e.g. adolescence or climacteric, and grave events which are particularly stressful and disintegrative. Such phenomena of disintegration are triggered by events in the course of life and changing conditions of the maturational phases of the fife cycle. These events alone cannot account for the great individual differences in how they are experienced and handled. Even less can they be involved to account for those instances where a person deliberately seeks frustration and stressful conditions so that he would not stagnate in his development. Such development, propelled as it were, from within, is a function of strong developmental potential, and is not bound or determined by the phases of the life cycle.

Multilevelness, Disintegration and Developmental potential 13

INTEGRATION AND DISINTEGRATION

Earlier we introduced multilevelness as the central concept of a developmental approach to the study of human behavior. We said that the change from a lower to a higher level of development requires major restructuring of the individual’s psychological makeup. This process was called positive disintegration.

The next step is to uncover how the different developmental levels are related to each other. We shall speak of levels of integration and disintegration.

That type of individual development which follows the maturational stages of the life cycle without any profound psychological transformation, which for us means no change in the emotional structure, we conceptualize as an integration. In such life history an individual follows the path of environmental adaptation. He learns, works, and fits in, but he does not suffer mental breakdown or experience inner conflicts, hierarchization of values and ecstasy. In contrast, when in a life history such phenomena do take place we have disintegration.1

There are many factors involved in development. Our concern here is with the intrapsychic factors which shape development and the expression of behavior. The intrapsychic factors of positive disintegration are called dynamisms. The analysis of these dynamisms and their relative strength allows one to decide whether a given process of disintegration is positive or negative without having to await its outcome.

The levels of integration and disintegration constitute a hierarchy. At the bottom we have primary integration, then three levels of disintegration (one of unilevel, two of multilevel) and finally secondary integration.

The concept of development through positive disintegration means that development occurs when there is movement (i.e. restructuring) at least from primary integration to the first level of disintegration. Development is more extensive if it proceeds through several levels of positive disintegration. Development is most extensive when it reaches secondary integration. This is extremely rare, nevertheless not entirely beyond empirical reach.

THE CONCEPT OF DEVELOPMENTAL POTENTIAL

Developmental potential is the original endowment which determines what level of development a person may reach under ideal conditions.

_____________________

1 Disintegration may be positive or negative. Development is associated with positive disintegration, while chronic disintegration of mental functions is associated with negative disintegration. In is often objected that one cannot decide, prior to the outcome, whether the actual process witnessed is positive or negative. This is not so. There are many identifiable factors involved in the process of positive disintegration. Their presence and level of activity can be assessed at any time and on this basis a very clear picture can be drawn. This is reported in detail in Part 2.

14 Theory and Description of Levels of Behavior

Developmental potential describes the relationships between individual development and three sets of factors which control development (Dąbrowski, 1970). The first set of factors embodies the genes and the permanent psychical changes in the organism’s constitution which may occur during pregnancy, birth, or soon after. For the sake of simplicity we consider only the changes in the physical makeup of the organism. The first factor thus represents innate constitutional characteristics and potentialities of the organism.

The second set of factors represents all the social environmental influences which come from other persons individually or as group pressures. One could venture to say, for example, that the theories of H. S. Sullivan and A. Adler are an elaboration of the role of the second factor in individual development.

The third set of factors represents those autonomous processes which a person brings into his development, such as inner conflict, self-awareness, choice and decision in relation to personal growth, conscious inner psychic transformation, subject-object in oneself. When the autonomous factors emerge, self-determination becomes possible, but not before. This means that an individual can transcend, at least to some degree, the sets imposed on him by his constitution and by the maturational stages of the life cycle.

The developmental potential does not necessarily include a measure of each one of these sets of factors. It can be limited to the first factor alone, or to the first and the second (Piechowski, 1974).

Piaget (1967b, p. 103) also mentions three factors of development, heredity, physical environment, social environment, and adds a fourth, equilibration. The first two of Piaget’s factors correspond to our first factor. But equilibration cannot legitimately be considered a factor in development because just like the time variable (Wohlwill, 1970) it cannot be separated from the process of development itself. One would be making the same logical error were one to consider positive disintegration a developmental factor. Positive disintegration is the process of development. Thus the difference between Piaget and the theory of positive disintegration lies primarily in the inclusion of most psychoneuroses and autonomous factors in development.

When the developmental potential is limited to the first factor we are dealing with a psychopathic or sociopathic individual indifferent to social opinion and social influence, pursuing only his own totally egocentric goals. Such individuals are incapable of reflection on their actions. Their life is a function of externals. This would correspond to Kohlberg’s (1963) stages 1 and 2. For instance when Jimmy Hoffa described to an audience the depersonalization he suffered in prison he could only describe it in terms of being deprived of the choice of haircut, clothing and unlimited use of his money.

The developmental potential can be limited to the first and the second factors only. In that case we are dealing with individuals who throughout their life remain in the grip of social opinion and their own psychological typology (e.g. social climbers, fame seekers, those who say “I was born that way” or “I am the product

Multilevelness, Disintegration and Developmental potential 15

of my past” and do not conceive of changing). External influences from groups or individuals shape their behavior but not necessarily in a stable fashion. Changing influences shift the patterns of behavior or can deprive it of any pattern altogether. Autonomous developmental factors do not appear, and if they do only briefly, they do not take hold.

The developmental potential may have its full complement of all three sets of factors. In that case the individual consciously struggles to overcome his social indoctrination and constitutional typology (e.g. a strongly introverted person works to reduce his tendency to withdraw by seeking contacts with others in a more frequent and satisfying fashion). Such a person becomes aware of his own development and his own autonomous hierarchy of values. He becomes more and more inner-directed.

There is thus an important difference between the first two factors of development and the third. The first two factors allow only for external motivation, while the third is a factor of internal motivation in behavior and development. This is another example where a question of determinants of behavior cannot be properly settled outside the context of development. Aggressiveness, enterprise, and leadership of “self-made” men may often appear to spring from an internal locus of control but more closely examined often show no evidence of autonomous developmental dynamisms. Such individuals may be driven by a great deal of energy but their motives and goals are geared to external norms of success.

The developmental potential may be particularly strong when in addition to the three components there are special talents and particular strength of self-awareness and self-determination, such as manifested in great saints and leaders of mankind. Here development is characterized by great intensity and often severe crises. It is accelerated and universal, meaning that it encompasses the whole personality structure and goes in the direction of high human values and ideals which hold across time and across cultures.

The above description of the developmental potential and its breakdown into three components does not allow one to measure it independently of the context of development. So far we have considered the three factors of development as general sets of conditions which allow only to distinguish an externally from an internally controlled type of development. We need now to identify specific factors whose presence is a condition of development through positive disintegration and whose absence would limit it to primary integration.

In the Introduction we discussed the significance of emotional development. It was mentioned that creative and gifted individuals react and experience in an intensified manner, and that this particular characteristic can be observed in intellectual, imaginational and emotional areas. We now add the psychomotor and the sensual as well. The enhanced mode of reacting in these five areas was called psychic overexcitability (Dąbrowski, 1938 and 1959).

The three forms of overexcitability mentioned first are always associated with accelerated and universal development, that is development in which autonomous

16 Theory and Description of Levels of Behavior

factors are particularly strong (Dąbrowski, 1970). The psychomotor and the sensual forms of overexcitability may enhance such development by giving it more energy and more numerous areas of conflict. However, the psychomotor and sensual overexcitability by themselves alone do not contribute to the autonomous factor. In the case when intellectual, imaginational and emotional overexcitability are weak, or completely absent, development remains under strong, if not total, external control.

The five forms of overexcitability are the constitutional traits which make it possible to assess the strength of the developmental potential independently of the context of development (Piechowski, in press). They can be detected in small children, already at the age of 2-3 (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 8-9). These five forms are described in a different section.

Developmental potential is strongest if all, or almost all forms of overexcitability are present. The three forms, intellectual, imaginational, and emotional, are essential if a high level of development is to be reached. The highest level of development is possible only if the emotional form is the strongest, or at least no less strong than the other forms. Great strength of the psychomotor and the sensual forms limits development to the lowest levels only.

The five forms of overexcitability undergo extensive differentiation in the course of development. One of its products are developmental dynamisms, i.e. the intrapsychic factors which shape and direct development. Emotional and imaginational overexcitability, in cooperation with the intellectual play the most significant role in their formations.

A more precise definition and resolution of the relationships between the three sets of factors and the five forms of overexcitability awaits future analysis.

The developmental potential is a conceptually necessary structure. When the human organism begins to grow and interact with its environment, this structure responds to the three groups of factors determining the course of development. If the developmental potential is limited then development is also limited although there might be no limitations on the external conditions to be the most favorable to nourish even the richest endowment. When developmental potential is present in its full complement then multilevel development becomes possible, i.e. development in which many different levels of experience become active.

Developmental potential may be negative. When enhanced psychomotor or sensual overexcitability is combined with strong ambition, tendencies toward showing off, lying, and cheating, then it constitutes a nucleus of psychopathy and characteropathy (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 11).

3

LEVELS AND TYPES OF DEVELOPMENT

LEVELS OF DEVELOPMENT THROUGH POSITIVE DISINTEGRATION

Even though the emergence of new structures and constellations of functions gives it a discontinuous pattern (Werner, 1957), development is a continuous process. The levels of development through positive disintegration are holistic conceptualizations serving to identify the types of processes involved.

The concept of level means here a characteristic constellation of developmental factors at work. These factors are the intrapsychic dynamisms to be described in Chapter 5.

A level is a distinct identifiable developmental structure. It is not a temporal sequence, which makes it distinct from a stage. Thus when we use the expression “a level is attained,” it means that the structure of a lower level is replaced by the structure of a higher one. Here again, the use of the expression, “transition from one level to another,” is colloquially convenient but inaccurate. In the process of development the structures of two or even three contiguous levels may exist side by side, although it must be understood that they exist in conflict. The conflict is resolved when one of the structures is eliminated, or at least comes under complete control of another structure.

Development does not occur at an even pace. There are periods of great intensity and disequilibrium (psychoneuroses, depressions, creative process), and there are periods of equilibrium. Development achieves a plateau, and this may occur at any level or “between” levels, when the developmental factors are active in shaping behavior but are not active in carrying out further transformation and restructuring. This may denote partial integration. But the more development is advanced, i.e. the higher level it reaches, the less possible it is for it to

18 Theory and Description of Levels of Behavior

slacken off and cease to carry on the process of psychic transformation. This is one reason why such advanced development was called accelerated (Dąbrowski, 1970). Here acceleration does not denote a rate of change toward completion but rather the greatest extent and depth of the transformation of personality structure.

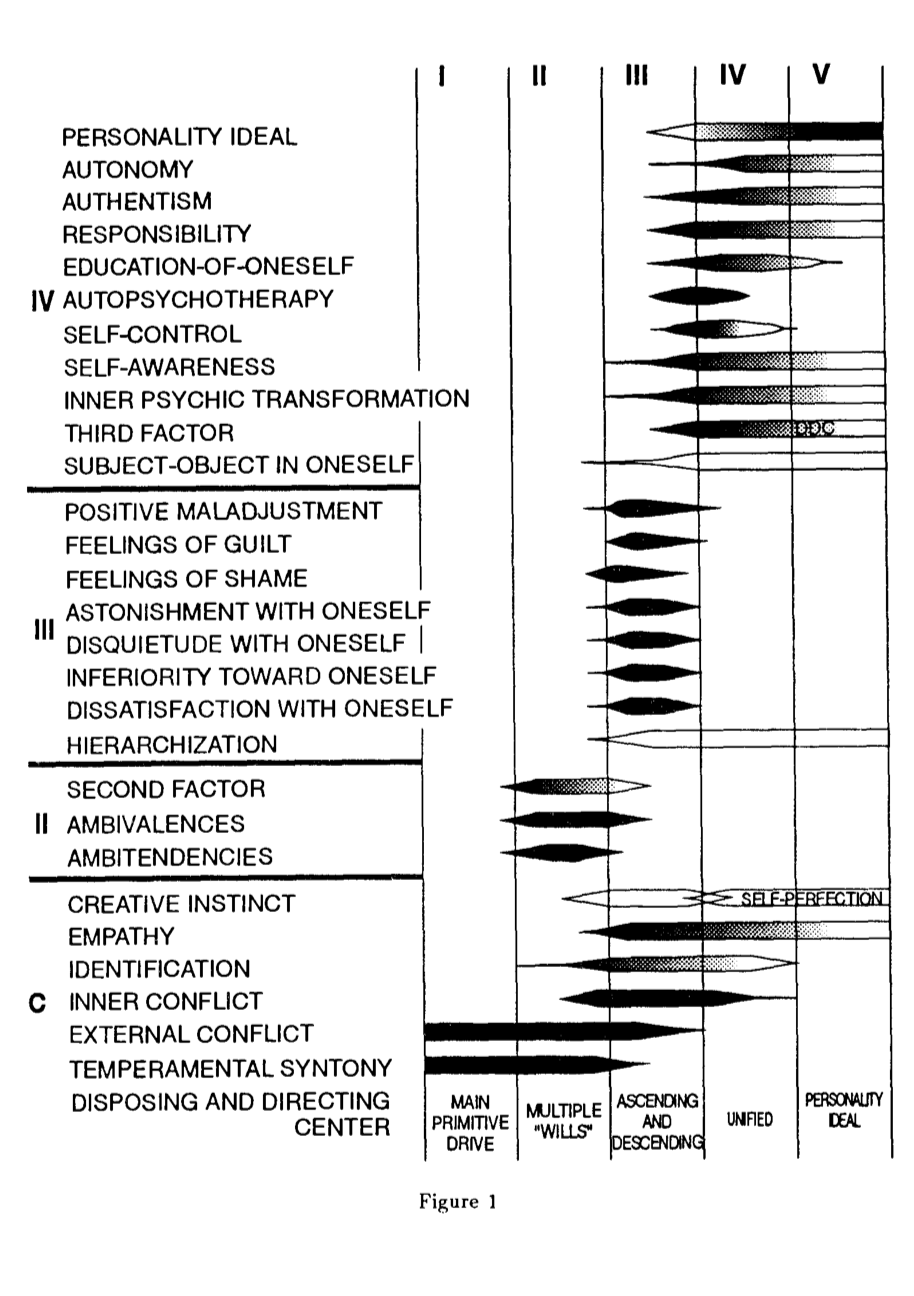

Human development according to the theory of positive disintegration includes five clearly distinguishable levels:

I. Primary integration

II. Unilevel disintegration

III. Multilevel disintegration: Spontaneous

IV. Multilevel disintegration: Organized or Directed

V. Secondary integration

The following description of each level may appear loose and diffuse, i.e. too clinical in character. However, this is necessary before one can show that behind this general and inchoate pool of features there are more structured factors at work. Therefore, a more rigorous definition of each level in terms of constellations of developmental factors will be provided in Chapter 5.

Primary Integration. The characteristic of cognitive and emotional structures and functions of primary integration is that they are automatic, impulsive, and rigid. Behavior is controlled by primitive drives and by externality. Intelligence neither controls nor transforms basic drives; it serves the ends determined by primitive drives. There is no inner conflict while external conflicts are the rule. The overall picture is of little differentiation, primitive drive structure, and predominant externality.

Unilevel Disintegration. It consists of disintegrative processes occurring as if on a single structural level. There is disintegration but no differentiation of levels of emotional or intellectual control. Unilevel disintegration begins with the loosening of the cohesive and rigid structure of primary integration. There is hesitation, doubt, ambivalence, increased sensitivity to internal stimuli, fluctuations of mood, excitations and depressions, vague feelings of disquietude, various forms of mental and psychosomatic disharmony. There is ambitendency of action, either changing from one direction to another, or being unable to decide which course to take and letting the decision fall to chance, or a whim of like or dislike. Thinking has a circular character of argument for argument’s sake. Externality is still quite strong. Nuclei of hierarchization may gradually appear weakly differentiating events in the external milieu and in the internal milieu but still there is continual vacillation between “pros” and “cons” with no clear direction out of the vicious circle. Internal conflicts are unilevel and often superficial. When they are severe and engage deeper emotional structures the individual often sees himself caught in a “no exit” situation. Severe mental disorders are associated with unilevel developmental structure.

Levels and Types of Development 19

Spontaneous Multilevel Disintegration. Its characteristic is an extensive differentiation of mental life. Internal experiential factors begin to control behavior more and more, wavering is replaced by a growing sense of “what ought to be” as opposed to “what is” in one’s personality structure. Internal conflicts are numerous and reflect a hierarchical organization of cognitive and emotional life: “what is” against “what ought to be.” Behavior is guided by an emerging autonomous, emotionally discovered, hierarchy of values and aims. Self-evaluation, reflection, intense moral conflicts, perception of the uniqueness of others, and existential anxiety are characteristic phenomena at this level of development. The individual searches not only for novelty of experience, but for something higher; he searches for ideal examples and models around him and in himself as well. He starts to feel a difference between what is higher and what is lower, marking the beginning of experience and perception of many levels. Critical awareness of oneself is being formed, and of others as well. There is awareness of one’s essence as it arises from one’s existence.

Spontaneous multilevel disintegration is a crucial period for positive, i.e. developmental transformations. The loosening and disintegration of the inner psychic milieu occurs at higher and lower strata at the same time. This means that the whole personality structure is affected by this process. The developmental factors (dynamisms) characteristic for spontaneous multilevel disintegration are described in Chapter 5. They reflect the nature of multilevel conflicts crucial to the progress of development: positive maladjustment, astonishment with oneself, feelings of shame and guilt, disquietude with oneself, feeling of inferiority toward oneself, and dissatisfaction with oneself, positive maladjustment.

Organized Multilevel Disintegration. Its main characteristics are conscious shaping and synthesis. At this level a person exhibits more tranquility, systematization and conscious transformation of his personality structure. While tensions and conflicts are not as strong as at the previous level, autonomy and internal hierarchy of values and aims are much stronger and much more clearly developed. The ideal of personality becomes more distinct and closer. There is a pronounced growth of empathy as one of the dominants of behavior and development.

The developmental factors (dynamisms) characteristic for organized multilevel disintegration are: subject-object in oneself, third factor (conscious discrimination and choice), inner psychic transformation, self-awareness, self-control, education-of-oneself and autopsychotherapy. Self-perfection plays a highly significant role.

Secondary Integration. This level marks a new organization and harmonization of personality. Disintegrative activities arise only in retrospection. Personality ideal is the dominant dynamism in close union with empathy, and the activation of the ideal. The relationship of “I” and “Thou” takes on the dimension of an absolute relationship on the level of transcendental empiricism. There is a need to transcend “verifiable,” “consensual” reality (known through sensory perception)

20 Theory and Description of Levels of Behavior

and to reach empirically through intuition, contemplation and ecstasy toward a transcendental reality. A balance develops between the philosophical orientations of essence and existence.

The developmental dynamisms characteristic of secondary integration are: responsibility, autonomy, authentism, and personality ideal. Those who achieve the level of secondary integration epitomize universal compassion and self-sacrifice. There are no internal conflicts at this level, in the sense of opposition between “what is” and “what ought to be.” The cognitive and emotional structures and functions are fused together into a harmonious and flexible whole.

TYPES OF DEVELOPMENT

The development of instinctive, emotional and intellectual functions can be ‘normal', one-sided, or universal (Dąbrowski, 1970). Multilevelness entailing a greater complexity of the inner psychic milieu, favors a more universal development, while unilevelness and integration favor ‘normal’ or one-sided development. Only within the context of multilevel development a high level of emotional and instinctive functions is possible. Thus, for instance, multilevel development leads away from primitive reactions of self-preservation manifested as needs for only economic, social, and institutional security to moral values and principles. For such a person moral values and principles are more important than security and material self-preservation. Similarly biologically controlled sexual behavior is replaced by depth of interpersonal relationships manifested as lasting and exclusive emotional ties. On a high level of development creative instinct becomes an instinct of self-perfection which besides the media of artistic expression begins to stress more and more strongly the concern for inner perfection.

The analysis of developmental patterns makes possible the distinction of the three types of development mentioned above. ‘Normal’ and one-sided development lack universality and the more potent multilevel developmental factors, and, therefore, do not reach the highest levels, i.e. organized multilevel disintegration and secondary integration (Dąbrowski, 1970).

1. ‘Normal’ development. By this we mean a type of development which is most common and which entails the least amount of inner conflict and of psychological transformation. Development is limited to the maturational stages of human life and to the innate psychological type of the individual.

The use of the term ‘normal’ is not fortunate here. It derives from the wide-spread and pernicious use of statistical standards as a basis for “normality.” There is no statistical normality in nature. Different forms of a gene are not more or less “normal,” they are only more or less viable, where the extreme is a lethal mutation in a gene, which nevertheless can be carried in the population. Similarly different isotopes of an element, i.e. atoms of an element possessing different

Levels and Types of Development 21

numbers of neutrons in the nucleus, are not more or less normal, they are only more or less frequent.

In developmental terms normality means an undistorted, i.e. free from accident, expression of developmental potential. If the developmental potential is limited, as for instance in mental retardation, such development must be considered normal in terms of the original endowment.

In the present discussion of types of development we have retained the use of the term ‘normal’ for historical reasons only.

2. One-sided development. Individuals endowed with special talents but lacking multilevel developmental potential realize their development mainly as a function of their ability and creativity. Such creativity, however, lacks universal components. Only some emotional and intellectual potentials develop very well while the rest remains undeveloped, in fact, it appears lacking. There is often disproportionate development of certain forms of expression of emotional, sensual, or imaginational overexcitability. It may be manifested for instance as excessive identification with others to the point of losing one’s identity but which lacks the more mature and balanced aspects of relationships, or as great fascination with the whole range of the world of real life or the dream or occult world but without any sense of discrimination. This may give rise to copious creative outpourings in writing, painting, movie making or scientific endeavor but it will lack the universal context of human experience, knowledge, and objective hierarchy of values.

One-sided development may also take a totally negative turn. This occurs in psychopathy and paranoia. In this case mental processes and structures are strongly “integrated” and resistant to environmental influence. Intelligence serves to manipulate objects in the environment, including, and foremost, other human beings. Combined with good or even great intelligence such integrated structure produces criminal leaders and dictators of whom Hitler and Stalin are the most tragic examples. They were characterized by a total absence of empathy, emotional coldness, unlimited ruthlessness and craving for power (Dąbrowski, 1970, p. 30).

3. Universal or accelerated development. When all essential cognitive and emotional functions develop with relatively equal intensity and with relatively equal rate then development manifests strong multilevel character.

The individual develops his potential simultaneously in intellectual, instinctive, emotional, aesthetic and moral areas. Such development manifests strong and multiple forms of overexcitability. But above all it distinctly manifests the individual’s awareness and conscious engagement in his own development. Here the autonomous developmental factors carry out the most extensive process of psychic transformation. Development proceeds fairly uniformly although not without intense crises, on a global front encompassing all functions and all dynamisms.

22 Theory and Description of Levels of Behavior

Comparing these three types of development we may say that both ‘normal’ and one-sided development proceed in conformity with the general maturational pattern of the human species of infancy, childhood, adolescence, maturity, aging and culminate in death. It is characterized by gradual psychobiological integration of functions. There is adjustment to external conditions of life, and conformity to a prevailing in a given culture pattern of professional, social, and sexual pursuits. Mental overexcitability and maladjustment appear only in specific phases of development, such as puberty and adolescence, or under stressful conditions, but disappear when the maturational phase or the stress pass. In this type of development we observe the prevalence of biological and social determination which gives it a fairly narrow and inflexible pattern.

In ‘normal’ development the level of intellectual functions is usually average, while emotional functions appear to some degree underdeveloped. In one-sided development intellectual functions may be superior, but emotional functions may still be underdeveloped, only a few of them are developed.

Accelerated development tends to transcend the general maturational pattern and exhibits some, or even a strong, degree of maladjustment to it. It is characterized by strong psychic overexcitability which give rise to nervousness, frequent disintegration of functions, psychoneuroses, social maladjustment. But with all this there is an accelerated global process of psychic transformation of cognitive and emotional structures and functions.

Accelerated development is an expression of developmental differentiation, certain degree of autonomy from biological laws, creativity of universal character, and transformation of the innate psychological type. Here we observe above average abilities in many areas, emotional richness and depth, and multiple and strong manifestations of psychic overexcitability. In individuals so endowed one may observe from childhood difficulties of adjustment, serious developmental crises, psychoneurotic processes, and tendency toward disintegration of lower levels of functioning and reaching toward higher levels of functioning. This however, does not occur without disturbances and disharmony with their external environment and within their internal environment. Feelings of “otherness” and strangeness are not uncommon. We find this in gifted children, creative and prominent personalities, men of genius, i.e. those who contribute new discoveries and new values, (Dąbrowski, 1970, pp. 29-30).

In summary, the description of the three types of development shows correspondence with the three general factors of development. ‘Normal’ and one-sided development are controlled primarily by the first two sets of factors, i.e. constitution and the environment. Autonomous factors, if present at all, are never strong enough to push development much beyond unilevel disintegration. Accelerated development is controlled primarily by the third, i.e. autonomous, set of factors. The stronger the autonomous factors the more resistant is development to the environment. This points to an important feature of accelerated development; it proceeds in opposition and conflict with the first and the second factor.

Levels and Types of Development 23

HIERARCHY OF LEVELS AS AN EVOLUTIONARY SCALE

The overall hierarchy of levels of integration and disintegration serves as a full evolutionary scale on which individual developmental sequences may be mapped. We argued that the most significant aspect of human development is emotional development because only in the area of emotional development the most extensive psychological transformations of behavior and personality are possible. Also we argued briefly that emotional development is unlike cognitive development, since it does not appear to follow an ontogenetic sequence. Rather, the changes in the organization of emotional structures and functions depend on the developmental potential which varies from individual to individual.

A strong developmental potential will manifest multilevel components already in childhood (Dąbrowski, 1972, p. 8). In consequence, the developmental sequence of a person so endowed from the start cannot be limited at any time totally to primary integration. One could say, of course, that the period of infancy is one of primary integration. However, we cannot at that time identify the developmental factors such as those we shall be concerned with here. By the time a child begins to speak in sentences we can attempt to discern developmental factors and establish whether the developmental trend is integrative or disintegrative. Perhaps it would be worthwhile to indicate that the neurological examination outlined in Part 2 does offer some suggestions for possible avenues of exploration of indicators of developmental potential in infancy.

A weak developmental potential will limit development to primary integration and unilevel disintegration. However, already, here, if potential for extensive unilevel disintegration is present it will manifest itself early, for instance in forms of psychosomatic lability (Dąbrowski, 1972). This means that if there is the potential to proceed beyond primary integration, then development can never be limited totally to primary integration because of the nuclei of disintegration which have to be present from the start.

The developmental sequences of positive disintegration are non-ontogenetic. They are measured in terms of levels attained in the course of development which has no distinct time schedule just as the process of evolution has no distinct time schedule. The levels of development are, therefore, a non-ontogenetic evolutionary scale. Any individual developmental pattern may cover part of this scale but none can cover the full extent of it (Piechowski, in press).

4

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF DEVELOPMENTAL EVOLUTION

THE ROLE AND THE NATURE OF CONFLICT IN DEVELOPMENT

The richer the developmental potential the more factors are brought into play which are in conflict with each other and the more disequilibrium is produced.

That disequilibrium may be a necessary dynamic of development is gradually being recognized (Piaget, 1967, Ch. 4, Langer, 1969), but there is still a long way to recognizing the developmental power of conflict. The nature and the extent of conflict as a developmental process has not been specified except for some aspects of cognitive development.

The position presented here is that a multilevel emotional conflict, or multilevel emotional-cognitive conflict is the sine qua non condition of development. Let us take, for example, the forms of overexcitability. Strong emotional and strong intellectual overexcitability lead to a powerful conflict between a personal, feeling and relationship-oriented intuitive approach to life and a probing, analytical, and logical approach. Inevitably the two will clash many times in the course of development before a resolution of the conflict is achieved. If strong imaginational overexcitability comes into play the conflict may spread even further. When sensual overexcitability enters the picture there arise conflicts between pleasure-orientation which even in its refined esthetic form touches only the surface of experience, and the more rigorous and profound demands of empathy, self-denial, moral principle and need for self-perfection. There may be a violent and enduring conflict between lower level needs of comfort and sensual satisfaction and the higher needs of reflection, solitude and attenuation of sensual desires which are now regarded as interference.

General Characteristics of Developmental Evolution 25

Others constellations, such as a mixture of extraversion and introversion, a mixture of schizothymic and cyclothymic tendencies, the opposition of automatic against deliberate behavior, are seeds of many conflicts. But at the same time, together with different forms of overexcitability they sooner or later become multilevel conflicts, i.e. conflicts between “what is” against “what ought to be.”